I. THE OLYMPIAN

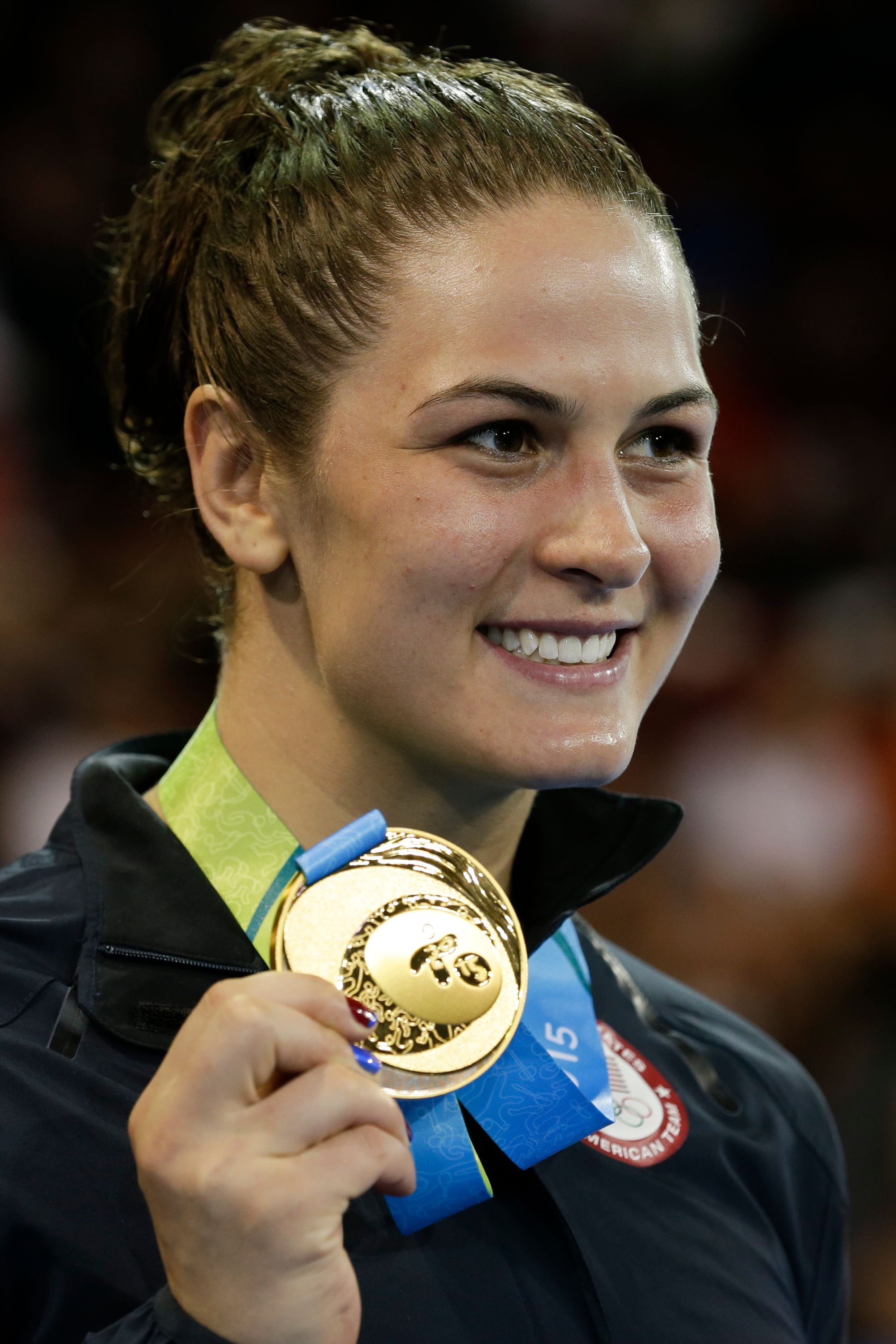

Adeline Gray stands near the top of the podium, an Olympic silver medal resting around her neck. One of the sport’s most dominant female wrestlers of all time has added another medal to her already impressive collection. But this one is special. She’s never won on this stage. And after all that she’s sacrificed the past five years to get here, for this very moment, well, any piece of Olympic hardware must feel like gold.

It wasn’t easy, of course. It never is when you’re an elite athlete at the top of your game competing against the best that the rest of the world has to offer — all during a worldwide pandemic, no less, that has postponed the Games, affected your training and halted your meticulous plans for starting a family.

So excuse her for a moment while she cheers from the Olympic podium in her white Team USA jumpsuit with a smile so happy that her face scrunches as she stares at her silver hardware. Because there was a time not so long ago that she contemplated walking away from it all.

“Wanted #graytogold but I’m coming home with #graytosilver,” she would later write on Instagram. “Proud of myself.”

She wasn’t finished, either.

Weeks later, Gray will go on to win a sixth world championship — another competition delayed by the pandemic, butting it right next to the Olympics. The annual event, which Gray calls a bigger event than the Olympics, takes place every year but an Olympic year, allowing the world’s best wrestlers an opportunity to compete at the highest level. If there was ever a silver lining for the 2021 Worlds, it’s that Gray was at her very best: mentally prepared and in Olympic shape. And with her victory, she cemented herself as one of the most decorated wrestlers of all time, regardless of gender or weight class, and reaching an echelon with the likes of Bruce Baumgartner, whose 13 World and Olympic medals are the most in men’s freestyle history, and Kristie Davis, who owns nine World medals.

Finally, after years of stress and anxiety and staring into the unknown, Gray could breathe and finally carry on with her next plan, the one she’d yearned for most. As she steps off the mat, her longtime trainer, Nate Engel, pulls her aside.

“It’s time to go be a mom,” he tells her.

II. THE WRESTLER

Wrestling has been a part of Gray’s life since she first took to the mat as a 6-year-old growing up in Colorado. She comes from a wrestling family — her mom’s side was heavily involved in the sport, her uncle coached, her dad wrestled in high school. She feels fortunate for her family for providing her with a path into a male-dominated sport. Gray was able to focus on improving and learning the intricacies at a time when girls elsewhere were forced to shave their heads just to compete.

Gray bonded with a cousin who became her built-in training partner. As her cousin, a boy in the same weight class, began wrestling other opponents, it opened a door for her to grow with him. By high school, she was winning the majority of her matches against boys, and coaches began to take notice. Around the same time, in 2004, the Summer Olympics recognized women’s freestyle wrestling as a sanctioned sport. As Gray says, “The stars were aligning.”

“I had this aha! moment that wrestling is really important to me. At that moment I realized I could do something special in this sport,” she says. “I wasn’t quite sure what that meant — looking back I wasn’t thinking about being a world champion; I definitely thought I could go on to college.”

After her junior year of high school, she moved to Michigan to train at the Olympic Education Center and immersed herself in wrestling. She switched styles from the folkstyle she competed in high school — a type of wrestling that focuses on control and execution — to freestyle that is used internationally.

“From day one of meeting her, you could see she was one of the hardest-working people in the room, both on and off the mat,” Engel says. Engel first met Gray at the Olympic Education Center in 2007 and says even in high school, “you knew that she was going to be special.”

Gray was named the high school wrestler of the year in 2009 and won a junior world title. She qualified for senior world teams and began traveling internationally. She had a plan — always a planner, that Adeline Gray — to commit four years to try and qualify for the 2012 Olympics in London. If she didn’t, she was going to move on with her life, go to college, retire as an athlete.

Gray found herself in a peculiar spot heading into the Olympic trials. The Olympic team only had four spots, and Gray was caught between two weight classes. Should she add weight and move up to 72kg (158 pounds), or drop weight and compete at 63kg (138 pounds)? She chose to drop weight, which left her exhausted. She failed to qualify. “Who knows what would have happened if I would have chosen to go up,” she says today. “Looking back, they were not the right choice. But I had my reasons back then.”

The disappointment hurt, but Gray was determined. She could do better. And she couldn’t see herself doing anything else with her life. Why would she when she had already dedicated so much to her sport? She went all in, eager to prove herself as one of the best wrestlers the sport had ever seen — and paving a path for future women to follow.

Terry Steiner, the head coach of Team USA wrestling, encouraged her to move up to 76kg (167.5 pounds). Gray obsessively lifted, trained with her younger sister, watched film, studied her opponents. She dominated at ground wrestling and developed a devastating leg lace that cripples opponents on the mat. Gray grabs their ankles and barrel rolls across the mat like an alligator devouring its prey — each spin earning her points, and enough spins can end the match. When her opponents developed a defense against her leg lace, she transitioned to an upper-body attack that left them questioning how they were supposed to defend her. Do they protect their arms? Their ankles? That’s the power of Adeline Gray: keeping her opponents guessing and having to make split-second decisions that can decide a match.

She won her first senior world championship in 2012 and then followed up with back-to-back wins in 2014 and 2015. By the time the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro arrive, Gray is the heavy favorite to take home gold.

That’s about that time she says she had a startling realization: when was she going to have a family? She was 25 at the time; her future husband, Damaris Sanders, four years older. If they were going to have children, she would have to be the one to sacrifice.

“Are you ready to start a family?” she asked him before the Olympics.

“I’m just waiting on you,” he told her.

Gray lost in the Olympic quarterfinals to Vasilisa Marzaliuk of Belarus, whom she had beaten in the past, and finished seventh overall. It’s a finish that felt like lightyears away from gold.

So, the ever-meticulous Gray and Damaris settled on a plan. She still had dreams of standing at the top of the Olympic podium. The Tokyo Olympics were four years away, in 2020. She would compete in Tokyo, they would get pregnant directly after, have a full year with their baby, she would have a full year of recovery, and she would train for two years for the 2024 Olympics.

If only it were that easy…

You know the story by now. A pandemic spread across the globe in early 2020, infecting millions and shuttering every aspect of life as we know it, months before the Games were set to begin in July. Gray, like Olympians throughout the world, was left wondering what was going to happen — would the Games even be held at all?

For Gray, the mounting stress and uncertainty were debilitating at times. Doubts flooded her mind in those early days as tears filled her nights. Would she be better off walking away from the sport altogether and starting her family? Damaris — one of her biggest supporters — encouraged her to push ahead and delay their plans for children. Geneva, her younger sister and training partner, pushed her during workouts and training sessions when Gray felt like she had nothing to give.

“It’s something she wanted so badly,” Geneva says. “She wanted to be a mom for such a long time.”

Finally, the International Olympic Committee announced the Games would be postponed for a year. The World Championships, it was later announced, would be held weeks after the Olympics. Not only could she compete for an Olympic gold, but go for a record sixth gold at Worlds.

But was it worth waiting another year — for gold, for children? She confided in her husband, her sister, her parents, her coaches, anyone who could help her navigate a fight that she had no training for.

III. THE MOM

It’s 3 o’clock in the afternoon when Gray’s face pops on my computer screen. Her braided brown hair falls over her shoulder onto her red USA t-shirt as her smile accentuates her high cheekbones.

She’s fresh off her 10th World Championships, where she placed third — her 10th medal to add to her illustrious career — and earned a berth in the finals of the Team USA Olympic trials this next April.

“My kids decided they wanted to take a nap a little early today,” she says. “That’s the first time they’ve done that.”

She has two kids. Twins, actually, who are about to turn 15 months: her boy, AD, and her girl, OJ, who they call Juice. And when she talks about them, her face beams brighter than when she stood on the Olympic podium. She’s learning to navigate this new life with twins and being a wife and an elite wrestler. Her family recently moved to California and she’s inundated with finding new doctors and setting up appointments and unpacking and training and getting enough sleep — for herself and her twins — and understanding her body postpartum.

She had a healthy pregnancy and carried her babies for 38 weeks. Both were born happy, healthy, bundles of joy who came home the next day. After waiting so long to have children, she freely admits she “would have had them sooner if I would have known how joyful and amazing they are.”

What’s striking about Gray, beyond the professional accolades, is how openly she discusses her life postpartum. She hopes by sharing her experiences that she can reach other moms who are learning to balance their new life after having kids.

She gained 52 pounds during pregnancy, she says, and after giving birth her large abdominal muscles separated, a condition known as diastasis recti. It’s a relatively common condition for women pregnant with twins; however, it led to complications with her postpartum training. She was hopeful to get back to training within six weeks; instead, it took six months before she even laced up her shoes.

Even once she was cleared to get back on the mat it wasn’t easy. She lost her pregnancy weight and came back 10 pounds lighter. She struggled to put on weight because she was breastfeeding. “I could not eat enough calories,” she says. She lost bone density during pregnancy. She couldn’t engage her abdominal muscles like before.

She turned heavily to her husband and a nanny, who allowed her to get the sleep she needed to recover — both from pregnancy and training. She’s made it a point to include her kids in every aspect of her career. Her Instagram is filled with photos of her and her twins at the gym, at home, or traveling overseas.

In between matches during the World Championship trials in June, Gray took time to breastfeed one of her twins in a foldable chair next to a concrete wall, her luggage, a pillow, and a mouthguard surrounding them.

“How many athletes do you see that in whatever sport they’re playing, they’re breastfeeding? It’s not talked about enough,” says Engel, her personal trainer. “That’s why she’s so unique because she’s doing all this hard work at such a high level while raising twins with her husband.”

At those World Championships in Serbia in November, where she placed third overall for her tenth senior-level medal, Gray posed for a picture with one of her twins — who happened to be chewing on mom’s bronze medal. Hey, kids will be kids.

It was an odd feeling for Gray. She had hoped to win and felt she could. In a past life, she would have spiraled after a loss — anger and sadness and disappointment all feeding one another into a self-deprecating tornado that would ultimately motivate her to the next match. That’s not to say she wasn’t sad, but when she held her twins all those bad feelings melted away. They didn’t care that Mama was sweaty or smelled funny or didn’t win. All that mattered was Mama was there with them. And that bronze thing around her neck — yeah, that looks like a good chew toy.

“This is by far the happiest I have ever been taking third. I wanted to win and I had faith that I could win. I can be the best in the world again. I feel dangerous knowing that I have the blueprint of how to win and I am willing and able to put the work in,” she would later post on Instagram. “I couldn't have done it without my amazing team of supporters. Thank you to my coaches, teammates, family, and friends for your unwavering belief in me. I am so grateful for your support every step of the way. This feels so special to have a great showing at the Sr. World Championships.”

“I’ve watched her win medals. I’ve seen her draw crowds to tears. I’ve seen her motivationally speak. I’ve seen her in every facet of her life,” says Geneva, Gray’s younger sister. “But watching her be a mom is my absolute favorite thing.”

Gray’s showing at this year’s World Championships qualified her for an automatic spot in the finals of the Olympic trials in April, increasing her chances for a shot at gold in Paris.

IV. WORLD CHANGER

Gray is now part of a second generation of women wrestlers that is inching closer to the end of their careers on the mat. She knows this and doesn’t shy away from the fact. Frankly, she’s proud of the path she’s paved for the next generation of women coming in behind her. It’s been 26 years since Gray first started, and so much has changed.

No longer does she hear the horror stories of young women who deal with boys who refuse to wrestle them or those who have to shave their heads to compete. “I don’t know if I would have been wrestling if someone would have told me I had to shave my head as a 16-year-old girl,” she says.

It’s all part of the nationwide growth of women’s wrestling since 2005, right around the time the Olympics welcomed women’s freestyle back into the Games. Like Gray says, “The stars aligned.”

Since 2005, participation in girls wrestling in high school has jumped from 4,975 participants to more than 28,000 in 2020, according to data collected by state high school associations and the National Wrestling Coaches Association. There are 25 states that have girls' wrestling championships, six of which have sanctioned the sport since 1998.

“Wrestling is a very unique sport. It is one of the toughest — if not the toughest — emotionally, physically and mentally on a young man or young woman,” says Brenan Jackson, assistant director of the Utah High School Activities Association. “There’s a core group of girls across the state who wanted to be challenged in those areas of life. They like the competition and physical exertion that wrestling provides. We were glad that we were able to offer these girls the opportunity to compete so that they could experience it, and even work toward earning college scholarships.”

That inclusion has opened the sport for athletes like Kennedy Blades, a 20-year-old who looked up to Gray, was once coached by Gray, and is now one of Gray’s toughest competitors. Blades was the one who beat Gray in the finals in her first tournament back postpartum.

As much as Gray has opened doors for women’s wrestling, she hopes her story also serves as an inspiration to moms worldwide: those who feel lost and tired and helpless and don’t know how or if or when they’ll ever get their lives back. She wants to see more resources for all moms that allow them to recover from a nine-month pregnancy, to get the sleep they need, and the mental well-being to be an attentive and caring parent.

“Women need to see that they can get their bodies strong again, they can trust their bodies, and they can still accomplish their goals,” Gray says.

There was a time she didn’t think she would come back to wrestling after having her twins. She had a decorated career and already gave so much to her sport. What left was there? Well, an Olympic medal, for one. Plus, a supportive husband whose encouragement pushed her back and to take over the world.

Gray stresses a good support system because she knows firsthand its importance. Without hers, she says, she never would have made it back to her elite level and Olympic aspirations.

She’s preparing for Paris in what may be her last Olympic games. She has to qualify first. The trials are in April, and she has an inside track after finishing third at this year’s World Championships.

For now, she’ll keep enjoying her babies — soaking in every precious moment and snuggle — while diligently training and following her blueprint to Paris that has served her so well for so long.

And anything beyond that, she says, “is just like icing on top” of a prestigious career.