You’ll have to forgive Ben Ritchie for a moment as he catches his breath and eases his racing mind. Since July he’s been traveling at what feels like a hundred miles an hour between countries and continents and speeding down mountain slopes. Now, for the first time this year, he’s getting a moment to breathe back home in Vermont, where winter is refusing to let go and the relentless rain saturates the ground with endless mud. It’s a far cry away from the snow-filled mountains throughout Europe.

This week in early April when he begins his offseason — his true offseason, when he doesn’t even have to think about skiing — is a bit jarring. For nine months of the year, he’s intensely focused on the next mountain, the next race, the weather conditions, his results, his World Cup standings, making slight improvements, getting to the next airport, rinse and repeat. And then suddenly … it stops.

So for the next two weeks at least, he’ll have dinners with his family, he’ll speed down the soggy trails on his dirt bike, jump on his mountain bike for a ride through the wet forests, or — simply put — live a normal life that’s rarely afforded to elite athletes.

Though it’s all a welcome reprieve for the 24-year-old Ritchie, one of the budding slalom stars for the U.S. Ski Team, it’s also a difficult time of year. How do you shut off your mind after months of giving your sport your all?

Ritchie is coming off his best season of his career: three top-10 finishes, five top 15s, a U.S. National Championship, and a personal best 17th-place finish in the World Cup standings — his best overall result in the world’s top international circuit for alpine skiing.

At the World Cup Finals in Sun Valley, Idaho, in March — Ritchie’s first finals appearance — he finished seventh overall after a stellar run to end his season.

The season closed on American soil, a point of pride for the skier from Vermont, but his pride stretched beyond his results. His family — mom, dad, older brother — and friends were in Idaho for the finals, which made his finish “super special.”

Ritchie is humble about his success. Yes, he’s proud of what he’s done. Yes, he might crack a slight smile in conversation. No, he’s not loud and boisterous and doesn’t like drawing attention to himself.

This, of course, is all part of his personality. He’s not a flashy guy who’s begging for attention. Just look at his Instagram — a social account he says he was forced to create — which features pictures and captions that are less focused on himself or his achievements and more on thanking those who have helped him find this success: his family and friends, sponsors, coaches and mentors.

After setting a personal-best finish in Idaho, Ritchie didn’t throw up his hands and yell and celebrate. He crossed the finish line, skied stoically to the fence, and soaked in the moment. Part of the reason, too, is because it took him a moment to process what exactly happened.

There are times when he skis that Ritchie blocks out the rest of the world — the fans, the cameras, the announcers, his opponents. His mind slows, his fear and anxieties and life’s stresses disappear, and for a moment, it’s just him and the mountain.

“It just takes you out of — all the things that don’t matter in life. You’re just in the moment, enjoying every bit of what you’re doing,” he says. “That’s the most addicting feeling for me.”

It’s no wonder that he’s a rising star for the U.S. Ski Team.

Ritchie’s talent has always been his raw speed. Whether he’s roaring down a mountain or soaring on his dirt bike, he relishes going fast. So of course he gravitated toward slalom, a discipline that requires speed and agility when racing down a mountain. Though skilled in speed, Ritchie had to learn the agility and consistency.

“The confidence, for me, really comes from my preparation. I’m someone who obsesses about the preparation, obsesses about the little things to improve on,” he says. “That’s not even just in skiing. If I’m working on my mountain bike or if I’m working on my dirt bike or playing an iPhone game, I’m super detail-oriented and meticulous — with everything I do.”

That’s a trait he gets from his dad, a recreational skier who worked full-time as an electrician and still found time to compete as a “high-level triathlete” and raced Ironmans.

Growing up, Ritchie watched his father wake up and swim at 4 a.m. before work, put in a full day’s work, then come home and hop on a bike or go for a run.

“Watching that, I saw that he was making the absolute most of his time,” Ritchie says. “He really instilled in me if you want to accomplish something, you might as well go all in.”

And then there’s Ritchie’s brother. Six years older. Bigger. Faster. Stronger. Ritchie couldn’t beat him at anything growing up. Not at basketball in the driveway. Not at football in the backyard. Not even at video games.

“He was always way better than me. And I was always fighting hard to try to beat him. But I never got discouraged by losing,” he says. “It really motivated me to try to beat him. I think that really built that inner drive and fire to attack and win.”

Despite all the losing, Ritchie owes his brother for helping him find his love for the slopes.

It came one of those winter weekends. The Ritchies’ home was near Jay Peak in Vermont, a resort tucked in the Green Mountains, where they’d ski regularly. His brother saw the slick jackets of a local ski club and begged their parents to let him join. They’d allow it only if he brought his little brother along. Frankly, Ritchie wasn’t interested, but his parents pushed him to go. By the end of the day, his brother was done with the slopes. But Ritchie — he couldn’t wait to get back.

Ritchie was an active kid growing up. He played basketball, football and lacrosse. He raced on his mountain bike. His family skied on weekends. Even as his brother beat him in just about every sport imaginable, he never gave up.

Beyond the local ski club, Ritchie’s parents never pushed him to ski. They never told him to work out or practice. If he was going to succeed, it’s because it’s what he wanted. While he enjoyed basketball and football and lacrosse, Ritchie knew even at 10 years old he wanted to be an Olympic skier.

It might have been different had he grown up playing basketball around stars like Kobe or LeBron. Instead, he spent his weekends on the slopes that were home to World Cup stars like Jimmy Cochran or Nolan Kasper or Tim and Robby Kelley. He’d get an autograph, maybe a quick chat, but it was more about being in their presence that drew him in.

By seventh grade, around the time he grew out of adolescence and into a teenager, Ritchie knew that if he was going to succeed in skiing, he’d have to give up those other sports and shift his focus to the slopes.

He enrolled at the Green Mountain Valley School in Vermont, a renowned ski academy that balances training with academics. GMVS was the best of both worlds for his family. Still so young, Ritchie wouldn’t have to move across country to train and study. The school was close enough that he would still be close to home near his parents, where he could flourish.

At school, Ritchie obsessed over his training, just like when he used to obsessively toss a lacrosse ball in his backyard for hours. Except now he was obsessing over workouts and technique in a way that stood out against the other students.

Remember how his older brother would beat him at everything? Turns out, when Ritchie competed against his own age — fueled by that fire and desire to win — he was really good. Good enough that his race results caught the eye of the U.S. Ski Team.

And once again, Ritchie found himself in a familiar spot: a young kid standing next to older, better, stronger giants. Eh, he was used to that by now, though. Although he was behind the learning curve, “They were all super friendly to me and welcoming,” he says. And unlike the beatdowns he endured by his brother, he accepted he wasn’t the best and soaked in every ounce of advice and wisdom the older, better skiers offered.

By tenth grade, Ritchie was on an upward trajectory that separated himself from others his age. He traded school in the winter for trips with the U.S. Ski Team.

“Ski racing on the road is unique where, you know, I live with my coaches and I live with my teammates that whole time. It’s not like basketball practice where I go to the gym and I see them for two hours and then go home,” he says. “We’ll train together, we’ll have dinner together, and we’ll hang out together. That helped me mature as a person really quickly. It was a lot of fun.

“And it helped me improve very, very quickly. I had a really good perception around what was going on. I knew I wasn’t the best and I wasn’t discouraged by that. I saw it as a chance to grow and get better. I knew that if I wanted to get better, there’s no one better than the guys who are older than me, more experienced, stronger than me. It pushed me in the best way possible and I absolutely loved it. That’s what I needed at the time.”

One of the best parts of his life, Ritchie says, is getting to travel the world competing in the sport he loves. One weekend he’s skiing in Sweden, flying down a mountain, immersing himself in the local culture, before flying to Switzerland and taking a small train up a spectacular mountain to a remote town. He’s skied all over America, Austria, Finland, Germany, France and Slovenia.

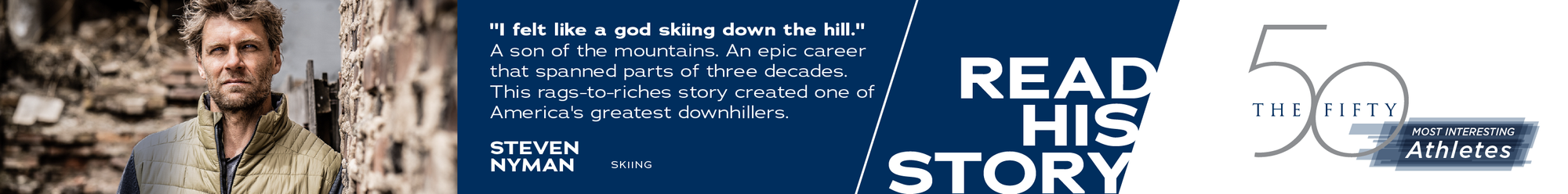

In 2019, he won a slalom silver medal in Italy at the World Junior Championships, his first true test on the world stage. In Bulgaria, two years later, he won gold at the world juniors, becoming the first American man to stand atop the podium in slalom since Steven Nyman in 2002.

Finally, he pieced it all together this season, thanks in large part to his coach, Tristan Glasse-Davies, and his technician, Ali Morton, both of whom joined the U.S. Ski Team this past season. Ritchie said they all instantly clicked — both in personality and ideas of how he can improve. The result, “A super positive environment to train in.”

It’s also a testament to his years of hard work he’s devoted to his sport, in trusting in the steep learning curve that comes with competing with the world’s best, in accepting that he needed more time and more years and more experience, in believing in his training and tweaks in technique and realization that speed doesn’t always breed success, and in maturing as a person and skier.

Although he’s just entering his offseason, Ritchie is already looking to the future — hoping to build off this season’s success by winning races, claiming World Cup titles. It’s also an Olympic year and an attempt to compete on the world’s biggest stage at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milano Cortina.

As it stands now, days into his offseason, Ritchie says he’s a long shot to represent the U.S. in Italy. But with an offseason to improve, a season of races to compete, and his dedication and drive for greatness, well, you shouldn’t count him out of anything.