Blake Horvath begins each day unlike pretty much any other college quarterback in the country. It starts at 6:45 in the morning, with the shouts of the plebes.

When Horvath enrolled at the Naval Academy, he was – like every other freshman – one of those plebes. He opened each day by bellowing to his fellow students about who was on patrol that morning, and what was for breakfast, and what the dress code was for that day. When you’re a plebe, you don’t round corners while walking down a hallway – you square your corners, taking each one at a 90-degree angle. And yes, Horvath is self-aware enough to know how goofy that might sound to an outsider.

“It’s hard to explain to people who haven’t been here and haven’t gone through it,” Horvath says. “It’s just so weird.”

But that’s the way it is in Annapolis. That’s the way it’s been for as long as anyone can remember. It took toward the end of Horvath’s freshman year before he began to fully understand why all these traditions existed, and why they mattered, and how they fit into the larger purpose of this place. But now he knows: There’s something to be said for the power of tradition in a world where everything feels like it’s constantly shifting and changing before our eyes.

I’m speaking to Horvath a few days before the Army-Navy game, which has always symbolized something bigger than football. But this year’s version feels especially poignant, not just because America itself feels like it's in a state of flux, but because college football has been changing so radically, too. For a couple of months this fall, both Army and Navy were undefeated; there appeared to be a real chance they could meet in the American Athletic Conference championship game and compete for a spot in the first-ever 12-team college football playoff.

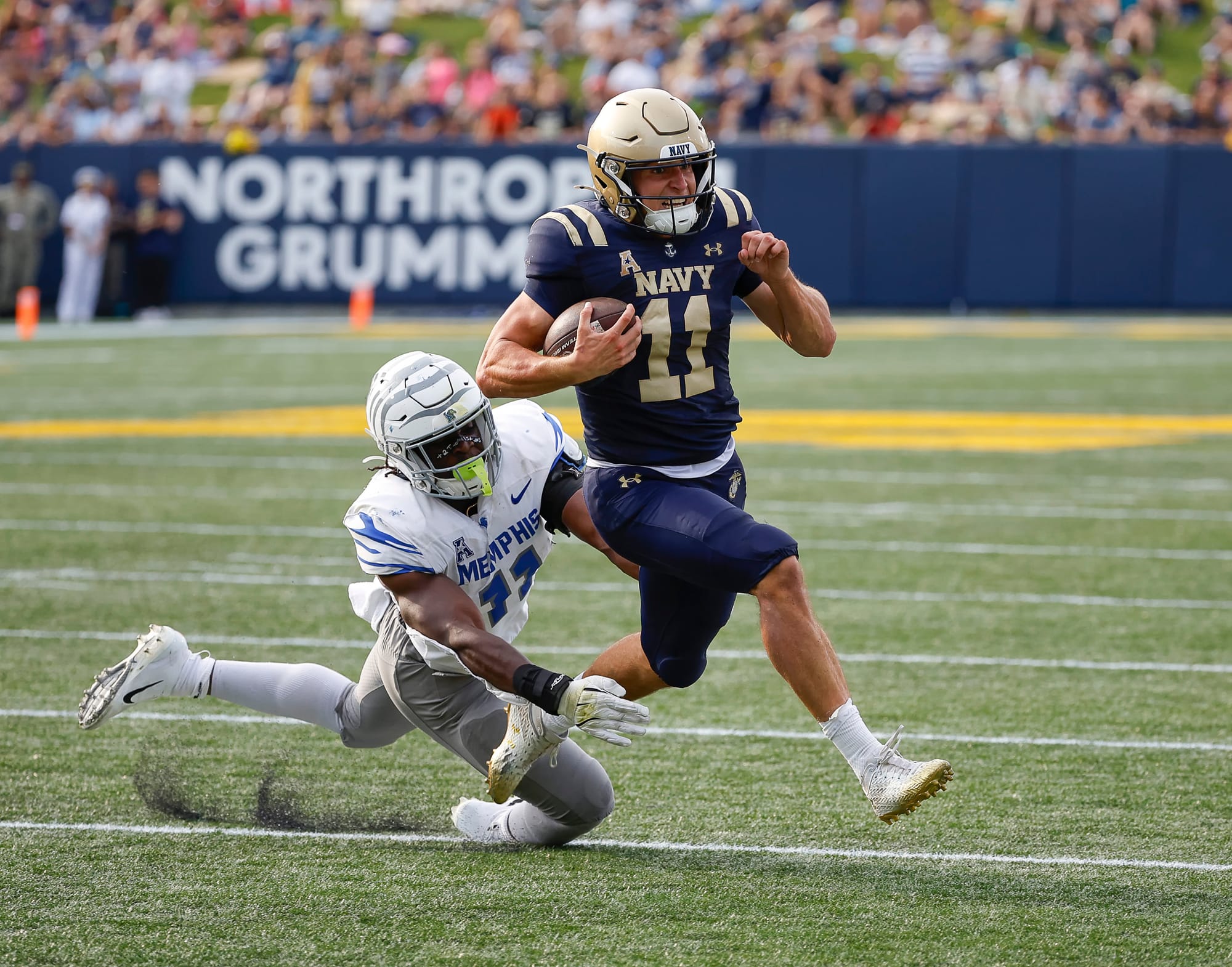

Horvath is a dual-threat for the Naval Academy. [AP photos]

It didn’t quite work out that way. Both teams lost games, and Horvath had to sit out a couple of games due to some nagging injuries. But Horvath still wound up having an extraordinary season, leading a prolific offense both by running the ball with ferocity and throwing the ball with remarkable precision.

Both Army and Navy had successful seasons while occupying a unique position: Along with fellow service academy Air Force, they are pretty much the only universities in major college football that haven’t chosen to join the sport’s modern arms race, paying their athletes through name, image and likeness collectives and declining to accept athletes who come to them through the transfer portal. In a lot of ways, their success – and Horvath’s success – serves as a testament to the power of tradition.

“I would say we’re almost a little naive to everything,” Horvath says. “If someone goes to our coaching staff and says, ‘How much money am I gonna get?’ None. You can’t. It’s just something maybe we take for granted, that we don’t have to deal with any of that.”

Before we dive into his backstory, I should probably inform you that Blake Horvath is a pretty unique dude. One of his coaches compared him to Mahoney, the unflappable lead character played by Steve Guttenberg in the Police Academy movies. Until I spoke to Horvath, I wasn’t quite sure I knew what he meant, but now I do. From the moment we start talking, it’s obvious: Here is a young man who’s entirely comfortable in his own skin.

And this is where I should probably tell you about the toy Horvath had stuck up his nose for seven years, because … well, because honestly, it’s just too good a story to leave out.

“I was six or seven, and I was playing with this little army barrel,” he says. He cringes for a moment at being forced to utter the word “army” just days before the Army-Navy game, but then he goes on …

Anyway, he was doing one of those dumb things kids do. He put the barrel up his nose and let it fall out. Did it again. And again. But then it didn’t come out. He tried to blow it out. Nothing.

He told no one. Not his mom. Not his dad. He was fine. He could breathe. He just went on with his life until he was 14, and he was in the pool, trying to drown his sister, like siblings do. And she retaliated by punching him in the face.

“Two days later, I’d had some congestion,” he says, “I felt something in my mouth, and I spit it out, and I’m like, ‘Holy crap, that’s the toy from seven years ago.’”

That story got repeated on an ESPN College Gameday segment, because how could it not? And I’m not sure what it symbolizes, if anything, but I guess it tells me that Blake Horvath is pretty comfortable with whatever happens – that he knows things will all fall into place when the time is right.

Which brings us to the backstory. Because Horvath kind of rolled with the punches here, too. In truth, he had the same dream that pretty much every kid growing up playing football in Ohio does: He wanted to go to Ohio State, and then to the NFL. At Hilliard Darby High School, he ran an option-heavy offense for his high school football team that was similar to what Navy ran. Some other schools offered him a shot to walk on at positions other than quarterback, but only one Football Bowl Subdivision school wanted him to play quarterback: Navy.

And at first, he thought, No way. “I’m not going there,” he told one of his high school coaches after they told him that Navy was interested.

But then Horvath thought about it some more. “In my mind, I’m like, ‘I’m not going to the NFL,’” he says. “That’s not happening. So what’s the best place to set me up for my future? It really came down to that.”

So he met with Navy’s defensive coordinator, P.J. Volker, who was in charge of recruiting Ohio. That piqued his interest, so he visited Annapolis, “and honestly, just fell in love with the place,” he says.

He didn’t play at all in 2022 and then played four games at quarterback in 2023 before a finger injury sidelined him for the rest of the season. He earned the starting quarterback job again heading into this season, and became one of the nation’s most efficient passers, right up there with quarterbacks at Oregon and Alabama and Ohio State. Those guys get more NIL money and perks than he ever will – when I ask Horvath what he hears from people he knows who play football at big-time universities, one of the first things he mentions is that he’s heard the Ohio State players get free Chipotle every week – but it seems unlikely that any of them could be happier with their choice of college than Horvath is.

“I look at my situation when I came in, and I was not a starting-level quarterback when I came in – that’s just the truth,” Horvath says. “But because I went to a program that develops players instead of going straight to the transfer portal, I’m able to get better every spring and fall and not have to worry about some guy coming in and getting paid $5 million.”

Instead, Horvath has one more season ahead of him while remaining in one of those most unique bubbles in college sports, a place where tradition still takes precedence over commerce.

The service academies do not offer NIL money. Instead, those like Horvath get an elite public-school education with job security attached. [AP photos]

This year, the Army-Navy game coincides with finals week, so after we get off the call, Horvath plans to start studying for his exams in a course called dynamic and stochastic modeling, and another in cyber-engineering. When Horvath graduates, he has visions of maybe becoming a pilot. He won’t be wealthy right away, but honestly, he doesn’t care that much about those things, because his time at the Naval Academy has given him a path toward a future that’s rife with possibilities, and a present that isn’t as fraught with complexities as the rest of college football. As one Navy coach put it, the NIL at their school is on the backend of things: A degree from one of the best public schools in the country and a guaranteed job in the service when you graduate. And for a lot of young people, that might be the better option.

As our conversation winds up, Horvath brings up the story of a quarterback at UNLV who left during the middle of the season because he claimed he didn’t receive the NIL money that he’d been promised.

“You don’t have to worry about that here,” he says. “You don’t have to worry about that at any military academy. And I think we’re lucky.”