Today, for Cade Hall, was something entirely new. Today, he found himself learning to remodel a bathroom. Other days he’s hanging drywall, or he’s demolishing concrete with a jackhammer, or he’s doing his favorite thing so far: Building out the wood frame of a brand new home. Most days, Hall returns home from his construction job near Irvine, California, utterly exhausted, as he learns the basics of construction, a profession that he’s still picking up day by day.

“I don’t know what you thought your direction would be coming out of college–” I say, and Hall cuts me off, mid-sentence.

“I thought I was going to be a football player,” he says. “And beyond that, I didn’t think about it much at all.”

Up until the moment he decided he was going to quit playing football, Hall built his life around football. He never really contemplated a future that didn’t include football, until he began to realize that was exactly the future he wanted. Hall majored in communications at San Jose State, in part because it fit well into a busy schedule of practices and workouts; when he was named the Mountain West Conference defensive player of the year in 2020, he began to think that he could play football for a living, just like his father had before him.

As his senior season at San Jose State arrived, Cade was considered likely to make an NFL roster. [AP photos]

Hall wasn’t wrong. He most likely could have played football for a living, or at least made a serious run at it. As Hall approached his final season at San Jose State in 2022, he had enough interest from scouts to think that he had a real shot at getting drafted or making an NFL roster as an undrafted free agent. “Pretty much everyone you talk to would say, why wouldn't you?” Hall tells me. “I mean, why wouldn't you just take that chance, if you have it? There's no reason not to.”

But by then, something had begun to shift in Hall’s mind. Football, the one thing that mattered most to him, started to matter less. And after his final season in college, he became that rarest of people: A legitimate NFL prospect who chose to walk away from the sport.

The reasons why are varied and complex, as Hall, 23, outlines to me over an hour-long video call from Southern California. But in order to understand why Cade Hall gave up football, and what it means – to understand why he chose to frame out an entirely new life for himself – maybe it’s best to start with the reason why Hall became so obsessed with football in the first place. Maybe it’s best to start with his father.

Rhett Hall graduated from Cal as a defensive lineman in 1991, nine years before his second son was born, and landed with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in the sixth round of the NFL draft. The Buccaneers cut him, brought him back, and cut him again. Five times over three seasons, the Bucs cut Hall, and he kept coming back. And as long as the opportunities were there, Rhett wasn’t going to let go.

“For me, I thought, ‘I'll do anything I can to keep going and play in the NFL and be a part of it,’” Rhett tells me over the phone from the Bay Area, where he works as a financial advisor. “And I'll keep going.”

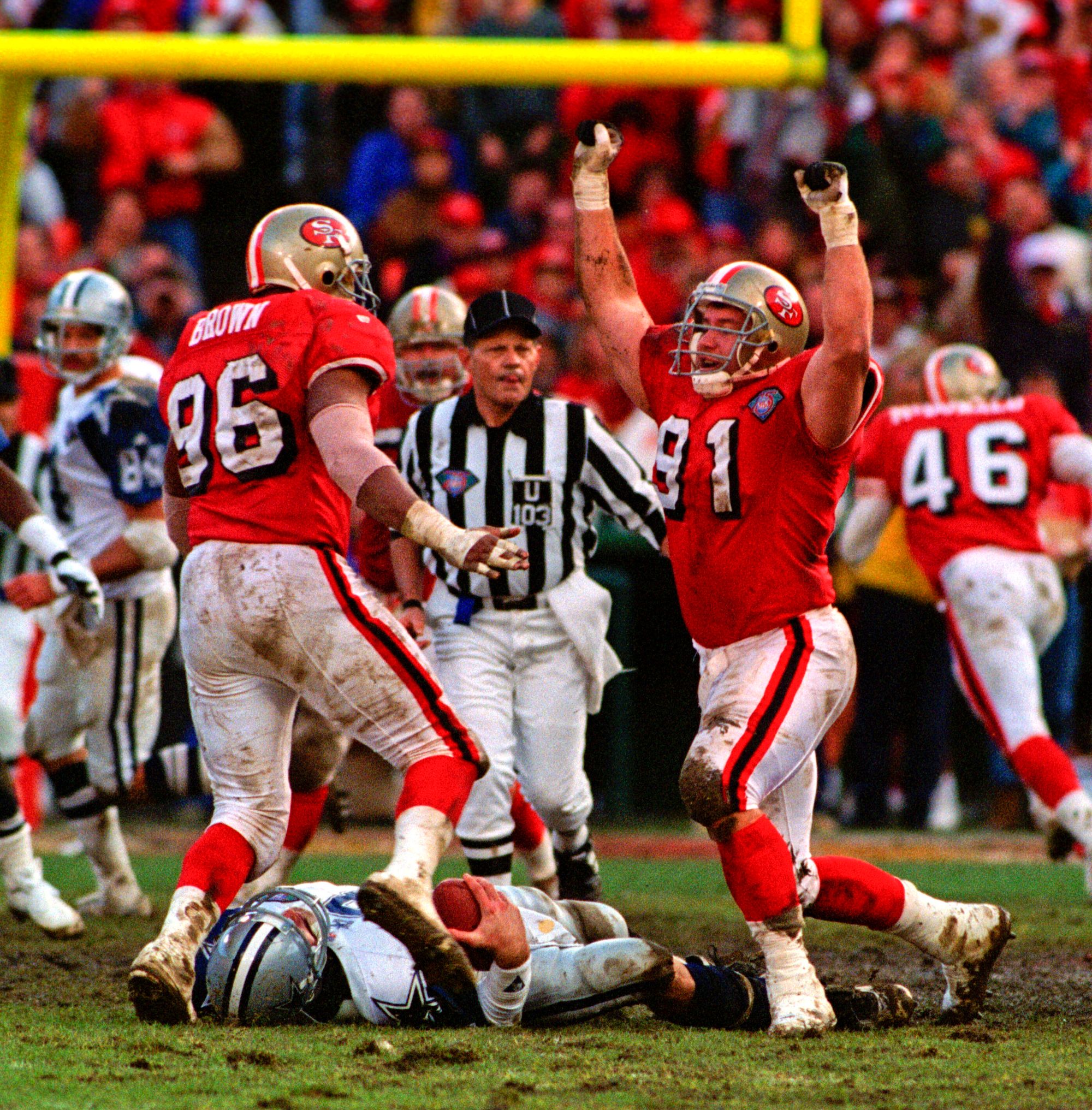

The end appeared to come in 1994 when the San Francisco 49ers waived him. Rhett started working in a friend’s stone and tile shop; he was fully prepared to let go of football, to move on to other things, but football pulled him back in again. The 49ers called and wanted him back. Rhett wound up sacking John Elway three times in a game. He sacked Troy Aikman twice in the playoffs and won a Super Bowl ring. After that season, he went to Philadelphia and played for three more years. But all that football took a toll on his body, including in 1995, when he suffered a pulmonary embolism during the preseason and missed most of the year. He’s not in terrible shape for an ex-NFL player, but his kids could see the toll it took, the nagging aches and pains that don’t go away.

“I think Cade saw it,” Rhett says. “I’ll be 55 in December, and I’ve had aches and surgeries, and Cade’s probably a lot more perceptive than I ever was, so he understood.”

Rhett made his sons wait until they were nine years old to start playing football, in part to avoid that toll too early on in life. But a current of athleticism ran in the family – Rhett’s wife, Juli, is a dedicated bodybuilder – and as Cade went through high school in Morgan Hill, near San Jose, he shaped his identity more and more around football, in part because he idolized his father.

Coming out of high school, Cade had only one scholarship offer – from San Jose State, where new coach Brent Brennan was trying to revive the program. But that one offer was enough to keep him going. “I was over the moon about it,” Cade says. “I felt like they were really taking a chance on me.”

Cade Hall was determined to make the most of that chance. He became a starter as a freshman in 2019 on a 1-11 team. And then in 2020 came the year that he thought had solidified his future, while simultaneously turning around the San Jose State program: He finished with 12 tackles for loss and 10 sacks as San Jose State went 7-1 during a pandemic-shortened season. He was named conference player of the year. He began to show up on the radar of NFL draft websites and scouts, largely because of the same relentlessness that had once prolonged his father’s career. A future in football became palpable.

And yet soon after, the doubts began to creep in.

First came the injuries. A conventional hernia surgery in March was meant to correct groin pain Cade was having, but it didn’t. He went to see doctor after doctor, in search of a solution, until a specialist diagnosed him with a sports hernia. It was a controversial diagnosis, Cade says, that some doctors told him wasn’t even a real thing. Cade had sports hernia surgery in June and barely practiced leading into the 2021 season. His body held up that year, but the pain still lingered. And Hall began to think about his future in a different way.

Cade traded football for his future. He's now learning how to build homes in Southern California. [AP photos]

Cade grew closer to his girlfriend’s father about his faith. He started attending church services. A couple of weeks into that 2021 season, he decided he was a believer himself. “I felt like I was letting myself down in a lot of areas of my life, and didn't feel like I was the person I wanted to be, especially with my wife,” Cade says. “I wasn't being honest with her about things. And it wasn't extremely severe stuff. It was kind of strange. Something just clicked and I was like, okay, I think I want to do this, and I want to try religion and see what God is all about.”

Meanwhile, Rhett Hall had begun to see hints creeping in during his regular conversations with his son. Cade would bring up the idea of leaving football behind after college, and Rhett began to challenge him on it.

“The fact that he brought it up with me says something, right?” Rhett Hall says. “I said, ‘If you were gung-ho on making it in the NFL, you wouldn't bring it up to me. My comment to him was just, ‘Think about why that’s happening.’”

One particular conversation with Rhett stood out to Cade. In the midst of their conversation, his father made a simple statement. I understand why you’d want to play pro football, he said. But I also understand why you wouldn’t want to play pro football. After all, Rhett understood what a grind it was to stay afloat in the NFL; he understood the sacrifices you had to make for your family, the uncertainty it entailed from year to year, and even week to week. It wasn’t something a lot of people talked about when they harbored those gauzy dreams about playing pro, but it was Rhett’s reality for eight years. And if Cade didn’t want that, it was O.K.

“No kid should be like, ‘Hey, dad, I’m gonna go play in the NFL for you,’” Rhett Hall says. “You have to have it inside of you.”

That single declaration from his father freed up Cade to begin re-evaluating his priorities. Cade realized he didn’t need football in order to define himself, and he didn’t need it in order to please his father, who just wanted his son to be happy. Football wasn’t make-or-break. Football was a choice, and if he chose to take a different path, it was not a reflection of his worth. “It was such an important milestone for me in my life that I felt like I had to reach so that I could prove I could do something great,” Cade says. “And then all that kind of went away as I got to know God. And I was able to make the decision if I wanted to do it rather than having it be such a no-brainer. I could look at it differently.”

As Cade’s senior season unfolded in 2022, he moved further and further toward the same conclusion. He was planning on getting married to his then-girlfriend, and as much as she supported him, he couldn’t help but wonder: Would it be fair to subject her to all that uncertainty, potentially for years to come? Would it be fair to be away from her, and to have no real financial certainty? And would he subject his body to a toll that would last a lifetime?

Days before San Jose State’s final home game against Hawaii last November, Cade made up his mind: When the season ended, he was done with football. He held off on telling his teammates and coaches, but his father knew. Late in the fourth quarter of that Hawaii game, with San Jose State up by 13, Hawaii faced a 4th-and-goal at the San Jose State 8-yard-line. One last gasp for Hawaii, and one last pass rush for Cade, who converged with teammate Viliani “Junior” Fehoko to sack Hawaii quarterback Brayden Schager. Cade looked up in the stands, found Rhett, and burst into tears.

Then Cade embraced Fehoko, who won Mountain West defensive player of the year in 2021, the season after Cade won it. At that point, Fehoko didn’t have any idea his friend was finished with football. But for Cade, there was a sense of finality to it. “It was like, ‘OK, we did it,’” he says now. “We left our mark on San Jose State. It was a really nice period on both of our careers.”

In April, Cade watched as Fehoko was drafted in the fourth round by the Dallas Cowboys. It was, he says, the only time in the past year that he’s felt even a twinge of something like regret. But it soon passed. Because this wasn’t what he wanted. And the challenge that lay ahead for Cade was to figure out what he did want. That search led him to take a job at the same stone and tile shop that his father had worked in years ago, after Rhett had been cut by the 49ers, when he was contemplating his own future without football. Working at the tile shop, Cade realized he enjoyed the work. And so in the exact same place, their futures diverged.

“I didn't ever step back really to look at it and go, ‘OK, where am I at, and do I really think I would have more enjoyment doing something else?’” Rhett tells me. “That never crossed my mind. It was just that I was doing what I was doing, and I kept doing it for as long as I could. But I one hundred percent respect Cade’s decision, and I admire it. I really do. Because I know I couldn’t have done it.”

There are, of course, a lot of lenses through which to view Hall’s decision to quit. A San Francisco Chronicle profile of Hall explored the notion of young athletes being more willing to walk away from football, as they recognize the toll it takes on their bodies, their lives, and potentially even their minds over the long term. Hall didn’t disagree at all with his story fitting into that angle. “I think it's good that all these conversations are happening and maybe that parents are considering not putting their kids in football, kind of like my story,” Hall says. “Just so it's not such a no-brainer. I think it's good to look at stuff a little more clearly.”

That’s perhaps what’s most remarkable about this story: That the father and the son are both so clear-eyed about it. That one of them couldn’t have imagined a life without football, and the other one has just begun to embrace a life without it.

The experience working in that tile shop led Cade Hall to apply for construction jobs soon after moving to Southern California to be closer to his wife’s family. He took a job with a small general contractor, and at least for now, the idea of a lifetime spent working with his hands doesn’t seem so bad at all.

In the meantime, he does the best he can to keep in touch with Fehoko, his old teammate. And to see him in a Cowboys uniform during the preseason? That was mind-blowing.

So I ask Cade: What if the Cowboys called you tomorrow? Would you be comfortable telling them, No thanks. I’m done?

He laughs. “Oh yeah, no doubt,” he says. “But the Cowboys wouldn’t want me to play.”

You never know, I tell him. After all, look at how his father’s career played out.

But it’s become clear at this point: Cade Hall is his own person now. And that makes his father far prouder than a career in pro football ever could have.

“Cade’s an exceptional person, man,” Rhett Hall says. “He really is super, super thoughtful about what he has going on in his world. All the feedback we get from him is that he's happy where he’s at, and he knows he made a good decision. The right decision for him. And I mean, that's awesome.”