His eyes are laser-focused as he stares down the 40-meter runway. It’s this moment that will determine everything. Will he be Christian Taylor, the four-time world record holder; or Christian Taylor, the man in second place?

After a series of jumps, the tall Taylor with his long legs and slender build, has a slight advantage over his fiercest opponent: Pedro Pichardo of Cuba, who, like Taylor, is one of the best triple jumpers in the world. And at these 2015 World Athletic Championships, they’re dueling for the crown to be named best in the world.

Taylor, the American from Georgia, sways on the clay-colored track, his eyes never wavering from the runway and the sandpit beyond. He raises his chiseled arms above his head and begins clapping…clap…clap…clap…clap…clap…clap…as the crowd joins in unison, cheering him on. With one last deep breath, he explodes down the track before hitting the board and launching into a…

Hop!

Skip!

Jump!

…as he sends himself soaring into the pit, his legs and feet nearly parallel to the ground as he tries to get every last centimeter out of his jump — because at this level, every centimeter counts — as he crashes into the soft sand below. It’s all over in 10 seconds and — oh my god, did he really just do that?

“That is absolutely huge,” an announcer calls. “It’s a massive, massive, massive jump.”

On his final jump, Taylor soars 18.21 meters — nearly the length of a bowling lane — to secure the world championship. It’s good enough for Taylor’s career best and the second-longest triple jump ever.

Taylor bows after exiting the pit. He finds his coach, Rana Reider, who wraps him in a hug. Taylor is beaming as he drapes the American flag around his shoulders and gives high fives to the roaring crowd.

But in the coming days, there’s a part of the jump that gnaws at him: he was a credit-card width short of the world record. How could he come so close and not break it?

“I was the happiest man in the world and the saddest at the same time,” Taylor recalls today. “I set an American record. I was a world champion. I couldn’t have dreamed for a better time for this to happen. But at the same time, I was just shy of the world record. It doesn’t feel like untouched territory because I’ve been right there.”

And so Christian Taylor got back to work.

It’s nighttime in Vienna, Austria, where Taylor now calls home. He’s two years removed from tearing his Achilles weeks before the 2021 Tokyo Games. At the time, Taylor was not only trying for a three-peat as an Olympian but seeking to break the world record on the world’s biggest stage.

At warm-ups during a meet before the Olympics, Taylor didn’t feel like himself. He didn’t have his usual power to hop! skip! jump! that had carried him to two Olympic golds and four world championships. As he hit the board during the competition, Taylor bailed out of his jump and jogged into the sandpit. He looked around confused. Had a judge hit him in the back of the leg during his run?

“That was the only thing that my brain could wrap around,” he says. “It was this sharp slap, like someone took a bat and was trying to hit a bug off the back of my leg.”

He walked to a medical tent where a trainer diagnosed a total Achilles rupture. At the hospital, Taylor was still in denial. Couldn’t he just get a shot that would allow his tendon to heal on its own?

He underwent surgery the next day.

He’s still unsure what happened. Like the rest of the world, Taylor’s life shut down with the COVID-19 pandemic. The facilities at which he trained had closed. Competitions had shuttered. The 2020 Tokyo Games were delayed a full year. Years of planning and preparation were gone. The pandemic felt like it came at the worst time for Taylor. He had just won his fourth world championship in 2019, which he calls the “perfect momentum builder going into the 2020 games.”

“I just felt like everything was in line,” he says. “I was going in defending my third Olympic gold. It felt like the winds were in my sails.”

Taylor spent the pandemic competing in occasional virtual events, which felt odd. Rather than competing on the same track, athletes worldwide competed through a series of live streams. It was common for Taylor to jump while athletes in Portugal, Switzerland, or the USA watched from behind their computer screens.

“It was so weird,” Taylor admits.

Finally, in 2021 when the world began reopening, Taylor was “full steam ahead” for Tokyo.

And then came the tear.

It wasn’t the first time Taylor would have to relearn triple jump. If he had done it once before, he figured, he could certainly do it again.

Taylor has always loved soccer. It’s only by chance he found his way into triple jump. Taylor ran with his middle school track team when his coach had a startling realization: the lean-and-tall Taylor was the only one on the team who could triple-jump into the pit. That was enough to at least win some points during competitions.

To fine-tune his skills, his coach told him to stand still before giving him a slight nudge. Taylor caught himself with his left leg. That was the leg that would power his jumps, his coach told him.

Taylor quickly fell in love with the sport. He was winning competitions in middle school and high school with his natural speed and talent for jumping. During one offseason, Taylor was practicing soccer when his parents approached him. He was too talented at triple jump to keep playing soccer, they told him, and if he wanted to go out of state for college, he’d have to find scholarship money.

“My parents said from the very beginning, ‘Whatever you do in life, strive to be the best. Don’t strive to be in the masses. Don’t strive to be mediocre,’” Taylor says.

He gave up soccer and joined his local AAU team. He focused all his attention on improving — running through his neighborhood with a parachute to increase his speed, intently studying VHS tapes to fine-tune his jumps. It wasn’t long before he started inching his way up the national ranks. He was named Georgia’s 2008 Gatorade Player of the Year. And then came the offer letters from Division I colleges: Georgia, Florida, Florida State, USC, Clemson, among a slew of others.

He chose the University of Florida, a decorated program with 14 NCAA championships, and doubled down on improving. As his friends partied and traveled, Taylor trained and competed and gave the sport his all.

“My dream was always to be the best in the world,” he says.

In three years with the Gators track and field team, Taylor won three national championships, eight Southeastern Conference titles, and was named a 10-time All-American.

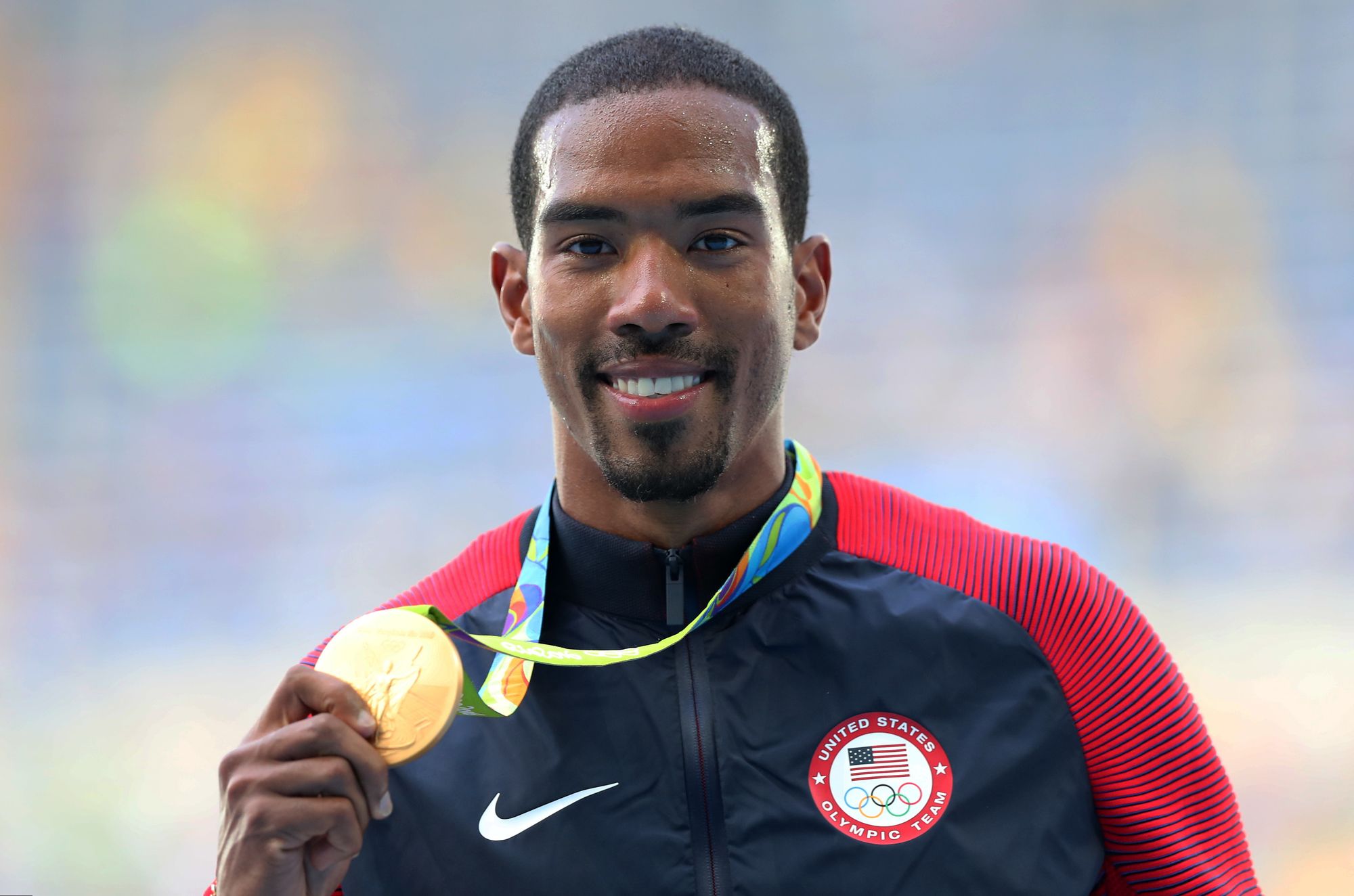

By the 2012 Olympic Games in London, Taylor, just 22, had established himself as one of the best triple jumpers in the world. And he proved it on an international stage when he won gold in the triple jump by soaring 17.81 meters (58 feet, 4 inches).

Even the best athletes aren’t immune to injuries. After years and thousands of jumps on his weak leg, each one absorbing nearly 15 times your body weight on impact, Taylor developed knee problems that began hampering his jumps. Four years earlier at Florida, his coach warned him he’d one day face these issues, but “I was 18 at the time and a know-it-all all.”

Now, if Taylor was going to continue to compete at an Olympic level — if he was going to have a chance at defending his gold medal in four years at Rio — he would have to switch jumping legs at the height of his career.

It would be like asking the best pitcher in Major League Baseball to switch pitching arms in the middle of their career.

It’s been a grueling two-year rehab for Taylor, who at 34, is finally feeling like himself again on the track. After his Achilles surgery, he had to relearn to walk, to jog, to explode down the runway and hop! skip! jump! into the sandpit. He’s still relearning the latter, trusting that the surgery was successful, and he can fully plant his leg and soar.

Through it all he never doubted he’d train hard enough to get back to an Olympic level.

“That was my mindset,” he says. “I’m already an Olympic champion, so that’s my bar. I can’t just participate now. With Tokyo being taken away, it felt like this isn’t how my story ends, so I’m trying to rewrite the saddest moment of my life so that it can be one of the greatest moments of my career.”

He had already done it after London. In those four years, Taylor worked from the most basic step — learning to jump off his right leg — to winning gold at Rio after jumping 17.86 meters (59 feet, 9 inches), besting his jump from London. He became the first athlete in the history of triple jump to win Olympic medals on both legs.

Now, he’s hoping for a third gold medal next year in Paris. This, he admits, will be his last. He’s nearing his middle 30s, married, and is ready to start a family. He’s sacrificed so much of his life for his sport. He’s spent years living abroad, missed birthdays and weddings and funerals, lost valuable time with his family.

But there is unfinished business. He wants to reclaim his gold medal he didn’t get to defend in Tokyo. And there’s Jonathan Edwards’ 18.29 meters (60 feet) world record still lingering at the top, so close that Taylor can nearly touch it.

“The thing that eats me up is the fact that I’m the second-best jumper of all time,” he says. “I’m not the world record holder; I’m two inches from the world record.”

After reinventing himself three times in his career, can he finally break the record in Paris before retiring?

“Do you know how many things I look at every day and think, ‘This is the difference between me and being the world record holder right now,’” he says.

He has less than a year before the Games begin next July. He’s rebuilding his strength and coordination, tapping back into years of muscle memory that carried him to the greatest heights. But there’s still so much unknown. The biggest question of all: After his Achilles tear, will he have to switch back to his left leg to give him the best chance to win in Paris?

If no triple jump athlete besides Taylor has ever won gold medals on both legs, does Taylor switching legs a second time and winning gold make him the best who ever competed?

That’s been Taylor’s motivation all along.

“Am I going to be remembered as somebody who had a good career, but …” Taylor says. “Or am I going to be remembered as somebody who had a good career, and…

“I don’t want people to say he had a great career, but the Achilles. I want people to say he had a great career, and he faced adversity and didn’t quit. That’s how I want to be remembered.”