There were moments in Paris when Courtney Ryan almost couldn’t believe what she was hearing… moments when the capacity crowd grew so unbelievably loud that she and her teammates couldn’t even communicate with each other in the huddle during a timeout… moments when they’d get back out onto the basketball court and the crowd would still be echoing in their ears.

This was what she had been dreaming of her whole life, ever since she was a kid playing soccer in San Diego and watching American women win gold in international competitions. Now, it was all happening; she was a member of Team USA, and she was playing for gold with her family and thousands of fans cheering her on. And if it wasn’t exactly the way she imagined, well, she’d long ago come to terms with that.

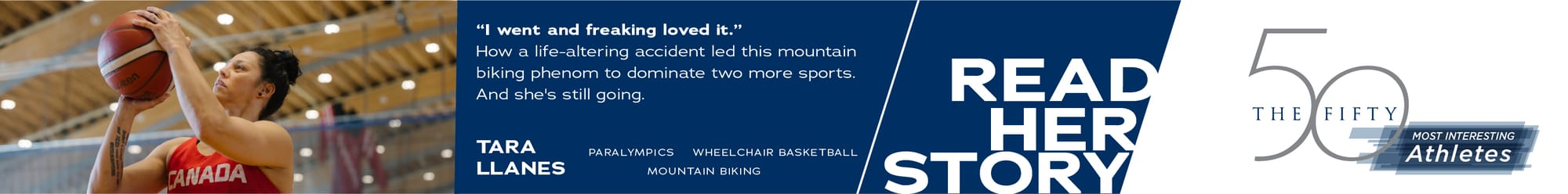

Her life had taken a tragic twist more than a decade earlier that threatened to undercut her entire identity as an athlete. But she was here now, a key member of the United States women's wheelchair basketball team at the 2024 Paralympics. She’d made it here playing another sport she’d come to love as much as she’d once loved soccer – a sport that had helped her rediscover her place in the world after a freak incident had led her to spend years coming to terms with her new reality.

And that new reality was kind of amazing: On the streets of Paris, people approached Ryan and her teammates and asked for selfies. “It was insane,” she says, “to be a part of that atmosphere.”

Ryan is back in Tucson, Arizona, having brought home a silver medal from Paris after the U.S. lost to a powerhouse Netherlands team in that gold-medal game. And what a year it’s been. The Paris trip came a few months after she and Team USA played an exhibition against a group of college all-stars at halftime of the NCAA Women’s Final Four in Cleveland – itself a paradigm-altering event thanks to the appearance of Iowa’s Caitlin Clark. Soon, Ryan, 34, will begin another season as an assistant coach for the University of Arizona’s women’s wheelchair basketball team, in a sport that’s starting to find more traction on college campuses with each season.

Every year, and with every experience, she continues to discover just how much perceptions are changing.

“I think women’s sports, through Caitlin Clark and that lens, has allowed the audience to focus on the athleticism, which is what we’ve been trying to speak on for years,” she says. “It’s not, ‘Oh, she’s good for a woman’ anymore. You hear, ‘She’s a baller.’ Point blank. Period. And seeing that evolution within the adaptive athletics community at the Paralympics was huge. Sell-out crowds, people coming up to you for photos – they’re seeing the athlete. Not the disability, not the gender. The athlete.”

Ryan grew up an athlete in an athletic family, an all-league soccer player at Coronado High School in San Diego whose sister played at UC San Diego. She wound up at Division II Metropolitan State University in Denver and was named a first-team All-American her sophomore year after setting a school record for a defender with 15 assists.

Early in her junior year, she woke up one morning with her legs feeling numb and tingly; she chalked it up to fatigue. In her next game, she made a run for the ball, got slide-tackled, and her legs gave out. A blood clot had worked its way into her spinal cord and burst, rendering her unable to walk. “I went from identifying as an athlete,” she says, “to not being sure what was going to happen with my future.”

Ryan spent the next few months in rehab back home in San Diego. A friend told her about a program called the Challenged Athletes Foundation, which sets up disabled athletes with mentors to help them find new pursuits. Ryan experimented with a number of adaptive sports; and then one day, as she and her sister entered a gym to observe a wheelchair basketball practice, she heard the banging and clashing of metal striking metal. She watched for a few minutes and immediately knew: Oh, yeah. This is it.

“Soccer is a very physical sport, and I loved that part of it,” she says. “So to see that physical nature through a different scope was something I really needed at that point in my life.”

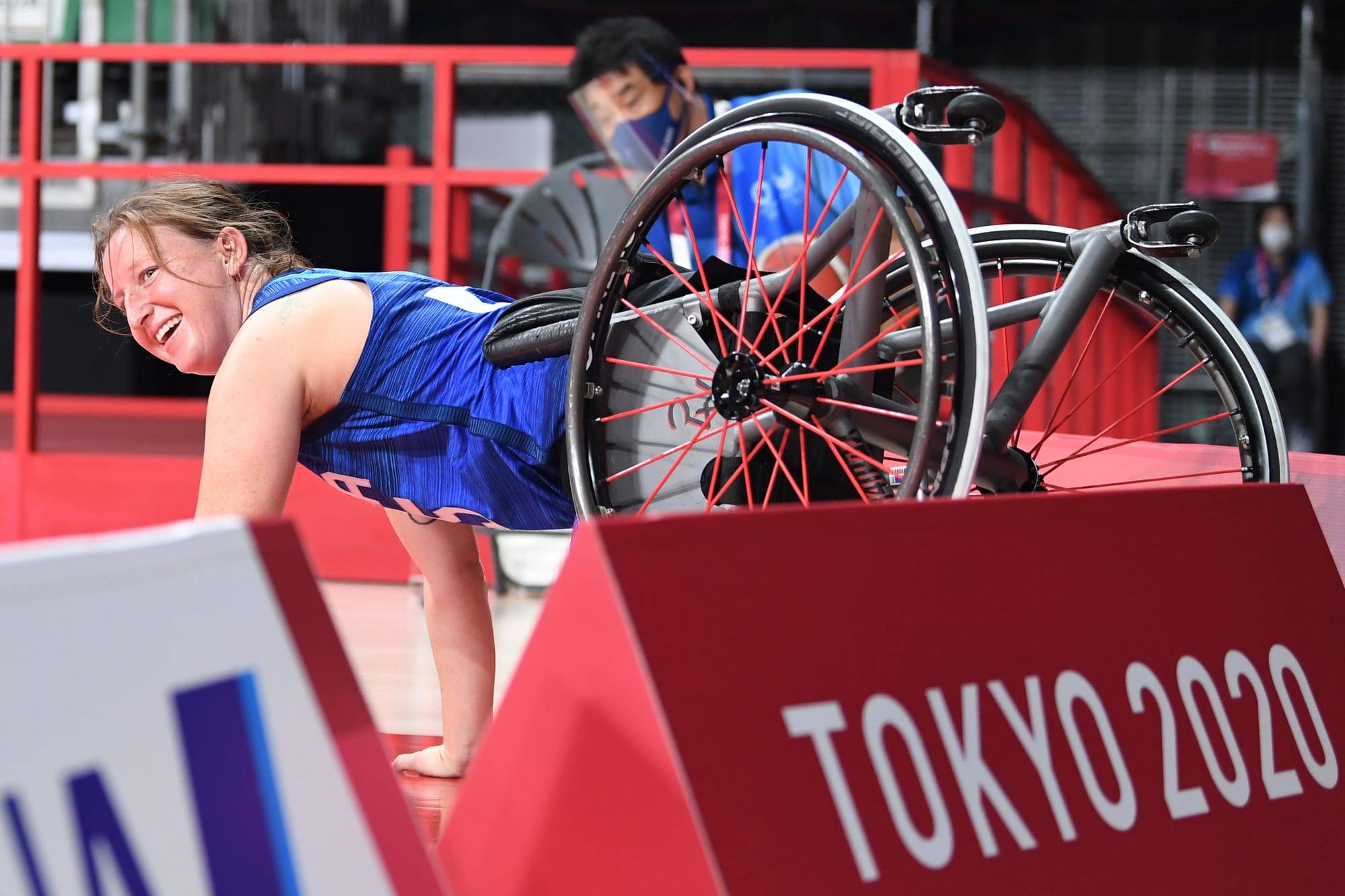

When she saw the physicality of wheelchair basketball, she knew the sport was something she'd love. [Courtesy photos]

Ryan entered a basketball tournament in Arizona. First game, five seconds left, her coach drew up a play. She set a pick and she made her way under the basket. The shooter missed a 3. The ball landed in Ryan’s arms. She hurled it with all the strength she had…and scored the game-winner.

Right there and then, while Ryan was celebrating her victory, that coach, Peter Hughes, sought out Ryan’s father, Kevin. He was, he told Kevin Ryan, going to offer his daughter a spot on the wheelchair women’s basketball team he coached at the University of Arizona.

“Hey,” Kevin told his daughter. “You just got a college offer.”

“I was like, ‘What’?” Courtney Ryan says. “I didn’t even know what he was talking about. I thought at that point in life that I was going to be living at home because I had stereotypical thoughts of disability.”

Over time, Ryan learned how to do more and more things that would boost her independence. On the court, she found her athletic identity again: She learned where to position herself, and learned how many similarities wheelchair basketball had with soccer. “Soccer is all about angles,” she says. “Where am I going to position myself between the goal and the opponent so that they don’t score? All of that easily translated into wheelchair basketball. What was hard was building upper-body strength.”

At first, Ryan barely even had the strength to hurl the ball upward for a layup. She started building up through swims and marathon gym sessions, and she practiced drills on YouTube from a Canadian man named Pat Anderson, widely considered one of the greatest wheelchair basketball players in the history of the sport. “I wanted to learn as quickly as possible,” she says.

Soon after arriving in Arizona, a teammate played in the 2012 Paralympics in London. Ryan joined a watch party with her teammates and found an entirely new goal for herself. If she couldn’t make it to the Olympics in soccer, why couldn’t she make it here? She talked to her coach about it the next day.

“You’ve got the potential to do it,” he told her.

“It brought tears to my eyes, knowing I could have the opportunity to wear that Team USA logo across my chest,” she says. “I was training that much harder, knowing that was an option now.”

Ryan attended Team USA tryouts in 2014; after she clipped one of the assistant coaches and knocked him out of his wheelchair and onto his back, she thought to herself, “That’s it. I’m getting cut.” But she didn’t get cut. She competed until her arms were so sore that she could barely move them. And she made the team.

The only problem? Mentally, she wasn’t ready yet. In order to be an elite-level athlete, she understood, you had to be completely focused on training. “I really needed to focus on this new life, and accepting that,” she says. “I still had a lot of misconceptions, a lot of stereotypical thoughts. Frustrations. It was a lot to cope with on top of the training load. I really just needed to fall more in love with the game, and fall in love with myself and with the trajectory of my life before I committed to that next step.”

Courtney Ryan has been part of the bronze and silver medal-winning teams in Tokyo and Paris. [Courtesy photo, left; AP photo, right]

So she walked away for several years. In 2019, she tried out for Team USA again. And made it again. She won a bronze medal in Tokyo in 2021. And three years later, in Paris, she topped that with a silver. In 2019, the same year she made the national team, she became an assistant coach at Arizona, which allowed her to help the next generation of athletes on that journey toward acceptance – and toward advocacy for a pursuit that’s only just begun to make its way into the mainstream.

Paris, in that way, felt like a step forward, all those fans cheering and asking for photos–although, she will admit, a few of them wanted to take pictures with her father, who’s gained a reputation for dressing up in an Uncle Sam costume at her games. “He’s also quite famous,” Ryan says with a laugh.

In a lot of ways, though, Ryan and her family really did take this journey together. She sees that now and knows that by exposing a new generation of young people to this sport, she’s educating children, their mothers and fathers, and brothers and sisters. “There are a lot of hardships when somebody has a child with a disability,” she says. “They're not sure what's going to happen. And then they discover this sport, and they just see this portal open for them.”

Michael Weinreb’s new Wondery Plus podcast, One Party Town, is available now on all podcast platforms.