Dixville, Liberia, West Africa - late 1990s

6° 22' 45" N, 10° 44' 41" W

As civil war grips the country, two young boys board a bus. They are brothers, they are toddlers, and they are told their destination would be safer for them. They would be further from the dangers of war — the nonstop gunfire, the explosions, the rampant death.

Liberians had been at war with each other since 1989. The first time lasted nearly eight years. The second lasted four, from 1999–2003. The root of such devastation is a familiar refrain: corruption, power, disparities among classes.

In total, the two wars counted 250,000 dead and millions displaced, many in refugee camps. Children were recruited as pint-sized merchants of death — if they were strong enough to hold a gun, they were given assault rifles and sent to the streets.

The brothers were too small for this fate. Instead, they would join countless other children hoping for a way out.

The bus was taking them to an orphanage in Dixville, about 7 miles as the crow flies from the capital of Monrovia. This, they were told, was the ticket to a better life.

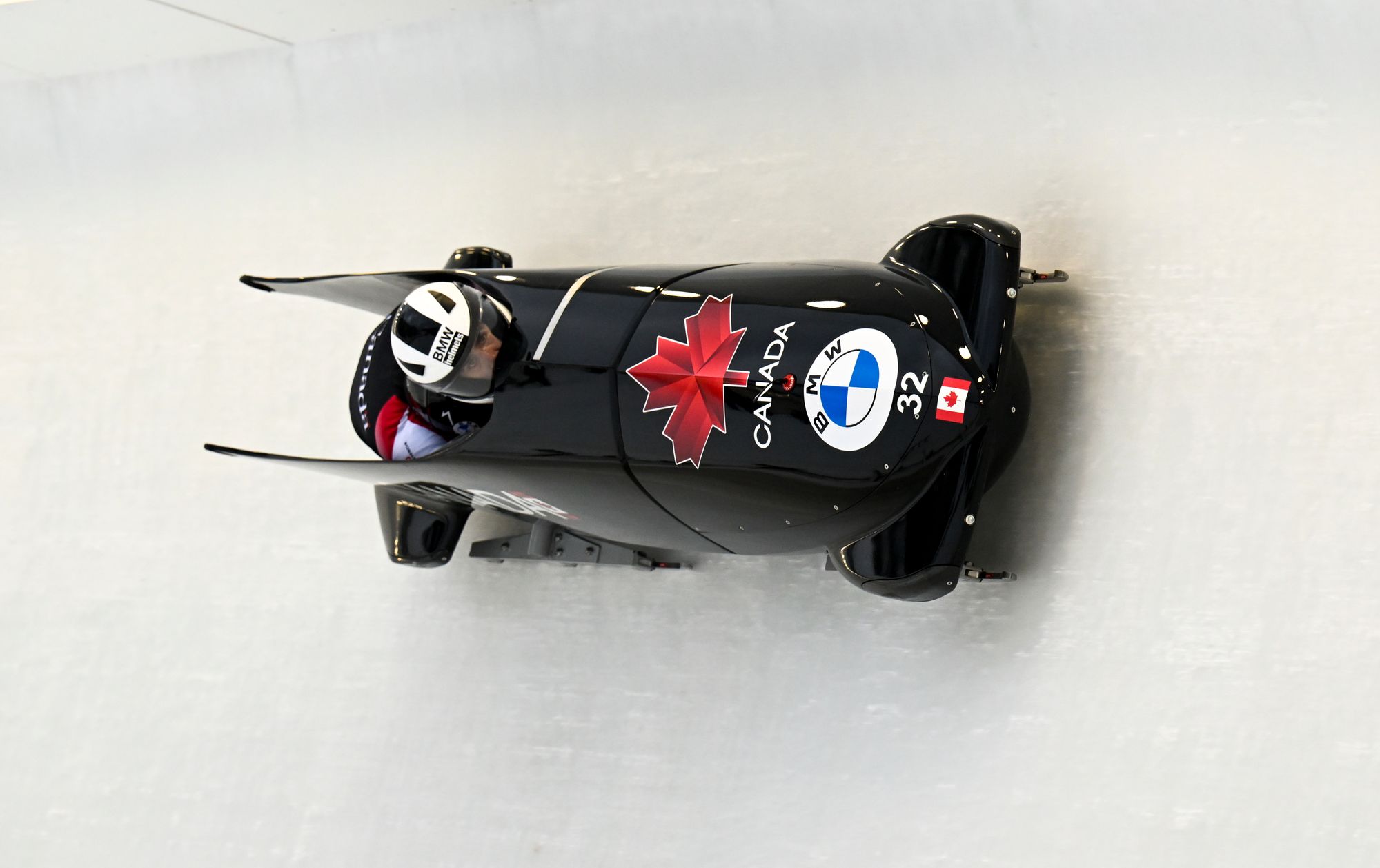

Cyrus has been determined his entire life. He's now focused on helping Canada reclaim Olympic glory. [Matthew Fults photos]

“The orphanage was sold to us as a better life, because all these kids would go there and then would get adopted from the United States and wherever,” the older brother says. “Who wouldn’t want to do that? Who wouldn’t want to live in an orphanage and eat and get adopted?”

Too young to comprehend much, they boarded that bus together bound for the unknown. They were uncertain what year it was. They were unsure how old they were. But they were together.

“I was the older brother,” he says. “I had to look out for him. I was trying to keep him as safe as I can. It was just the two of us, and it worked as a way to help each other get through that.”

Do you remember being on that bus?

“Not overly,” he says. “I just remember getting on the bus. But I don’t remember the bus ride too much.”

Here he searches for his words, starting and stopping his sentences. Thinking back, digging deep into a well of memories he has left unattended for many years.

“It wasn’t a happy time, I guess. It was a little bit sad. I was just hoping for the best.”

For a time, the war seemed distant. The brothers could still hear the sounds of savagery from afar, but “we were told not to worry about it because it wasn’t close to us.”

Until the war came to them.

He remembers a cease-fire.

He remembers the war starting again.

“And then they came,” he says, referring to the armed men. “They wanted to use the orphanage as a base. We were just a bunch of young kids. They were talking to the directors and we were just locked up in our dorms and had no idea what’s going on.”

The older brother remembers this: “We didn’t co-exist with them. They just kicked us out. They were like, ‘Well, if you don’t leave we’ll kill everybody.’

Where did you go?

“The organization that ran it had other homes. So we had to walk from ours all the way to that place. And it was like, I can’t even tell you,” he says, shaking his head. “I guess probably a couple of days, a couple of days of walking. I mean, we were a bunch of young kids just trying to gather everybody as much as possible and just … yeah …”

He remembers the adults out front, including the matron of the orphanage. He remembers them trying to keep the group — hundreds of them — together. There’s no telling which route they took. The landscape was flat, mostly dirt and clay. Thickets of trees and bushes scattered about. Nearby, a river.

“They were just kind of guiding us and trying to protect us from the people.”

His group was heading toward the capital, Monrovia. They walked for days. They slept outside, under the stars, exposed to the climate and the dangers of a violent unrest that canvassed the country. On this walk, the horrors of humanity were on full display.

“Yeah, it was very difficult to escape as you were walking for however long, a couple of days, and it’s like dead bodies right beside you, right?” he pauses here once more, searching for words that can convey the experiences of a young boy in that place and in that time. “So yeah, it’s really …” his voice trails off.

Dead bodies right beside you.

“Obviously, as a young kid, it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, it’s a dead body,’ but you have no concept. But, for some reason it doesn't faze you, you know? But yeah, definitely, definitely saw a lot of it and had no way of dealing with it. So it just kind of happened, you know?”

This march toward Monrovia eventually ended. He remembers being in another orphanage there. It was chaotic. He doesn’t remember how long they stayed, “but we were there quite a while.” After some time, the adults returned to Dixville to evaluate the situation. The armed men had abandoned the property, and eventually the kids returned.

They went back to the property with six dorms — three for girls, three for boys. Back to shared bunk beds, sleeping on the floor, eating one meal a day. Back to the routine of a makeshift school, playing soccer in the yard, dreaming. Back to no running water, a generator fueling unreliable electricity, and toilets that required buckets for flushing.

Back to waiting for a way out.

Two brothers, Cyrus and Alucious, still together. Time measured in shadow lengths; days turning over like pages in a book.

When would their chance to get out arrive?

Duncan, British Columbia, Canada - mid-2000s

48° 46' 43.2984'' N, 123° 42' 28.3068'' W

There’s an island west of Vancouver that carries the city’s name. It is treasured throughout all of Canada for its pristine beauty, its breathtaking coastline and its charming, fairytale-like towns. From mainland Canada, the island is accessed by ferry only.

Here, a young couple married in the ’90s and had three children by the time they turned 24. The mother says she can remember being curious about adoption when she was just 12. Somewhere, tucked away neatly in her soul of souls, was a welcoming heart for those in need.

“As we were raising our family, we had started going to church, we found faith, and we bought property and built this big house that we just thought would be perfect,” the mother says.

“All the kids finally had their own rooms and then once we built it, it felt like it was too much just for us.”

The mother says that through church, she received some “really radical Christian magazines.” One day, she found herself reading a story about Liberia. This was the spark that ignited an odyssey.

A typical training day for Cyrus is in the gym, and on the track. [Matthew Fults photos]

“It all kind of came together,” the mother says. “This big house that seemed like too much for us and this article about three organizations that were doing adoptions.

“And so I started petitioning my husband to adopt, and he was like, ‘No, no way.’ I said, ‘Okay, well, respectfully, I don't feel like it's your decision. I feel like maybe it's God's decision. So would you be willing to pray about it?’ And he said, literally, ‘Fine, pull the God card on me.’”

The father is described as sarcastic, with a dry sense of humor. So while he was needling her, he was also not in the same head space.

“So in the meantime,” the mother says, “we reached out to one of the organizations and they sent photos of children that were available for sponsorship. I said, ‘Can we just sponsor children and then if it works out, if we decide to move forward and if in the meantime they are adopted by someone else, that's great?’”

The mother says she prayed over the photos every day for a long time. They were hoping to sponsor one or more children with the idea that maybe they could adopt in the future.

In time, they were matched with two brothers and another boy. They immediately started writing letters to the boys and sending them things. The husband had an opportunity to travel with a family that had just reached the end of their process and they were bringing their child home. The experience changed his mind. He returned home to Canada and was on board with adoption.

“We just started the process very quickly and we got our home study done,” the mother says. “And on June 5, 2006, they were ours.”

The endeavor wasn’t over. It would take many more months of waiting on paperwork, medicals, visas and other red tape. The mother — as mothers do — took charge. In December 2006, she and her oldest daughter, who was 13, flew to Liberia to meet their new family members.

In Dixville, at the orphanage, the mother and daughter would witness the full spirit of the older brother, the protector, who was now 12.

“The first time I met Cyrus, he just came sprinting across the yard. Everyone was yelling at them that I was there, and he just didn't slow down. As this kid’s running closer to me, I thought, ‘Oh, take a step back. I might have a chance. But we are both going to go over backwards.’ He just flew into my arms. I didn't think he was ever going to let go.”

The mother and father, Crystal and Sean Gray, would complete their mission. Cyrus and Alucious arrived in their new country, Canada, on March 7, 2007. The next day, after a cold ferry ride from Vancouver, sister Madison was celebrating her birthday with a family of seven instead of five. The Gray family was now Mom and Dad, Ryley, Cyrus, Madison, Alucious and Kyler.

Calgary, Alberta, Canada - present day

51° 03' 0.40" N, -114° 05' 7.04" W

Cyrus Gray has been reluctant to talk about his journey. In fact, he shared that his teammates don’t know his whole story. He sees himself as a kid from Duncan, B.C., who, like Alucious, carved his own path. When you meet Cyrus, you understand this reluctance. He is low-key, polite, handsome and funny. He is your brother, your neighbor, your friend. He doesn’t want your pity.

In early September, I arrive at an address in the University Heights area of Calgary. It’s 10:28 a.m. and I knock on the door. Moments later, Cyrus cracks it open a quarter of the way, flashes his mega-watt smile and extends a hand.

“My car is out back,” he says. “Follow us there?”

The us is Cyrus and his girlfriend, Erica Voss. Both are members of the Canadian National Bobsleigh teams. We are headed to Canada Olympic Park (now known as Winsport), home of the 1988 Olympic Winter Games. There, Cyrus will spend the next six hours doing what he does: training to get better. He has already represented Canada in the Olympic Games once. But he’s on a new mission now.

Canada Olympic Park, now known as Winsport, has state-of-the-art facilities for athletes to train. [Matthew Fults photos]

As I sit in my rental, Cyrus wheels around the corner in a two-door, bright-red Honda. Erica waves from the passenger seat and we’re on our way. Within ten minutes, we are unloading cars and walking into the national team training center.

Cyrus is absolutely shredded. His traps are like twin cinder blocks mounted to his frame. He is lean, athletic and definitely looking the part at 6-foot–2, 211 pounds. Bobsledders often come from track or football. Think power and quick twitch. With this in mind, Cyrus looks a little small. Yet when you learn he came from college basketball, well, that’s just different.

When Cyrus and Alucious arrived in Canada in 2007, they experienced many firsts. Their first plane ride, cold weather, a ferry. They would get car sick because that was a new experience too. Cultural differences aside, they would be integrating into schools for the first time.

Liberia is heavily influenced by the United States. Just look at its flag. So the boys were able to speak some English already.

“Oh, man. Yeah, adapting to life here. It was … I don't know. I think school for sure was tough because my parents were still trying to figure out where we were at,” Cyrus says.

“So that was tough for me. And because we came close to the end of school year as well, right? So we just went to school for like a little bit and yeah, it was definitely an experience being in class before a lot of white kids.”

Cyrus started in grade 6 and began showing signs of being a quick learner, which he carries with him today. He managed to not only get caught up, but also to graduate on schedule in 2013.

Along the way, Cyrus and his brother were introduced to different sports. First, it was organized soccer around grade 7. Cyrus took to this quickly, earning the opportunity to play with grade 11 players. It was also around this time that he took an interest in basketball.

“One of my good friends, he was the one kid at school every lunchtime and before school and after school, he was in the gym playing basketball and I would go into the gym to watch him,” Cyrus says.

"I'm like, ‘Man, I want to be that good, you know?’ So I’ve told him to this day, it's because of him. I have the work ethic I do now because I was already behind in everything. So I had to dedicate all my extra hours to that. So it's like watching him do that, I said, ‘Okay, so he's doing the same thing. Why can't I?’”

As he dipped his toes into the basketball waters, Cyrus found the learning curve steep. His friends were playing at a level above his abilities at that time. Rather than pout or quit, he spent time watching, learning and applying what he was seeing.

That’s what I need to do to get better.

Work harder. Work smarter.

“So I did. Right before school. Lunch times. After school. To just be at their level. And then once I got to that level, it's like, okay, I want way more — to be better than them, right? And I just kind of carried that with me the whole way and ended up with the Athlete of the Year award in 2013.”

He turned that work ethic into his next opportunity, where he was a point guard for Camosun College in Victoria, B.C.

Cyrus arrives early and stays late. He's hungry for success. [Matthew Fults photos]

His mother, Crystal, saw this conviction when Cyrus was younger.

“I hike and backpack a lot, and sometimes when the going gets tough I tap into my inner Cyrus. There was a winter hike up a mountain here on the island,” Crystal recalls. “Cyrus is just like going.

“I asked him why he was going so fast. ‘Well, mom, why would you go slower?’ And he's like, ‘You just go faster. If you hate it, you just go faster and get it done faster so it's over. If you don't like it, you don't go slower and take longer to suffer.

“He just goes deep. And I think that's probably a good thing to have, but it probably wasn't from a good place that he developed it.”

Cyrus didn’t grow up with Olympic dreams. Too much of his mental currency was spent on surviving, looking after his brother, and longing for a family and a future. While he later starred in basketball, and admits dreaming of bigger things in that game, the Olympics weren’t on his radar.

“I just wanted to play basketball at the highest level. But I was never like, ‘Yeah, I want to go to the Olympics one day.’ Until I got into bobsledding.”

Until I got into bobsledding.

A few years ago, his mom and sister were watching an RBC Training Ground event, which is a series of evaluations where athletes sign up and get put through testing to gauge potential for Olympic sports. Those near the top move on to different rounds as a way to thin the herd. If you make it far enough, you may receive an invitation from a national team interested in your athletic feats.

With just eight World Cup starts under his belt, Cyrus already has a bronze medal. [AP photos]

His mom and sister told Cyrus, “You could be good at that.” At first, he wasn’t buying what his family was selling. But then, he learned they had already signed him up.

Challenge accepted.

“I went to the qualifiers and then got through that and then made it to the top 100. So then after that, they picked the top two athletes in the province and then they put you through more testing and then the sports teams from Canada come in to watch you.”

He drew interest from rugby and bobsled. Rugby was a quick and easy no. “I didn’t feel like getting hurt,” he laughs. When bobsled offered, he was initially hesitant, but agreed to visit Whistler, B.C., and see what’s what.

It almost ended as soon as it began. “They said, ‘Yeah, we’ll just sit you in and push you down and you’ll be good,” Cyrus recalls, noting that an experienced driver would be piloting the sled. “I’m like, ‘Okayyyyy.’

“My first time they made me push it. I almost fell and wasn’t able to get in.”

Things got better from there. Coaches saw enough in him to offer an opportunity. He received an invitation to a national team camp, and earned his way onto a developmental team.

“I was like, ‘Oh, this is something I can do.’ At the time, it was 2018 and people are on the road for the Olympics. I thought, ‘This is kind of cool. Maybe one day I can do all of this.’”

From there, he did what Cyrus does: he was determined to learn, to train, to get better every day.

He went deep.

Raw, skinny and unaccustomed to training twice a day, he discovered another level. He found mentors in more experienced athletes, including those with Olympic medals. He went where he needed to be — Ontario, Calgary, Whistler. He dialed back to his youth for answers, remembering the lessons from watching how hard his friend worked at basketball, then applied that ethos to bobsled.

Turning his basketball body into a power body has taken years in the gym. [Matthew Fults photos]

His reward was being named an alternate at the 2022 Beijing Olympic Games. He was there, in uniform, isolated with all the other athletes due to COVID. He had the maple leaf on his chest. He was representing Canada.

At those games, he didn’t compete. Canada won bronze. This was his new fuel. He wasn’t going to be satisfied. Yes, it was an impressive achievement to make the team. He was proud. But now he was also hooked.

“It was a no-brainer to keep going,” he says.

After the 2022 Games, Cyrus earned a spot on the top four-man sled as a push athlete. His team earned a World Cup bronze medal on the Whistler track. In 2023, he competed in the World Championships in both two-man and four-man, finishing 16th and 13th, respectively. He’s still raw, with just eight World Cup starts.

And then there’s this: With athletes retiring from the program (Canada has been a force in men’s and women’s bobsled for some time), the pipeline was looking thin. Funding was cut dramatically by the government. The next Winter Olympics is Milano-Cortina in 2026. There was practically a “Drivers Wanted” sign posted from Bobsleigh Canada.

“I was like, ‘Well, why not?’

Cyrus, as one would expect, has embraced this new opportunity wholly. He is learning to pilot two-man sleds and will spend this winter on the NorAm circuit, which is a level below World Cup. Here, he can get more runs, more races, more experience on tracks in Whistler, Park City, Utah and Lake Placid, New York.

His eyes are on 2026 for the experience of driving a sled at the Olympics, but his heart is set for 2030, where he expects to be in medal contention as a driver. He is determined. He is full of hope. It’s impossible to underestimate him, given his journey.

As our conversation at the national team training center comes to a close, I ask him what younger Cyrus would think of all this. The boy protector, the dreamer who sprinted into the arms of his adoptive mother.

In his soft-spoken way, he fidgets in his chair and flashes a shy smile. He shakes his head and rubs his hands together.

“I don’t even know what younger Cyrus would do. I’d just be amazed, you know. I’d be amazed and thankful for every situation. Tough times make tough people.”

As he continued to analyze the question, you can see how he shut off that part of his life. He identifies fully as Canadian. He’s still shaking his head, thinking of his younger self for what seems like the first time in a long time.

"I've never even thought of that, you know? What younger Cyrus would say … Yeah … yeah. But yeah …. Yeah ….” His mind is drifting now, perhaps trying to connect to the young boy who boarded a bus with his brother in the middle of a civil war.

“Oh, it turned out very well,” he says proudly. “I couldn’t have asked for better.”