The pangs of frostbite are still fresh after Dallas Seavey traversed nine days through the most desolate areas of the Alaskan wilderness.

“I’m molting,” he says, pointing out his shedding fingers. Beyond that, his energy levels haven’t recovered and he’s still re-acclimating to life back home. “You feel like you’ve recovered when you’re sitting around doing computer work, but then you go do something outside and start moving and your energy level is very shallow.”

Shedding skin, a lack of energy, nights spent sleeping on the frozen tundra: it’s a small price for the prize of claiming the most wins in the historic Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. The 1,000-mile race pits teams of man and dog against each other through the vast Alaskan landscape as Mother Nature unleashes whipping winds, blinding snow, and temperatures cold enough to freeze your bare skin in seconds.

It’s an environment where Seavey finds comfort in the most masochistic ways. That’s not saying it’s where he’s most comfortable, because who can find true comfort in a terrain where it’s fifty-seven degrees below zero with wind gusts up to ninety miles per hour as you try to navigate your way to the next checkpoint.

No, it’s here where he has invested years studying ice and snow, assembling trusted dog teams, and pushing himself that has driven him into the race’s annals.

He’s competed in 13 Iditarod races and his successes have largely gone unmatched. He’s finished in the top 10 in 11 races, a testament he attributes to his training and preparation. He holds the record as the youngest winner (age 25 in 2012). He won three straight races (2014-2016) and would have won four straight had it not been for his dad, Mitch, besting him in 2017 (Seavey finished second).

“It’s high stakes. We spend a lot of time, we spend a lot of energy. We spend a lot of other people’s time,” Seavey says. “And we get one race. We get one shot.”

Seavey is meticulous in his preparation in a way that could rival Tom Brady studying a defense or Tiger Woods reading a putt. His computer is filled with notes and spreadsheets of years past that detail situations and decisions that guide him for future races.

But being a six-time Iditarod champion, the most all time in the race’s 52-year history, Seavey knows that building a championship team is more about training and preparation than it is about the race.

And it all starts with the sled dogs, which, Seavey says, “are king of the endurance world.”

Seavey runs his own kennel, AK Sled Dog Tours, where he raises his dogs from puppies. He handles everything from feeding and veterinary programs down to understanding the smallest details of their genetics. What makes a great sled dog? Well, Seavey says, “You start with its base health. You’ve got to have a dog that has excellent nutrition. They’re ‘shining’ is a great way to say it. Their haircoat is perfect. They have to be both mentally and physically healthy. There are no external stressors. They can’t be worried about the angst of the dog next to them or any contention. They have to be completely trusting.”

Dallas and his dogs train about 4,000 miles through the Alaskan wilderness in preparation for the Iditarod. [AP photos]

While the race may run during a short window in early March, Seavey begins his training in August with about 20 dogs that hold the potential to earn a spot on the 16-dog Iditarod team.

Seavey spends these months on training runs examining everything from their teamwork to how they interact with each other, their demeanor, fitness, and—most importantly—their trust in each other and in Seavey at the helm.

The team is only as good as its weakest link, Seavey says, which is why they’ll train about 4,000 miles in various conditions. How does the team respond when in a blizzard with winds blowing sixty miles per hour? What happens when approaching a river crossing three feet deep and twenty feet across?

“Are they going to jump right into the water knowing that the dogs behind them are going to do the same thing?” he says. “Because I’ll tell you right now, if those leaders think that the two dogs behind them are going to slam on the brakes, there’s no way they’re going in first.”

Sometimes Seavey won’t finalize his roster until 48 hours before the race begins.

For all the work Seavey puts into training the dogs, he must also focus on himself. As the musher, he’s the quarterback of the team and must adapt and execute split-second decisions that can carry it to victory or doom it to defeat.

The foundation for those decisions is laid during the training runs. Standing in the back of the sled — where he spends a lot of time “watching dog butts” — he’s focusing on how the dogs interact, studying signs for when they’re tiring, and calculating thousands of scenarios of what might happen on the course. Seavey isn’t one for surprises, so he distills those months of knowledge gathering into a game plan for the race.

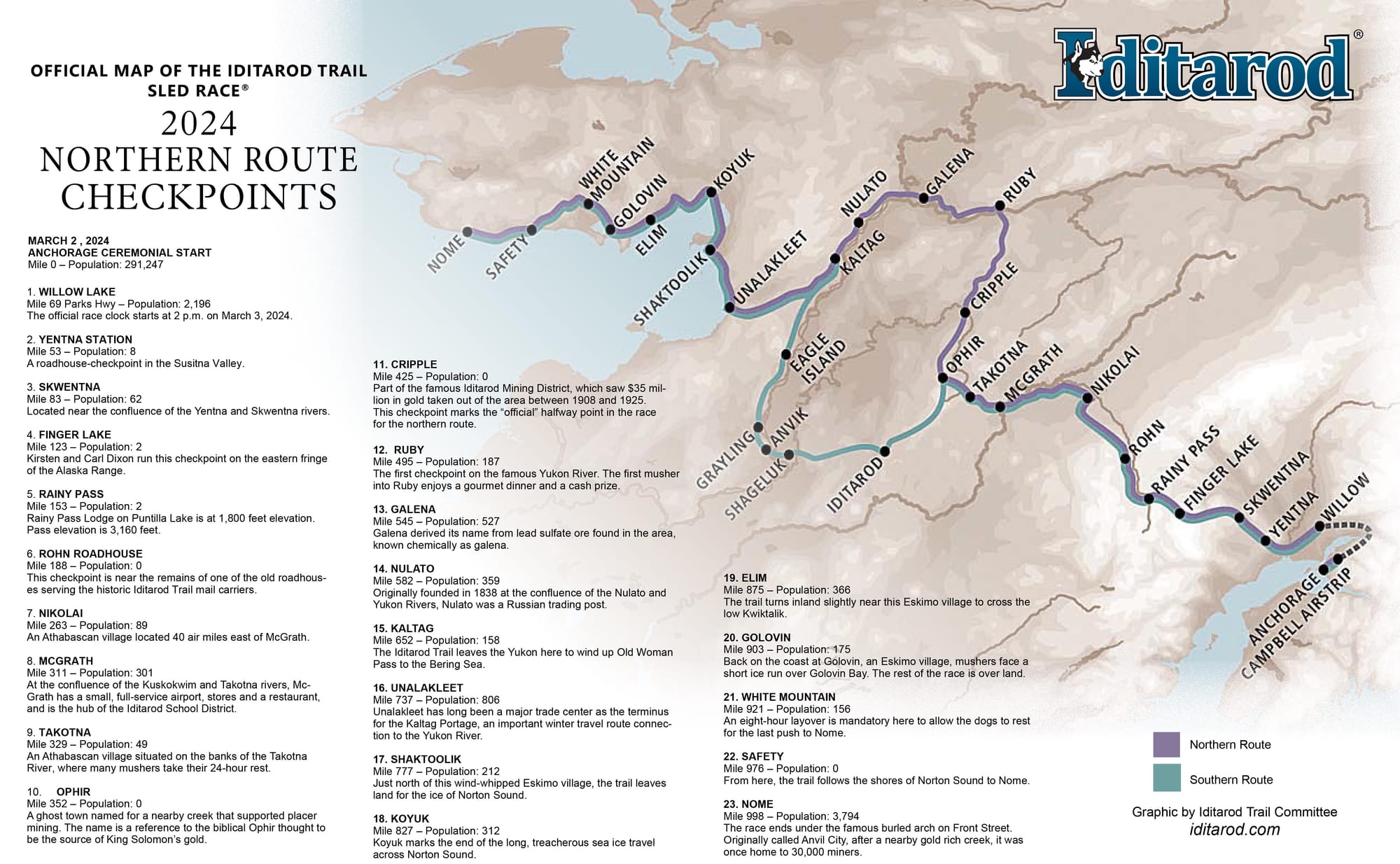

The Iditarod runs from Anchorage in the south to Nome in the northwestern tip of the North Pacific Ocean. The route runs between 975 to 1,000 miles, depending on the year (the race swaps between a northern and southern route each year), with either 25 or 26 checkpoints positioned throughout.

One of Seavey’s strengths is being comfortable in the uncomfortable, a side effect of spending hundreds of hours in cold Alaskan nothingness. He often views those checkpoints more as a resupply station than a rest stop. So when he sees his team tiring in a remote section far away from the next stop, he’s happy to set up camp and let his dogs eat and sleep. As he says, “If I can recognize that and add 15 minutes of rest now, I only lose 15 minutes. If I don’t notice until tomorrow, I may lose two hours to get them back to the same stamina. And if I don’t notice it until the next day, I may lose six hours.”

It's a mistake he’s witnessed too often in a race. Mushers, especially young ones, want to get out to an early lead and push their teams harder. Seavey knows that the race is won in the final 350 miles, where “the chinks in the armor start showing.” Like a game of chess, racing an Iditarod is a delicate balance of rest and running. And for Seavey, “I like playing the chess game when I haven’t slept in eight days.”

Anything can happen in nowhere Alaska.

One moment you’re skating along a frozen lake when the ice gives way and you find yourself up to your knees in the frigid water with a team of dogs up their chests.

You might find yourself traveling along the coastline of the Bering Sea in a wide-open ice land with ninety-mile-per-hour wind gusts pushing you closer to the dark water with no one around to hear your screams.

Or you may be taking a blind turn, like Seavey was during this year’s race, when a moose attacks your sled, marring one of your dogs, and forcing you to shoot and gut the moose right there.

“Dallas has proven his ability to overcome adversity on multiple occasions,” Iditarod CEO Rob Urbach said after Seavey’s latest victory. “This historic win is the embodiment of his professionalism, strength and full exemplary dog care.”

There isn’t much Seavey hasn’t seen in a race in the 30-plus years he’s been involved in training and racing dogs. He grew up on a ranch in Alaska that doubled as a kennel. His dad, Mitch, is the first in the Seavey family to make racing his full-time job. Like his son, Mitch followed in his father’s footsteps, Dan, who played an integral part in staging the first race in 1973, where he finished third.

“Running the Iditarod,” Mitch says, “is a family tradition.”

Ironically, after Seavey set the record for the youngest winner in 2012, Mitch set the record for the oldest winner in 2013.

While Seavey says the two have a close relationship off the course, they’re bitter rivals during the race. They don’t discuss training, Seavey doesn’t share modifications he makes to his sled, nor do they strategize moves that can cut time.

During the 2016 race, Seavey says Mitch had a sizable lead with a seventy percent chance of winning the race. But because of some “unique stuff schedule-wise and some positioning,” Seavey passed Mitch during one of the last checkpoints to win the race.

“It was really tough because my plan worked perfectly,” Seavey says. “At the same time, it was heartbreaking for him because he was sure he had it in the bag. And all of a sudden what I had been slowly developing over three days slammed it shut on him.

“I remember leaving the checkpoint and I should have been ecstatic. We were actually going to pull off a victory! But, you know, it’s my dad and I care about him. And I was literally crying leaving that checkpoint. I felt so bad for him. But I will say when you don’t sleep for nine days, you’re very emotionally vulnerable. You feel everything very acutely.”

It’s August now, about time for Seavey to start preparing for next year’s race. He’s already reached the upper echelon of his sport as he prepares for a possible seventh victory. What more is there to accomplish?

There are new dogs to train that are vying for a spot on the team. There are countless expeditions into the wilderness where they’ll learn about trust. They’ll brave the cold and find comfort in the most uncomfortable situations.

It’s in these moments where champions are built.

There’s much work to be done for one race, for one shot.

The pangs of frostbite be damned.

Advertising and sponsorship opportunities are available. Contact Jim Hoos at jhoos@r1s1sports.com or 602-525-1363.