Want the story behind the stories? Join our newsletter for bits and bites you won’t get elsewhere.

On a crisp fall morning, U.S. Naval Academy midshipman Dan Cnossen went for his morning jog. He was a senior, and being an upperclassman allowed him privileges, like running outside the yard. He was just weeks into his first semester of that final year. With no early morning classes, he often ran, looking to stay fit and keep his mind clear.

At that time, regulations were a little looser than they’d be in just a matter of hours. He was running without his military identification card. He didn’t have a cell phone.

When he returned to the yard, the gate guard seemed agitated and approached Dan with a sense of urgency.

“Where’s your ID?” the guard demanded.

Dan didn’t have it. That wasn’t previously required.

He managed to talk his way inside the yard and was suddenly aware that something was amiss.

“But I didn't know what — I didn’t have a cell phone or anything like that back then. And I went back, changed, went to my first class, and they had the television on with the news. And we saw everything happening,” he recalls today.

The date was September 11, 2001.

For a land-locked kid from Kansas, the Naval Academy was a huge honor. Soon, he would find himself at the tip of the spear in a war without borders, and without end.

Two-hundred acres on the outskirts of Topeka nurtured a young Dan Cnossen and offered a playground for his imagination to conquer. His family roots there extend to the late 1800s when his ancestors moved from Ohio to build a new life on the prairie thanks to the Homestead Act.

He was raised with an appreciation for the land and the work that goes with it. He loved exploring the outdoors, the wooded areas on his family’s farm, playing hide-and-seek with his sister, and shooting tin cans with a BB gun.

Dan’s father wielded a quiet influence over his son. He was a Marine Corps veteran, serving three years in Vietnam. He never put pressure on Dan to pursue a career in the military. Instead, through a stoicism reinforced by a love of country and honest work, Dan absorbed and embraced these heartland-level values.

In addition to his well-crafted adventures running around on the farm, Dan played sports.

“I wasn’t a standout athlete, but I played team sports, and those team sports weren’t really my calling as an athlete. But you learn a lot from team sports, and I think that transferred over to the military.”

Dan says his father’s service, coupled with books he had read and the military’s marketing machine — Hollywood — fueled his passion.

“I wanted to be part of a team and continue being an athlete, but in a different way. And I wanted to serve the country.”

With sights on the Marine Corps Infantry and becoming a reconnaissance officer, the Naval Academy was his target. But there was one nagging problem.

Dan Cnossen wasn’t a good swimmer.

Prior to freshman year at the Naval Academy, future midshipmen are put through the academy’s version of basic training. Dan remembers this well, thanks to the knots in his stomach and general anxiety about anything swimming.

“For six weeks or so, you're in this kind of boot camp-like environment —indoctrination — into the military and discipline and values and all this kind of stuff. Learning your classmates and belief in your company.

“But it's also upperclassmen yelling at you. It was stressful on days that we would go to the pool, which was maybe two days a week. I remember marching to the swimming pool having knots in my stomach because I was very uncomfortable with the water and I didn't know what they were going to have us do in the water,” he says.

As a kid, his basic swimming skills allowed him to control the environment he put himself in at the pool. If he wasn’t comfortable, he could swim near the sides or splash around in the shallow end. He was in control. At the Naval Academy, he lost that advantage. He was at the mercy of the training.

“I was uncomfortable with it. And so that was the beginning of my time at the Naval Academy. Not a good position to be in if you want to be considered for SEAL training.”

By design, the military wants to test you. The academies exist to train the next generation of leaders. Before he even sat in a classroom, Dan Cnossen was being tested. Fortunately for him, the anxiety of the unknown at the pool wasn’t his kryptonite. It was a problem he must solve. He did this by setting goals.

“It was about getting in the water. I knew I had other strengths in other areas — running, physical fitness, strength. But the water competency was something I thought I could acquire.”

In time, he was skipping lunch to swim. He was working with friends to become a better swimmer. For a kid who had never seen the ocean until he arrived at the Naval Academy, he found his way onto the academy’s triathlon team. Here, he overcame his slow swim times with exceptional cycling and running.

He was setting goals. He was solving problems. And soon, his next big test would be screaming toward him like a cruise missile.

There was a counter-authority undercurrent he gravitated toward at the academy that more readily fit the mold of future SEAL team operators. This appealed to him in a way the Marine Corps culture did not. These are things you just don’t know until you’re immersed in the everyday.

In his graduating class of just over 900, only 16 would be selected for Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training. And of those 16, there was no guarantee any would survive the most brutal training the military offers. This challenge appealed to him.

Later, during his senior year, Dan and most of his friends learned they had made the cut. They would have a chance to test their mettle. He was relieved and excited. But he also knew this:

“I needed to address my huge weakness of water. Then I also remember, like the very next day, thinking, ‘My goodness, I have to go to SEAL training, I have to get through this.’”

Hell Week is a fabled chapter in BUD/S lore. The grueling, punishing physical and emotional toll attempts to separate those who can succeed as SEAL Team Special Warfare Operators and those who cannot. It’s part of a 24-week curriculum that includes not just physical testing but builds the skill set required to get “pinned.” Upon successful graduation, new operators receive a Trident, which is pinned to the uniform.

As Dan looks back on his training, one specific instance serves as a reminder of what he had to overcome. Naturally, it involves water. And it would prove to be the defining moment of his training. It would require him to drill down into places he hadn’t gone, summoning the strength and courage to move forward, rather than ring the bell and move on.

“Life-saving was actually the thing that really pushed me in the water. You go one at a time with an instructor, and my instructor had played college football. And he wasn’t like a wide receiver. He was a lineman, just a massive guy. And he’s wearing a weight belt and trying to simulate drowning and taking me down with him.

“And I’m supposed to do the proper technique to keep him above the surface of the water. I failed once. I failed twice. This is not a good place to be because the next time I have to succeed. It’s three strikes, you’re out.

“I was incredibly nervous. I had been practicing over the weekend and I told myself, ‘No matter what it takes, keep his head above the water.’

“And I got through it and I didn't really know when we got to the wall how it had gone.”

Throughout our two-hour-long video conversation, I made notes — pages of them — of instances where Dan’s life intersected with specific skills he was learning at the academy or with the SEAL Teams. The things they are learning all point to a successful outcome in the most harrowing aspects of the job: combat. So I wondered: While you’re in it, are you connecting the dots?

“You're thinking about surviving,” he tells me. “If I'm going to be a good officer and a good leader, I should be thinking about the welfare of the team. If someone's been silent for a long time, checking in with them. ‘Hey, are you okay?’ This kind of thing is really just the secret ingredient of leadership.

“And if you do that — put the team first — whether you're the designated leader or an informal leader, you actually take your focus away from your own misery and pain and hardship.”

So, that would be a hard no.

The life-saving pass/fail. The Hell Week pole carry. The underwater scuba tank problem-solving. Fighting through double pneumonia. Dan was pushed to his limits. All these tests of will, of strength, of personal resolve. All the demands to lead, to perform, to serve with honor. They all get answered down range, on the field of battle.

And years later, in 2009, Dan Cnossen would need every one of those lessons to avoid becoming another statistic in America’s war on terror.

After successfully completing BUD/S, Dan was assigned to Coronado and Seal Team One. As an Ensign and a graduate of the Naval Academy, he was an officer. But guess what? SEAL Teams is the ultimate equalizer. They don’t give a shit about your rank.

“Nobody cares. Nobody cares what you’ve been through. Everyone’s done it. They don’t care if you’re an officer. If anything, it’s probably a strike against you.

“And so you're you're basically a new guy. And it can be a difficult position to be in. You want to be a sponge. You realize nobody respects you because you're an officer. Even if you may outrank the master chief of the team.

“So I think the proper approach is to be humble, ask questions and be a sponge. And that's probably good advice for anybody going into a new position. Anyway, I did a preliminary first deployment, and it wasn’t a combat mission.”

Neither was his second deployment.

Nor this third.

By the time Dan had reached his fourth deployment, he was a platoon commander, inheriting operators that had stared down the barrel of war. He was concerned about his lack of combat experience. Sponging information only went so far. He wanted his men to know he had the tools to lead them in the worst of times.

“Many of the people I'd gone to training with had gone to Iraq, were in Afghanistan. At the time, Iraq was kind of a hotter combat zone. And they were getting these kinds of missions where you're potentially in firefights.

“Being in a firefight isn't the end all, be all. And often, if a mission goes well, you're not in a firefight. But sometimes that is the ultimate end of your training — making decisions in a firefight. And I didn't have any of that experience. So I was feeling a little bit insecure, to be honest.”

Over Labor Day in 2009, Dan’s platoon was set to replace another unit. When this happens, leadership goes in first to facilitate the transition. He wasn’t on the ground more than 36 hours at Kandahar Air Base in Afghanistan when the team his platoon was replacing asked if he wanted to join a mission that night.

Dan didn’t hesitate. He geared up and boarded a helicopter heading for southern Afghanistan. The high-value target (HVT) was clustered in a remote mountain valley.

The distance to target was substantial — more than an hour. Dan remembers everyone riding in silence. It was dark, and the inside of the helicopter was blacked out for security. The air thick with intensity; the geography below lit by the grainy green and black of night vision goggles.

Smoothly, swiftly, the chopper sliced through the Afghan night before arriving at the insertion point. The team got out, set up and started patrolling. They were in Helmand Province, a rural area heavily controlled by the Taliban. Dan wasn’t on the assault team. He was assigned overwatch, which meant they had to take and secure a structure at the top of the hill that overlooked the target compound.

“We're walking in the middle of the night with night vision goggles, climbing the hill. It took a decent amount of time to get to the top. It wasn't a mountain by any means, but it was a large hill.

“And when we got to the top, it was more of a plateau. We had kind of spread out and I’m looking through the night vision goggles, and at some point it was a flash of light and I was on the ground.”

Dan’s memories of the ensuing events are like a film strip missing key frames. He remembers lying in the dirt. I must have stepped on an IED pressure plate. He remembers it being dark. I can’t see. He thought maybe he couldn’t see because his helmet and night vision goggles had been blown off his head. I don’t remember being launched. Later, teammates would tell Dan the explosion sent him airborne.

His friend in the unit told Dan this: He heard a massive blast, looked with night vision at the top of the hill and saw a column of mushrooming dirt and debris. Everyone must be dead, he thought. Radios crackled with pleas for a response. It seemed like minutes. Nobody responded. Are they alive? Did anyone survive?

Dan was still in the dirt, disoriented and severely injured by a 105mm artillery shell that shredded his lower body. He would later learn there were two, and one didn’t detonate. If it had, he likely would have been killed instantly.

Next, as consciousness begins to fade, he reaches for his radio. I need to say man down. Where is it? He reaches around in the dark. Hands and fingers combing the ground, coming up with nothing but dirt, rocks, debris. He couldn’t find it.

He feels panicky. Faint.

Worry enveloped him.

Within moments, the team he had just joined for this excursion — the one his team was replacing — was on him like one of their own. Man down! Everyone did their thing. Thankfully, no one else was seriously injured. Dan’s injuries were enough to handle. Anything more could have divided resources with a catastrophic outcome.

“I remember the tourniquets being applied to my lower limbs and I couldn't see anything. Maybe that was good. I couldn't see what was going on, the damage. But the tourniquets, I think there were six, three on each leg. That's really, really a tough thing to go through. It is painful. Most certainly, I was in shock, but I wasn't feeling pain prior to that.”

Dan suffered a double femoral artery rupture. One leg was gone. The other was dangling by threads. He would bleed out in 90 seconds without the decisive action from his band of brothers. While he’s being tended to, there’s another dramatic scene unfolding.

The helicopters were returning to Kandahar. They were scheduled to churn back to this mission later. The SEALs managing this chaos got a chopper to turn around for Dan immediately. This was dicey. With such a great distance between the insertion point and the airfield, fuel was a key factor.

The pilots refused to land at the top of the hill — closer to Dan — because it would make the silhouette of the chopper a giant target for Taliban rocket-propelled grenades. The team would have to drag him down the hill to the landing zone. Fuel was tight. Dan was critical. Time was no one’s friend. Everyone’s life was potentially hanging in the balance.

The men caring for Dan knew his survival depended on getting on that chopper. They had to drag him down the hill. Quickly.

It was gnarly.

Six tourniquets.

His body sliding over the craggy mountainside.

One leg dangling.

The pain was more than anything he had experienced.

A violent explosion that sent him vertical.

The jagged edges of rocks and the razor-sharp terrain tearing through his already mangled and shredded gear, scraping his skin raw.

Stay awake.

Finally, they reached the chopper. They had one minute before the “bingo fuel point.”

“All of that stuff had to really line up for me to even get onto the helicopter. And then that's when I let myself go.”

Darkness.

Eleven days later, Dan Cnossen woke up in a hospital in the United States.

Dan’s mom was the first person he saw when his eyes opened from a medically induced coma. He was at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland. Soon, he would be told what he feared most: his legs were gone.

Pieces of what happened that night in Afghanistan — and the ensuing days after — began to trickle in. The unit he joined that night stayed in the fight and remained on the ground through another cycle of darkness.

When they returned to Kandahar Air Base, they visited the ICU to check on Dan.

“The doctors at the time were saying it’s not looking good,” Dan was later told. “So it was more of them kind of saying goodbye. I was told the senior ranking SEAL at the time was in Afghanistan, and he was going to try to get a Purple Heart on me.”

But Dan didn’t quit on himself. He believes an “existential survival mechanism” kicked in, aided by expert care. He bounced around two bases overseas before finding himself on a hospital plane to the United States.

Months of rehab stared from the depths. His sister, who at the time was just starting her nursing career in New York City, came down to Maryland and lived with him, helping with daily care.

Calendar pages whipped past. Months of getting better were marked by various stages of prosthetic advancements. He wondered about his future. Stories he’d heard of amputees returning operational weren’t entirely accurate. But he could still serve in some capacity.

And then he had a plan: I’m going to run.

He was walking without a cane and no longer used a wheelchair. Then, on Sept. 8, 2010 — one year to the day — he went to the track with a friend.

“I ran four laps around the track, continuous,” Dan says. “I did one lap. I felt good. I did the second one. I felt good and at that point I'm going to do the mile, and then I felt like I could start training.”

Around this time, he learned of opportunities in the Paralympics. A sports camp he attended in San Diego delivered fate to his doorstep: Two Nordic coaches from the Paralympic team. They extended an invitation to a camp held months later in West Yellowstone, Montana.

Although he didn’t even know how to keep his stumps warm, potential was spotted. “I never set out to be a Paralympic athlete, but this fell into my lap and I liked it.”

Cross-country and biathlon allowed Dan to experience the thrill of being in the woods again, just like this youth on the family farm in Kansas. The thrill of propelling himself across the snow, using his rifle skills to take down targets — it all felt good and familiar.

Before long, he’s in Colorado, training at the National Sports Center for the Disabled in Winter Park. He has a coach. “My first coach was really, really instrumental in teaching the ways of the athlete. It was a whole new way to live.”

In the Teams, there was a lot of sit-around-and-wait. You train, you pound some beers later that night. Train some more. Always being ready to spin up and head down range.

As an athlete, that routine doesn’t work. Sleep. Hydration. Rest. Meals to fuel your workouts. Being an athlete was all about high-performance training around the clock. Dan poured himself into this new lifestyle vessel. “I was training my butt off. I had my plan. I'm thinking I’m going to add an extra workout every day. Just doing the whole Maverick thing. I was putting pressure on myself and the pressure manifested in overtraining.”

Dan earned a spot at the 2014 Sochi Paralympics but never felt podium-worthy. The overtraining hurt more than it helped, and mentally he wasn’t in a place that felt comfortable. But the experience mattered and filled his tank with knowledge on what could go wrong — and how to amend his future plans. He left Sochi wiser.

The path to the 2018 Pyongyang Paralympics was quite different. Dan was in two graduate school programs: The Harvard Kennedy School of Government and a divinity program where he studied Buddhism and the Eastern mindset.

“I didn't have time to overtrain. I had this whole other focus. I was meeting new people, learning new things, taking cool trips. It just took my mind away from training, competing and results.

“I had been focused way too much on results. And then just having this kind of new approach to what it means to operate in the moment. That served me well going into 2018.”

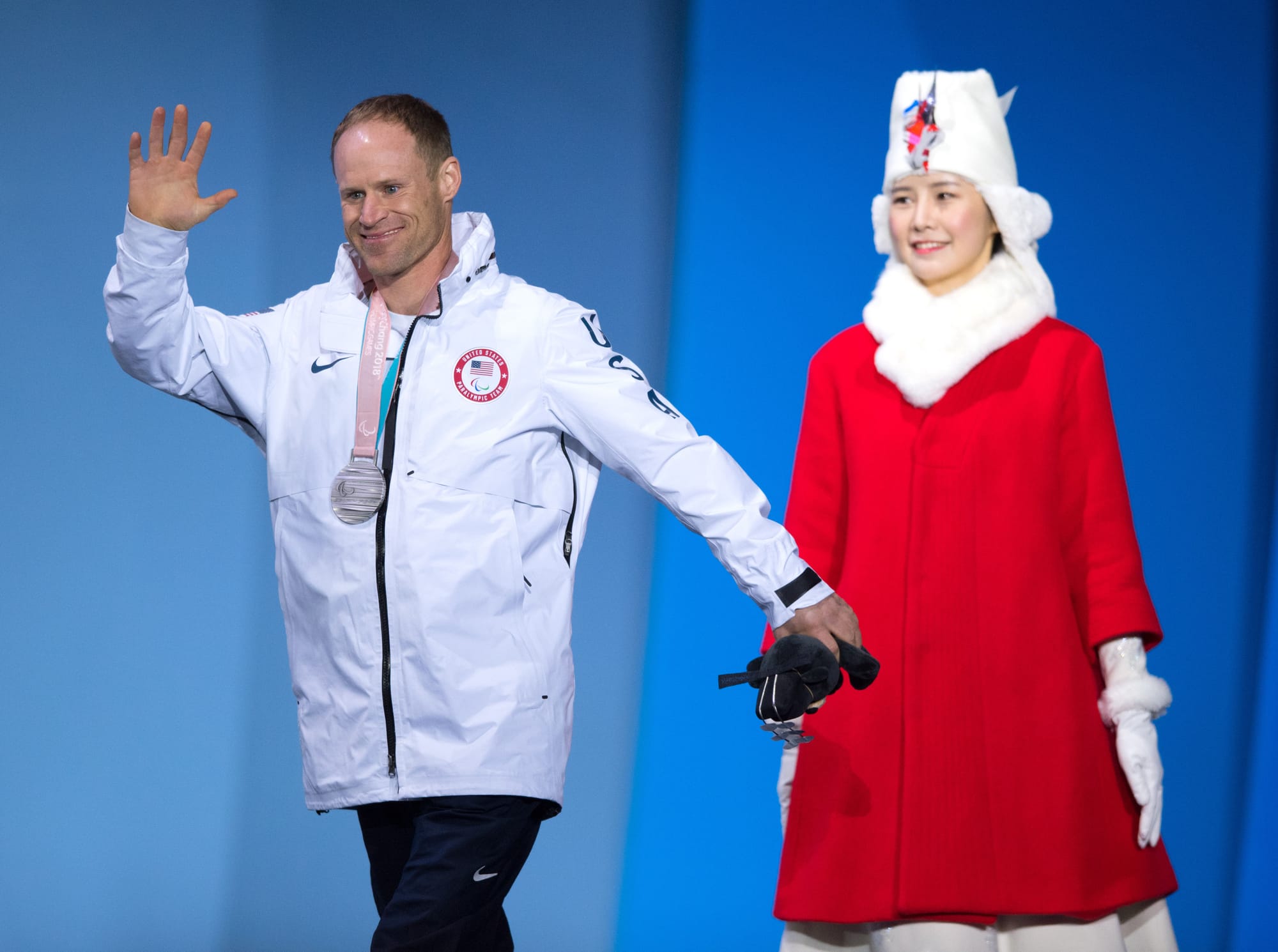

Whether he was better prepared, more relaxed, less distracted — pick your solution — Dan became the star of the 2018 Paralympics. He won one gold, four silver and one bronze in a span of eight days. He was named Best Male Athlete of the Games.

“I think instead of focusing on the end result, you're focusing on really the way that you're going to get your best result. And it's a subtle thing that's kind of where I put my effort. And yet society kind of judges that based on the medals and this kind of thing. So I had gone to Sochi, same person, really the same story, and didn't walk away with a medal.

“But when I came out of Pyongyang as a medalist, there were opportunities.”

These include the public speaking circuit, possible endorsements, appearances, and much more. But he had caught Paralympic fever and found himself training for Beijing in 2022. There, he grabbed another gold medal for his collection.

Now in his early 40s, Dan is still seeking fulfillment. Spiritually, emotionally, physically. He’s not ruling out 2026 in Milano-Cortina. In some ways, he’s willing to let this vessel of experiences steer itself.

When he talks about his Paralympic achievements, he’s quite understated. Even subdued. Almost as if he hasn’t impressed himself. Let others be in awe. I’m not interested.

He has dropped biathlon as a discipline to focus more on cross-country skiing. He feels most at home here, pushing his limits in nature. I pointed out to him that we started our conversation nearly two hours ago, talking about running around the woods on his family farm. And now he’s talking about the rush he gets from essentially the same thing — except he’s on a sit-ski.

“I think you can come away from an injury like this a stronger and better person, but you still have the core of who you are. I don’t think I was radically transformed by this. I’m the same person.”

Perhaps. But the boy who loved adventures on the farm left home for the Naval Academy without confidence in his skills as a swimmer. He then captained the triathlon team to a national championship. The man who became a SEAL and platoon commander without combat experience left the battlefield fully engaged in the most important fight of life. And the person who came out of the darkness of a coma bottled his experiences and brewed a recipe that netted seven Paralympic medals and counting.

“In some ways I’ve been falling back on who I was,” he admits. “But then also doing it in new ways. It ended up being the only direction I could go.”

Advertising and sponsorship opportunities are available. Contact Jim Hoos at jhoos@r1s1sports.com or 602-525-1363.