Hannah Kearney was studying for a sophomore midterm at the kitchen table of the Norwich, Vermont home that her dad built when she got the call that would set her life’s trajectory.

You’ve been identified with potential for a future in moguls, said Dee Williams, the development coach from the U.S. Ski Team. Would you be interested in being a forerunner for the women’s moguls event at the 2002 Salt Lake City Games?

“I blacked out,” Hannah recalls. “I was supposed to be studying for an algebra exam. I remember that because I didn’t do well on it the next day.”

That call may have cost her a 4.0 grade point average (she finished high school with a 3.97), but the tradeoff? Not so bad.

A few weeks later, 15-year-old Hannah glided off a Deer Valley chairlift and glanced down at the grandstands built for 15,000. They were empty and quiet in the bluebird stillness of that moment, but she imagined the dancing, cow-belling and multi-lingual screaming to come.

Whether you ski or not, you know moguls ain’t easy. Which part of the bump do you ski? When do you transition? How can you possibly make decisions fast enough to stay upright and in line? And yet “moguls” severely understates the actual difficulty of the competition.

Not only do athletes ski a timed run down a mogul field, but they also launch into tricks off of two jumps along the way. On the bumps, knees and skis are glued together, torso upright, and off the jumps, you want air and grace. Judges score each run based on the skier’s turns, jumps and speed.

As a forerunner, it was Hannah’s job to ski the Olympic course ahead of the competitors to test timing, safety and conditions. She remembers being so much slower and weaker than the field, but everyone was nice to her, and she got to wear a bib with those five hallowed rings. And for the first time, she was able to watch the best skiers in the world compete in person rather than on TV.

“Shannon Bahrke skied an electric run to win silver, and all of a sudden, it was very attainable. It made me realize what it would take to get there. I knew I was inferior, that I needed to learn some new jumps, but I thought, ‘I can do this.’”

As soon as she got home, she resolved to learn a new trick: a 360. It took a week of “a lot of crashing,” but she got it and incorporated it into her next two competitions, including the Junior World Championships two weeks after turning 16. She won those championships and with them an automatic spot on the U.S. Ski Team — just weeks after forerunning the Winter Games.

That was just the start. She went on to tear it up throughout high school, competing in World Cup events she could drive to, while also playing soccer and running track. In the fall semester of her senior year, she loaded up on courses so she could graduate in January and travel the full World Cup circuit. That season, she earned her first podium in Finland and her first gold in Japan.

The following season, while her friends went off to college, she won her first World Championships — the best of the best.

That kind of success was perhaps the natural progression for a kid who learned to ski while strapped into the family draft horse’s halter as a toddler, gravitated early to trees and bumps, and started competing in sanctioned events at age 8.

So with the 2006 Torino Games just ahead, Olympic gold seemed plausible, maybe even a gimme.

Except it wasn’t.

Without high school soccer and track, Hannah’s conditioning and focus suffered. She’d always thrived in an environment where she had to manage academics, high school sports and skiing. Leading up to Torino, skiing was … it. Even your favorite yin in the world can become an unwieldy weight when there’s no yang.

She wasn’t training the right way and went into the Olympics trying to treat it as not the Olympics.

“If I focused on the same judges, the course, the skill set, and ski the same run I won the World Championships with, I should have a gold medal. What that doesn’t acknowledge is the extra pressure.”

At 19, she was “kinda snarky and an immature bundle of nerves” who felt intense pressure to perform for her family and the well-meaning Norwich supporters who’d organized a send-off parade for her.

Never a stranger to the podium, Kearney once won 16 consecutive races. [AP photos]

But in her first run, she bobbled at the top and again after the first jump. Disastrous. She placed third-to-last — not enough to advance to the finals, let alone medal.

That was a tough pill, the kind that can make you wallow.

“I’m not that good at just being like, ‘change your attitude.’ My mom gave me a book called Happiness Is a Choice, and I wanted to throw it out the window. I had to experience the sport being taken away from me, having a sport that I literally didn’t remember living without.”

That moment came in France the following year during a training run before a World Cup final. She didn’t fall but jammed her knee, felt a nauseating cramp and slid down the rest of the course. ACL reconstruction awaited.

Instead of celebrating her 21st birthday living out of a suitcase and traveling from event to event, she was home on crutches, alone with her thoughts.

“You think, should I have gone to college? My friends are having the time of their lives, and now here I am, injured, sad, by myself. But then eventually, it also made me really grateful. Rehab forced me to learn about my body and how to train for mogul skiing.”

And that’s when she came to appreciate the power of experts and metrics. Physical therapists and strength and conditioning coaches helped her rebuild her power and mobility. Later, jump-specific coaches helped her get back into competition mode.

Through all that work, she learned the value of having a team around her — people who believed in her and had expertise in areas that she didn’t.

That expertise complemented her goal-oriented nature, giving her productive, concrete benchmarks to conquer. Had she increased the range of motion in her knee? Could she squat heavier weight this time? Had she added any girth to her quad since last week?

“I liked to pretend that I was a machine, and I put the inputs in to make the machine better.”

A stronger physical machine led directly to a stronger mental one, too, and that combination led to breathtaking consistency for the rest of her career. When she was cleared to compete, she began earning World Cup podiums again and in 2009 earned her first Crystal Globe, the trophy awarded each year to the World Cup overall moguls champion.

Once again, results and momentum seemed to be lining up just right for the Olympics. Could she deliver in the 2010 Vancouver Games?

“I felt like I was working harder than anyone else, and that gave me a confidence in the start gate that I couldn’t fake. I had to know I could squat more than anyone else and that I’d done everything to address my weaknesses and prepare for the moment.”

She was the last skier to go in the finals on a damp, drizzly evening at Cypress Mountain in West Vancouver. Teammate Shannon Bahrke was in second place and Canadian Jenn Heil in first. In the starting gate, Hannah took a deep breath, adjusted her collar and then flew down the course and into a clean back flip, a flawless middle section, and “the heli she needed,” as announcer Jonny Moseley called it.

Scoring almost a full point ahead of Heil, she’d done it. Gold. Redemption. It was a result only sweetened by the disappointment of Torino and long slog of rehab.

Sweet, but not perfect. Soon after, she saw the footage of her run from the judges’ view, a straight-on look from the bottom of the hill that revealed a flaw not visible from the TV camera angle.

“My back flip was really crooked. And I thought, oh my god, I could make this so much better. In mogul skiing, speed is objective and everything else is subjective, so you’re trying to make the most beautiful package. That flip was an ugly blemish on what was otherwise a gold medal run.”

And so began a new set of benchmarks.

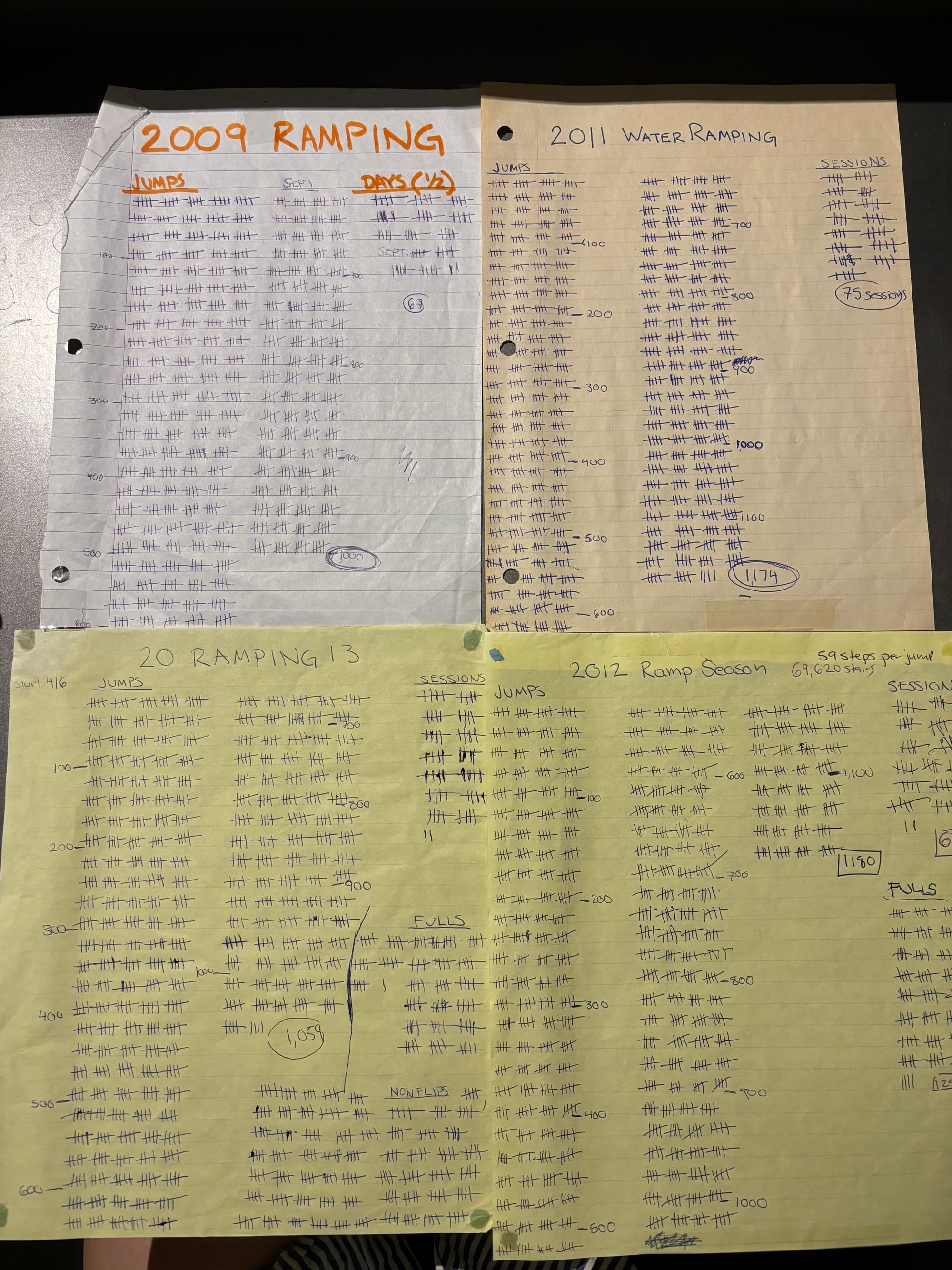

By really crooked, she means five degrees off-center. She spent the next four summers doing 1,000 jumps into a pool to straighten out that backflip and otherwise perfect her jumps. One thousand literal jumps, or figurative? Literal. She knows because each day, she tracked every jump using a carabiner attached to a chain link fence at the Lake Placid pool, and then she’d head back to her dorm to log the day’s tally.

It was one more metric she could track and use to feed the machine. And as you might expect, it polished and brought consistency to her craft. She won 16 straight competitions between January 2011 and February 2012, beating Swedish slalom great Ingemar Stenmark’s record for the longest International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS) World Cup winning streak across all disciplines.

In all, she’s won Vancouver gold and Socchi bronze, 40 World Cup moguls medals, six moguls titles, four overall moguls titles and two overall freestyle titles.

After a painful season that required getting her “meniscus cleaned out,” she retired in 2015 with her final Crystal Globe, earned her marketing degree and personal trainer certification, and settled in to Park City, Utah, where she lives with her husband and 14-month-old daughter.

She works with U.S. Ski & Snowboard Foundation, the national team’s fundraising arm, to support training and development for today’s athletes.

Training will always be part of her life, both for herself and others. She still goes to the gym every day and also builds programming for elite athletes to help them peak at the right time.

And she’s continued the passion project that started during COVID-19: online workouts for people who want a program themselves. She calls it Fitness From Afar, and her annual ski-prep challenge begins October 28.

It includes live Zoom workouts, a Facebook community, and true to form, a point system for tracking strength and conditioning progress and staying accountable. The whole point is to get in ski shape, help prevent injuries, and maybe even get better on the slopes. Because you can always get better, Hannah says.

“To this day, I’ve never skied a perfect mogul run.”