There’s a note on Kamali Thompson’s computer called “badass accomplishments.” It’s a detailed list of all the things she’s most proud of in her 31 years. It goes in order:

1. 2011 Student-Athlete of the Year

2. 2012 NCAA All-American

3. 2012 Student-Athlete of the Year

4. 2012 NCAA Woman of the Year candidate

5. 2016 MBA

6. 2016 Olympic alternate

7. 2020 Olympic alternate

The note continues: articles in USA Today, the Washington Post, Teen Vogue, Sports Illustrated. She’s had her picture on a billboard. She was named to Temple University’s 30 Under 30, which spotlights trailblazing alumni. She was recently inducted into the university’s athletic hall of fame.

“I can’t believe it honestly,” she says scrolling through her note. “When I was in the thick of everything, none of this stuff was on my list of things to accomplish — other than be an All-American and an Olympian. It’s almost a dream, like ‘I really did all that?’”

She did. All of that. And so much more. Not bad for someone who never wanted to play a sport that has helped her ascend to such great heights.

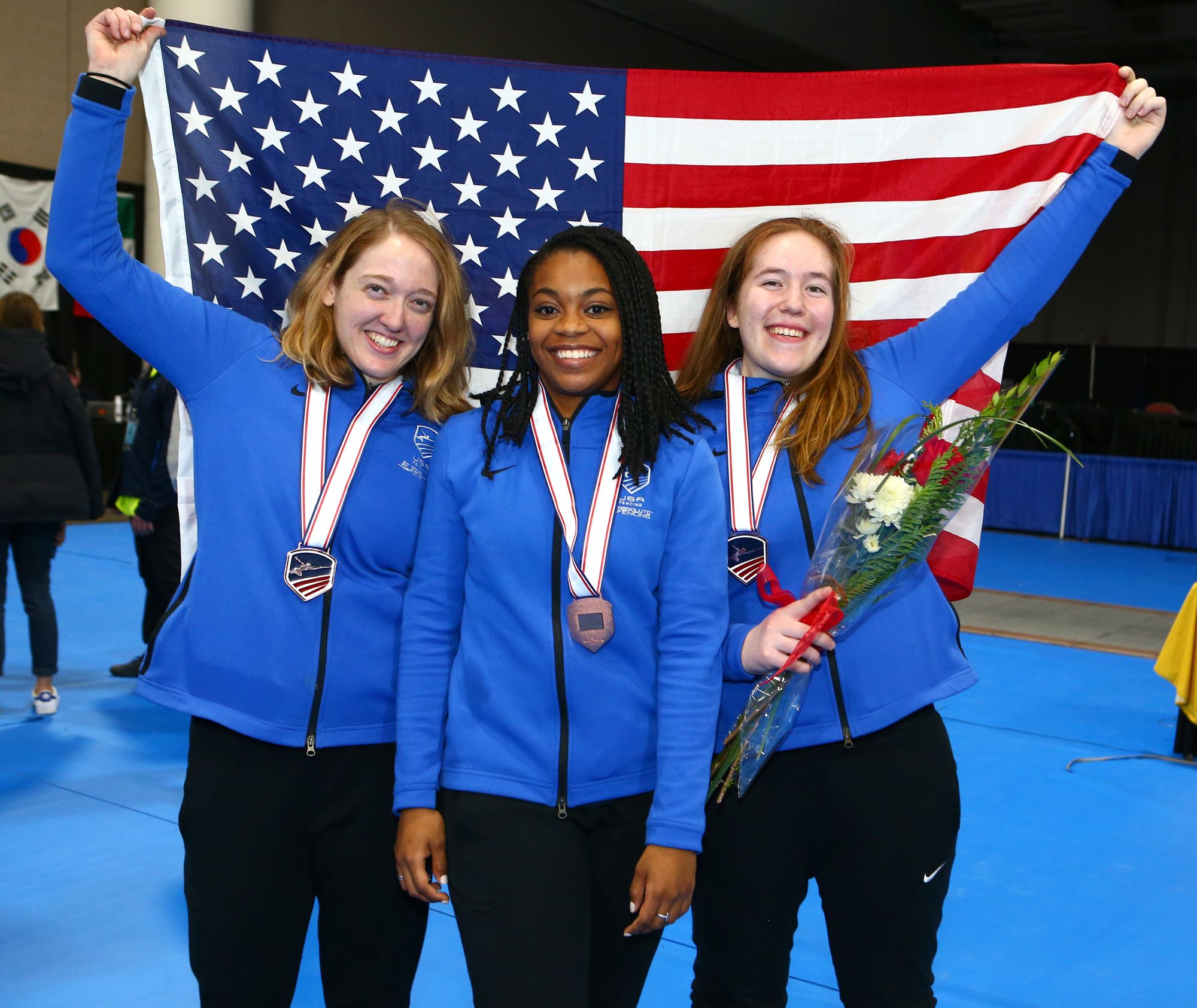

While she preferred to be a dancer, Kamali finally found herself with fencing. [Getty Images left/right; courtesy image center]

No, back entering her freshman year of high school in Teaneck, New Jersey, which borders New York, Thompson only wanted to dance. She was 12 years old, incredibly young for a freshman after having skipped pre-kindergarten and kindergarten and flying straight into first grade. “It was really difficult socially for a while,” she admits.

Thompson had no interest in fencing, this obscure sport with weird uniforms, goofy-looking helmets, and swords that aren’t quite swords. She wouldn’t earn any cool points doing that! No, all the cred went to the cool kids who were dancing and flag twirling. She was going to do that! But as she stared inside the high school gym, she watched her mom talk to the fencing coach with increasing enthusiasm.

Listen, I think fencing is going to put you on a trajectory that is going to take you much further than dance or flag twirling, her mom would later tell her.

“All I could think was ‘This is terrible,’” Thompson recalls today. “‘I don’t want to do this. You’re taking all my social credit.’”

Fencing, her mom reasoned, would offer many more opportunities for college. Plus, Thompson’s dance school had recently closed and there wasn’t enough time in the day to drive 30 minutes to a new school after work.

Okayyyyy fiiiiiiiiineeeee, Mooooooooommm.

Thompson struggled her first two years as she learned the sport. It’s one that requires technique and smarts as you’re trying to use all your strengths to expose your opponent’s weaknesses. As Thompson says, “To put them in a trap so that they can play into your strength.”

Her strengths are making people miss and counterattacking. Defense has always come naturally to her, a trait she quickly learned in high school. What she lacked in technique she carried in instinct. So when her opponent tries to hit her, she says, “I was trying to get out of the way, and I would hit them.”

Thompson joined the Peter Westbrook Foundation her junior year, one of the most successful and influential fencing organizations in the U.S. It was founded by Peter Westbrook, a six-time Olympian fencer and the first Black man to ever win an Olympic medal in fencing. Being immersed within a diverse group of fencers was eye-opening to the young Thompson. There were Black athletes who were not only Olympians, but who had graduated from prestigious universities and held high-profile jobs. In her mind, the possibilities of what she could accomplish swung open, and Thompson was ready to rush through.

Soon, Thompson began picking up the finer details of the sports, which led to winning matches. She traveled to bouts throughout the U.S. and got recruited by colleges. She always pictured herself going to an Ivy League school, but settled on Temple University in nearby Philadelphia. It wasn’t her first choice. She wasn’t enthused about going to a college that so many from her high school attended, but it had a strong fencing program with a coach, Dr. Nikki Franke, who was a two-time Olympian.

There she blossomed in her sport, earning four consecutive berths to the NCAA Championships while being named an All-American. But she always had bigger ambitions. Yes, she wanted to be one of the best fencers in her sport, but she had dreams of becoming a doctor from way back to when she was a little girl. She received a doctor's set one Christmas filled with a toy stethoscope, syringe, and scrubs. She loved visiting her pediatrician, an older Black woman whose office was filled with colorful pictures and paintings that emitted a peaceful vibe.

“I loved how I felt when I went to her office,” she says. “And I want to make other people feel that way, too.”

And she loved getting shots and the lollipops afterward.

“After 12 when you stopped getting vaccinated, I was so upset,” she admits with a hearty laugh. “I’m not normal, I know.”

So, it’s no surprise she chose medical school after college graduation. Perhaps what is a surprise is that she continued fencing. She, of course, excelled: a silver medal at the 2015 Division I Women’s Sabre National Championship followed by a gold medal the following year. She worked her way up to sixth in the Team USA rankings and had a chance at one of four spots to the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

Through all this, she took a year off medical school to get her Master of Business Administration. If she was going to be a pediatrician with her own practice, she reasoned, she would need to have a firm understanding of running a business. She graduated with her degree at the same time she was attempting to qualify for the Olympics.

She was finally feeling comfortable in her lane, understanding the principles and techniques that would carry her to one of those four coveted spots. She spoke with friends and family about her Olympic goals, she held fundraisers to pay for her training and travel, news articles ran about this Olympian hopeful who doubled as a future doctor. And therein rose a problem: All this attention and pressure paralyzed her as she competed — her fear of failing so strong that she never gave herself a chance to succeed.

“I was so angry because I knew I could do better,” Thompson says. “But I was literally standing on the strip and I didn’t know what to do.”

If she was ever going to qualify for the Olympics, Thompson knew she had to change her mental approach. Rather than focusing on failure, she began a visualization routine where she saw herself achieving difficult moves and winning tournaments. She leaned on a sports psychologist who also helped shift her mindset. She instilled a mantra she repeats to herself regularly: “You are smart. You are amazing. You deserve to be here.” It’s one that not only helped in fencing but one she uses to this day during her residency as an orthopedic surgeon. Letting go of her fear allowed her to blossom.

“With all of it, it’s crazy how quickly my brain started to believe what I was trying to do,” she says.

She won back-to-back silver medals at the Division 1 Women’s Sabre National Championships in 2018 and 2019, and later won a Pan-American team championship in 2019. Her sights were set on the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, a time when she was fencing the best of her career. Thompson held one of the four sports to qualify for Team USA and compete in the Olympics. All was playing out to her plan: qualify and compete in the Olympics and return to finish her fourth year of medical school.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic that delayed the games for a year. Suddenly, she found herself splitting time between medical school and a particularly grueling year as she prepared for residency and training for the Olympics — all of which she purposely tried to avoid.

During a World Cup event, Thompson had a good showing, but so did a teammate, who managed to jump her in points and slide into Team USA’s fourth Olympic spot. Thompson wasn’t too concerned because there was one World Cup event scheduled before the Olympics and an opportunity to regain the final spot.

But COVID reared its ugly head again, leading organizers to cancel the event and leaving Thompson the odd fencer for Team USA. Years of hard work and planning and training and delaying medical school were all for … nothing. She was named an alternate, and in the event any of Team USA’s qualifiers caught COVID or couldn’t compete, she would fill in.

“That was tragic,” she says. “Because of this pandemic, that opportunity was taken away from me.”

She also watched as her brother qualified for Team USA men’s fencing team, which left her torn emotionally. On the one hand, she wanted to cheer her brother on; on the other, she was sickened she wouldn’t compete.

After the Olympics, Thompson retired from fencing after 18 years to focus on her career as a doctor. She completed medical school and is now in her third year of residency. She’s no longer planning to open her own pediatric practice. During her third year of medical school, she fell in love with orthopedic surgery and the idea of helping athletes return to their best selves.

She’s finding there are a lot of similarities between fencing and surgery. For one, you have to be hyperfocused both in your lane and in the operating room. You have to build a solid plan of attack and study your opponent. You must plan for when things go awry and how to fix it.

“There are so many lessons I’ve learned from fencing that are going to make me a great surgeon,” she says.

Though her days are now consumed with long hours in a hospital, she admits there’s a void left by fencing. She’s now focusing on tennis, which, like fencing, she admits she’s getting started much later than most. That’s okay. That’s never deterred her before.

“The fact that if you’re starting anything late, whether it’s a sport or transitioning careers, if you really have the drive and passion and you’re able to find people who can support you and lead you in the right direction, you can do whatever you want to do,” she says.

She plans to hire a coach and spends her off time studying matches and picking up different strategies. She’s talking like she could be gearing up for another Olympic run one day.

“I can feel my competitive energy building,” she admits. “We’ll see how competitive it gets, but I’d say pretty competitive.”

So, here she is, a 31-year-old doctor using her passion for sports to treat athletes. She’s been to the Olympics. Survived medical school. Gotten her MBA. And now might one day be eyeing a side career as a tennis player. Is there anything Kamali Thompson can’t do?

“Yeah,” she says. “I’m not going to law school.”