“How about the way that Marlins game ended last night?”

Larry Bowa had just slipped into a booth at Gullifty’s, an upscale bar & grill in the tony Philadelphia suburb of Bryn Mawr and he entered talking baseball. Well, of course he did. He’ll turn 78 in December, but the game still absorbs him. He still puts on a uniform in spring training and works with the Phillies infielders. Still has a relentless curiosity about every nuance of the sport, taking it apart and putting it back together in his mind.

At this moment, the fact that Miami’s game against the Mets had been suspended in the ninth inning because of heavy rains at Citi Field had captured his attention. With the playoffs set to begin in days, there was a chance the Fish would have to fly back to New York to play just one inning. The implications were intriguing. How that might impact the pitching plans and the routines of not just the Marlins but also the Diamondbacks and Cubs, the other teams in the wild card race?

During the next hour-and-a-half, over chicken fajitas, the full range of Bowa’s restless baseball intellect was on full display. The new rules MLB had enacted. Padres closer Josh Hader’s refusal to pitch more than one inning earlier in the week. His agitation when he disagrees with another manager’s decisions or gets frustrated by poor fundamentals. How the Phillies might set up their rotation and bullpen in the Wild Card Series.

He was 20 years old when he played his first professional game for Class A Spartanburg in 1966. He went on to have a 16-year big league career then coached, managed and worked as an analyst for ESPN and the MLB Network before settling into his current role as senior adviser to the general manager in 2017.

Connie Mack was a baseball lifer. He has a statue outside Citizens Bank Park that attests to his 50 years as manager of the Philadelphia Athletics and 71 years in the game overall. Don Zimmer. He had a 66-year career – with the Rays his uniform number increased each season to correspond with his longevity – and proudly bragged that every dollar he’d ever earned came from baseball.

Tommy Lasorda. Jack McKeon. Paul Richards. Johnny Pesky. Wayne Terwilliger. There are others, but it’s a pretty exclusive club.

Bowa checks all the boxes. What makes him unique, though, is how thoroughly unlikely his journey has been.

Has anybody else spent nearly 60 years in baseball after being cut from his high school team three times?

Have any achieved that sort of longevity after going undrafted?

And have any been welcomed back by an organization, in this case, the Phillies, after previously being shown the door three times? And twice figuratively torching both the Ben Franklin and Walt Whitman bridges on his way to the exit?

Surely not.

“I played with a chip on my shoulder,” Bowa said.

Late in his spectacular career, Tom Brady was asked if he could name the six quarterbacks who were drafted ahead of him in the 2000 NFL draft. He rattled off the names. Chad Pennington. Giovanni Carmazzi. Chris Redman. Tee Martin. Marc Bulger. Spergon Wynn. All off the board before Brady went to the Patriots in the sixth round with the 199th overall pick.

Nobody-believed-in-me-but-I-showed-them is the oldest, most tried-and-true motivational technique in the world. Bowa took it up a notch. He honed the slights until they were razor sharp. Nurtured the grudges until that chip on his shoulder was the size of Rhode Island.

It wasn’t just that he didn’t make the high school team. “(The coach) said I was too small. He didn’t say I wasn’t good enough. He said I was too small,” Bowa said, still nettled after all these years.

And it wasn’t just that after 63 rounds and 833 names were called in June 1966 that not a single team had seen fit to draft him. “Then you sign a contract and they tell you when you sign it that you’re going to be an organization guy,” he said, the wound still raw. “And if you only get to Double-A maybe we’ll keep you in the organization as a coach or manager.”

Five All-Star Games. Two Gold Gloves to go along with 2,191 career hits. Only get to Double-A? Shove it in your ear.

“And then (Associated Press sports editor) Ralph Bernstein, God love him, wrote an article saying I’d be lucky to get a hit in Williamsport. Called me a Little Leaguer.

“I kept all that stuff. I kept it and when things were going bad, I’d read it again. I kept all the things were negative. I didn’t keep the positive stuff. I wanted to have that edge the whole time.”

He still has those clippings at his home, by the way.

“When I first came up, guys would get on me. ‘What are you running so hard for on a comebacker to the pitcher?’ I was just taught to do that. I didn’t let that sway me,” Bowa recalled. “Pete Rose said when he first came up some of the veterans said, ‘You can’t run to first on a walk. You’re showing everybody up.’ He said, ‘That’s how I play.’ You’ve got to stick to what you believe in.”

Bowa is a member of the Phillies Wall of Fame and one of the most popular former players in franchise history. As a result, he’s part of a pregame ceremony at least a couple of times each season.

“When I get introduced now and I run out and Bull (Greg Luzinski) gets the ass,” he said. “He’s grabbing me, says I’m trying to show him up. I say, ‘I’m not trying to show you up. But there may be a day when I can’t run out here. So as long as I’m able to and I’m in good condition, I’m doing it. And if you don’t like it, tough shit.’”

That raging sense of competitiveness carried across the foul lines. Longtime Phillies coach John Vukovich, one of his best friends, loved telling the story about the time he took his young daughter, Tori, to play putt-putt golf during spring training. “He wouldn’t let her win,” Vuk would say with a chuckle.

That’s the short box score version of how Bowa’s inner fire was kindled, how the flames remained stoked decade after decade. The full story is more nuanced and, as is so often the case, begins with his upbringing.

Paul Bowa reached Triple-A and later managed in the Cardinals farm system. To this day, Larry is acutely aware of all the things his family, including his mother, Mary, and sister, Paula, did without so he could play baseball.

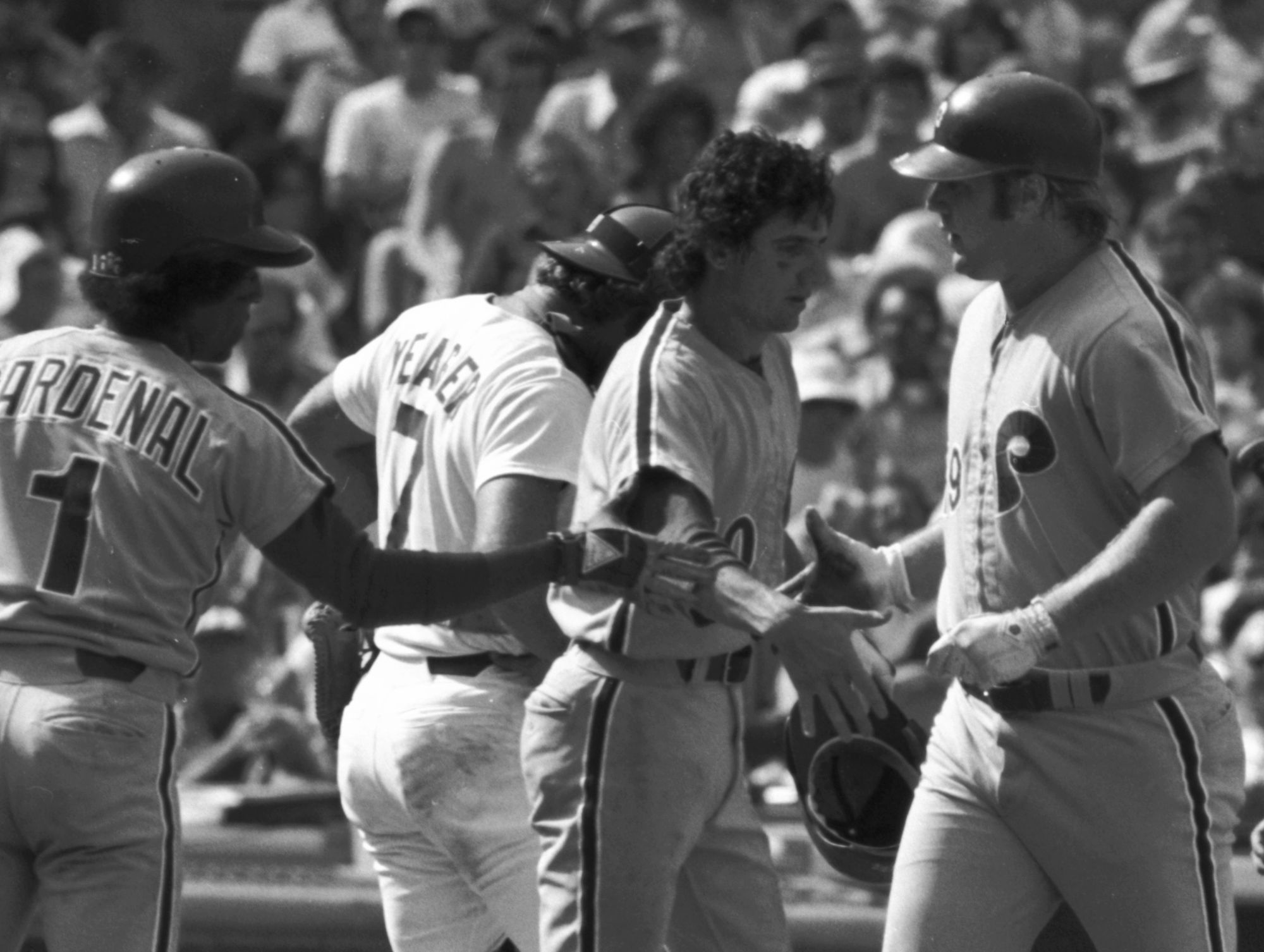

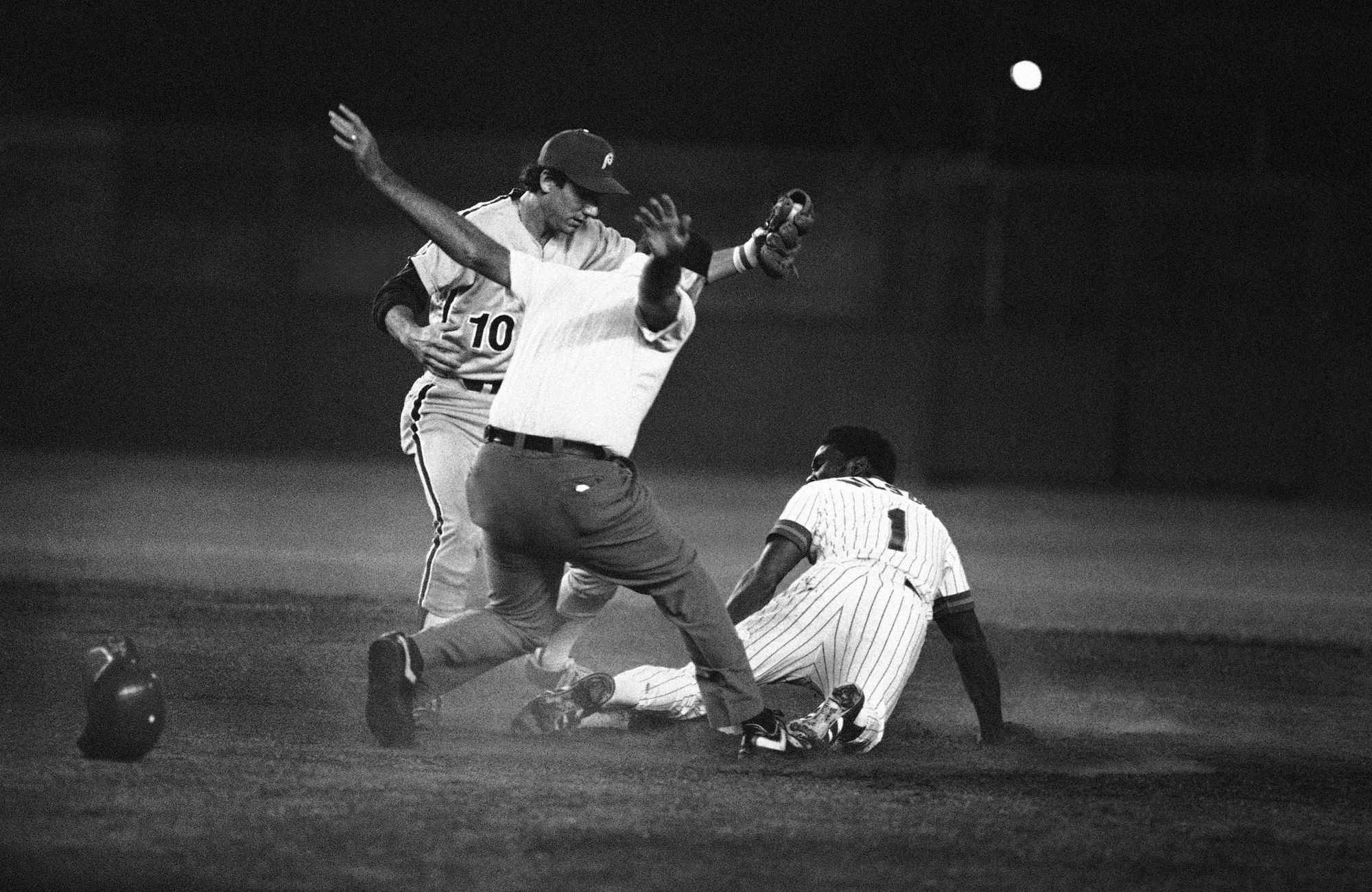

A two-time Gold Glove Award winner, Larry Bowa held the National League record for career fielding percentage by a shortstop when he retired. [AP photo]

After baseball, his father worked in a printing plant. He died of emphysema, likely caused by exposure to the ink and chemicals.

“He worked two jobs all the time. We didn’t have a lot of money but what I needed, he got me,” Bowa said. “There was always a ball in the house. And not one time did he say, ‘Hey, I want you to be a baseball player.’ But there was always a bat or a ball. I was always picking it up and throwing it. Every time we’d work out it would be my idea. He’d never come home and say, ‘You need to go do this.’ Because he wanted me, if I was going to play baseball, to love the game and not force it on me. Those are memories that last forever.

“My mom and my dad and my sister, they sacrificed a lot. I always played summer league. So instead of going on vacation, they’d say Larry’s going to play.’”

Paula, in fact, went through it twice. Nick Johnson, her son and Larry’s nephew, had a 10-year big-league career with the Yankees, Nationals, Marlins and Orioles. “To this day, my sister and I talk about that,” he noted. “All the stuff she sacrificed. Because she’s really done that her whole life. With me and with Nick.”

There were others. Phillies veterans like Cookie Rojas, Tony Taylor and Bobby Wine who took him under their wings and drilled into him the importance of playing the game the right way. Gene Mauch, who was the manager the first year he was invited to big league camp.

Bowa was sitting next to Larry Hisle on the bench during an exhibition game at Jack Russell Stadium in Clearwater. Hisle said something that made him laugh.

“The next thing I know, Gene Mauch’s in front of me,” Bowa said. “He goes, ‘Don’t look up. Tell me what the count is.’ I said I had no idea. He said, ‘That’s the point I’m trying to make. You’re here to learn. Pay attention to the game.’ And from that point on, I was praying he would come down and ask me what the count was. He never did the rest of the time I was affiliated with him, but he got his point across.”

Even after establishing himself, making an All-Star team, and winning a Gold Glove, he never allowed himself to become complacent. Again, his father set the tone.

“I could very easily have said, ‘I’m the shortstop,’” he said. “But my Dad always told me that when you go to camp it’s not what you did last year, you’ve got to win a job again. So not one time did I go into spring training saying that. I went in thinking I had to win a job every year.”

He invented threats to his security that were highly unlikely or entirely made up.

“I wanted to play every day,” he said. “I didn’t want them to put me on the DL and then maybe call up some kid – because we had a good farm system back then – and maybe he goes 10-for-25 and they’re thinking, hey, this guy can play shortstop. We might be able to move (Bowa).’ It wasn’t that I was playing scared. It was just that I want this job, I like what I’m doing but I’ve got to earn it every year.”

And, yeah, he caught some breaks along the way.

His baseball career could have ended after he graduated from Sacramento’s McClatchy High School. But Del Bandy, the baseball coach at Sacramento City College, had seen him play American Legion ball and asked him to try out.

“I said, ‘Coach, I got cut from my high school team. How am I going to make your team?’ And he said, ‘I’m going to give you every opportunity to play.’ So I went out and I made the team and I made all-conference two years in a row,” Bowa said.

That attracted the attention of Phillies scout Eddie Bockman who recommended signing him even though, the first time he went to see Bowa play, he was ejected from both games of a doubleheader.

There was the moment at the end of spring training in 1969 when he was summoned to the manager’s office and offered a peculiar proposition. ‘I’d literally made the team. Bob Skinner was the manager and he said, ‘You’ve made the team, but you’re going to play utility. The only way this can change is if you want to go down to Triple-A and learn how to switch-hit,” he said.

“Nobody’s going to say they want to go to Triple-A. I said, ‘I want to go to Triple-A.’ I didn’t want to be a utility man. They looked at me like I was crazy.”

By the time he had made it to the big leagues as the everyday shortstop the following season, Frank Lucchesi, his manager at both Double-A and Triple-A, was the Phillies skipper. That turned out to be a bit of serendipity when Bowa ended May hitting .191.

Once again, he was called into the manager’s office. This time he braced himself for bad news. Instead, Frank told him that, no matter what, he would be in the lineup every day for the rest of the season.

“I walked out of there realizing that this man, who had waited so long to get a chance to manage in the big leagues, was putting his career on the line for me,” he said. “I thought, ‘I’ve got to do something, man.’ And hitting coach Billy DeMars. Things like that stand out. Guys who have that much confidence in you.”

He finished his rookie season with a .250 batting average.

Ten days after he informed the Mets that he planned to retire after the 1985 season, he got an out-of-left-field phone call from McKeon, offering him the opportunity to manage at Triple-A Las Vegas.

“There was a lot of luck involved. No question,” Bowa reflected. “I was lucky to not get (seriously) hurt while I was playing. And it means being in an organization that respects you and keeps you involved.”

The final point may be the most incredible element in this saga. At the end of the 1980 season, which ended with the Phillies winning the World Series for the first time in franchise history, Bowa had been promised a four-year contract extension by owner Ruly Carpenter. But Carpenter sold the team to a group headed by Bill Giles, who declined to honor Carpenter’s unwritten commitment.

The disagreement spilled into the newspapers. Bowa called Giles a fat liar. Giles fired back and eventually traded Bowa to the Cubs, throwing in future Hall of Famer Ryne Sandberg for good measure.

Fast-forward to 1989. General manager Lee Thomas wanted to bring Bowa back to be on manager Nick Leyva’s staff. Giles had to sign off on the move and did without hesitation.

He coached eight seasons with Leyva and Jim Fregosi but was let go when Terry Francona took over in 1997. The feeling was that the rookie manager might feel uncomfortable with a franchise icon figuratively looking over his shoulder. Bowa completely understood.

The situation was different the next time he was, as they say, relieved of his duties. He replaced Francona in 2001 and was dismissed with two games remaining in the 2004 season. This time, he denounced the decision loudly and publicly.

And yet. . . When Sandberg, now the Phillies manager, asked the organization to bring him back yet again in 2014 it led to Bowa 4.0.

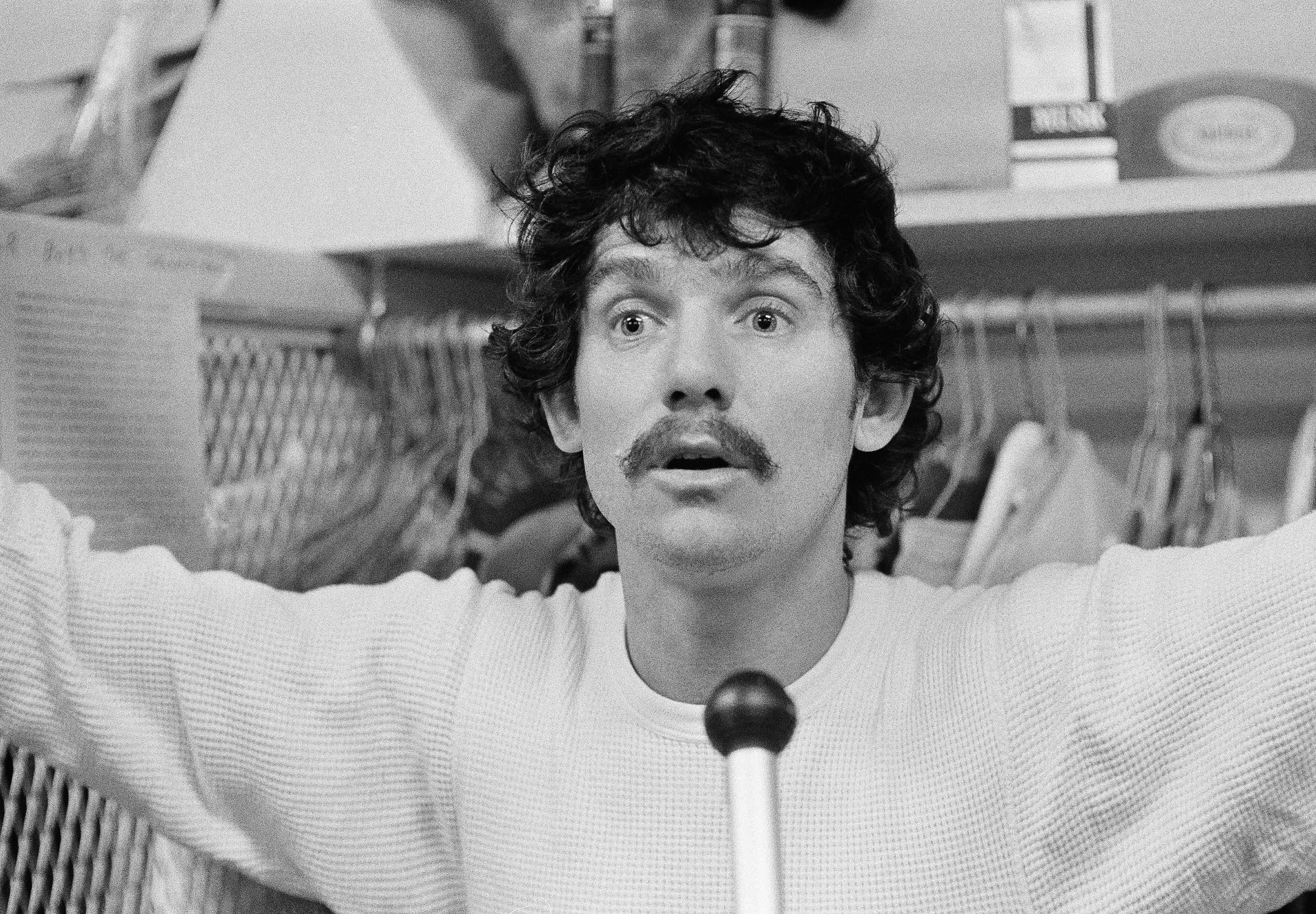

Explained club president Dave Montgomery at the time: “I think passion is what opens doors for Larry. And sometimes closes doors for Larry. Every time he left, there were still loads of people who respected him and were friends with him. I certainly think that anybody that’s known him has incredible respect for his knowledge of the game. That’s legendary. He’s remarkably current as far as knowing today’s players. That’s very unusual. Nobody eats, drinks and sleeps it more than Larry Bowa.”

By mid-afternoon, Gullifty’s was empty. Bowa was still talking baseball. Who was going to win the American League? The National League? Was there a dark horse most people were overlooking?

Most people mellow as they get older. Bowa, it must be said, seems to have at least resisted the impulse.

He will now admit to regretting some of his more outspoken comments about any number of people who aroused his easily provoked ire. “There were a lot of bad things said, mostly on my part,” he acknowledged in 2014. “As you get older you realize, ‘That was stupid. Looking back at it, it could have been done differently on my part.”

He conceded that he sabotaged his managerial aspirations because he unreasonably expected the players to work as hard as he did. More than that. To care as deeply.

Like the day, less than a week into his first Grapefruit League season as the Phillies manager, that the team’s record dropped to 2-3 after reliever Ricky Bottalico, a notoriously slow exhibition performer, was hammered in the late innings.

“We’d be 5-0 if it weren’t for your bleepity-bleep pitchers,” he snapped at pitching coach Vern Ruhle as the fans filed out of Jack Russell Stadium. That probably wouldn’t happen today.

But mellow? Hardly. The conversation that was coming to an end had been filled with unfiltered observations and tart opinions on all things baseball. The Phillies game had already been postponed, but that wasn’t a problem. Not with a smorgasbord of games to watch on television, especially the opportunity to switch back and forth between Rangers-Mariners and Astros-Diamondbacks late games.

“It gives me a rush,” he said. “I’ll be talking to myself. My wife (Patty) will ask who I’m screaming at. ‘Oh, just some stupid moves. . .’ I’m into it. It’s hard for me to separate that I’m not in uniform. The other night I got mad at a game (the Phillies) lost. Patty said, ‘What are you mad at?’ I said, ‘I can’t stand the way we played tonight.’ She said, ‘Are you kidding? You’re not even in uniform.’ But missing a cutoff man. Pitcher not backing up a base. Just little things.

“You get caught up in what you did and you expect everyone to do it. It’s not right. I know it’s not right. Everyone’s told me it’s not right. But I’m still saying to myself. . .”

Love of the game is one statistic the analytics crowd hasn’t been able to develop a metric for but it’s hard to envision anybody who has held baseball so close for so long. Asked what the term baseball lifer means to him, he barely hesitated.

“It probably means that I’ve been very fortunate because I don’t know what I would have done without baseball,” he said.

“Even to this day, as soon as Christmas is over, I think, ‘Oh, man, spring training is coming.” It’s embedded in your mind. It’s how you’ve lived your whole life. I look forward to that. I look forward to watching the kids in the minor leagues. I like doing that stuff. I really believe that when you’re around younger guys it makes you feel young and helps keep your energy level up.”

It’s time to leave the restaurant. Bowa slides out of the booth.

“Baseball has been my life. And I really believe I never woke up and said, ‘I don’t want to go to this game. I don’t want to go to spring training.’ It’s never come up. And when it does, I’m gone,” he said

“Maybe people say I was too hard on myself. But if I wasn’t hard on myself, I don’t think I would have played as long as I did.”