Can you give me sanctuary?

I must find a place to hide. . .

Can you find me soft asylum?

I can't make it anymore

The man is at the door

“The Soft Parade” / The Doors

SCRANTON, Pa. – This city of 75,000, tucked away in the northeast part of the state, was once hailed as the Anthracite Capital of the World. It’s now better known as the home of Dunder Mifflin, a fictional paper company in the hit sitcom “The Office.”

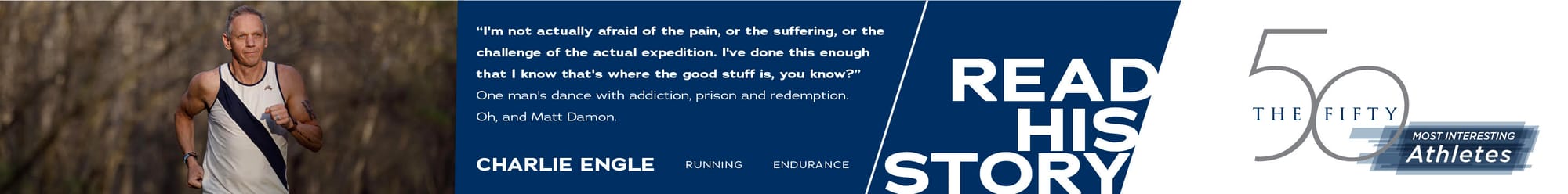

Lenny Dykstra lives here. On the ground floor of a two-story 1,050 square foot house that could charitably be described as a fixer-upper while he recuperates from a February stroke.

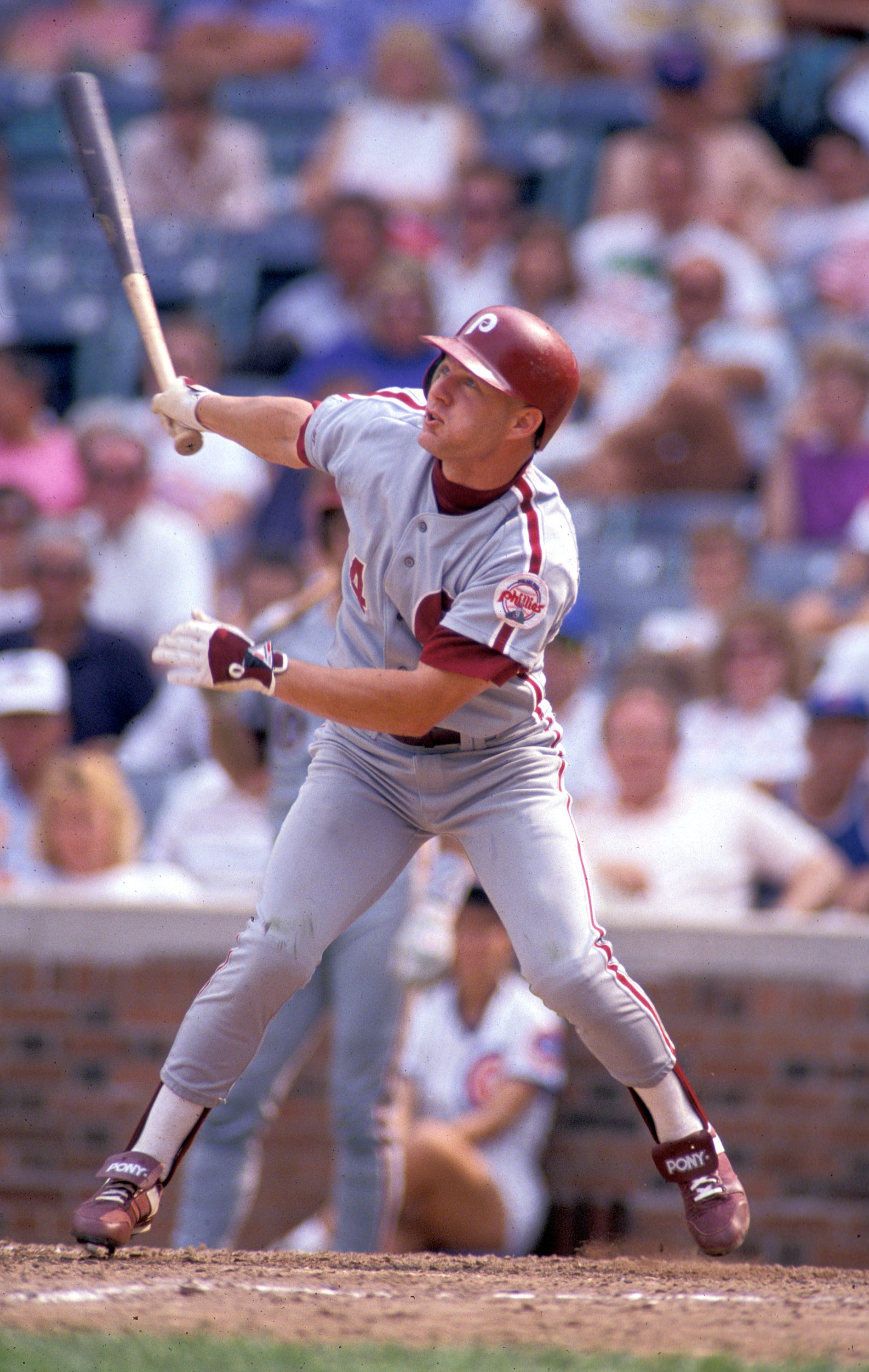

Lenny Dykstra lives here. Far away, physically and psychically, from the Southern California glitz and the New York City hustle and flow that were his natural habitats when he won a world championship with the Mets in 1986 and when he made three All-Star teams and finished second in the Most Valuable Player voting with the Phillies in 1993.

Lenny Dykstra lives here. In the shadows. Metaphorically because, unless they land a plum broadcasting position, most sports stars slip into the recesses of our consciousness when they retire. Also literally. The power and water are often turned off for lack of payment.

Lenny Dykstra lives here following a dizzying freefall from nearly unimaginable heights. “Temporarily,” he stressed to a recent visitor. “Temporarily, dude.”

Made enough money to buy Miami... But I pissed it away so fast... Never meant to last... Never meant to last

“A Pirate Looks at Forty” / Jimmy Buffet

Dykstra is 61 years old. He played his last big league game in 1996, forced to retire in part by spinal stenosis. Overall, he made an estimated $36.5 million playing baseball for a living.

In 2008, his net worth was reportedly $58 million. He was living in an 8,000-square-foot mansion in Thousand Oaks, California, which, even then, was worth $5 million. It overlooked the exclusive Sherwood Country Club where Tiger Woods and former President Gerald Ford were members. He owned a string of successful car washes and a private Gulfstream jet. He drove a $300,000 powder blue Bentley.

In July 2009, he filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. He listed $50,000 in assets.

If there was one trait that defined him as a ballplayer, it was that he was never satisfied. That inner drive that allowed a skinny, undersized 13th-round draft choice to exceed all expectations except his own. In the end, it was that same bulletproof bravado that helped fuel an almost too-bad-to-be-true financial plunge. Those close to him have a shorthand explanation to pinpoint the fork in the road.

The Gretzky mansion.

As spectacular as Dykstra’s home on Ladbrook Way was, the nearby house of the NHL Hall of Famer Wayne Gretzky on Newbern Court was even bigger, even more opulent, even more expensive. So, of course, he had to have it.

To make it happen, he sold the car washes; the buyer defaulted. He took out a convoluted series of loans; he said the banks changed the terms. He might have been able to sell the new property to extricate himself, but the housing market had cratered by then.

Everything that followed started there.

The bankruptcy. The divorce from his wife Terri, during which he signed away his Major League pension. The accusations that he had lied about improperly hiding and selling assets. The federal fraud charges. The arrest for grand theft auto. More than six months in a federal penitentiary. Twenty-five state counts, including drug possession.

He insisted there isn’t one thing he regrets, nothing he’d do differently now if he had a do-over. “Not really,” he said. “I made mistakes. A lot of them. But in baseball, you learn to accept failure.”

So he started drinkin’... Took things that messed up his thinkin’

“The Blues Man” / Alan Jackson

To be clear, Dykstra was never a saint. Even at the peak of his career, he barely bothered to hide his indiscretions. He drank, he smoked, he womanized. And he made it clear that he would ingest any substance he thought would enhance his performance. Or heighten the pleasure of party time. Or recover from the aforementioned party time.

Then, the cycle would repeat. Day after day after day.

Baseball players have a small window to get their money, he’d point out. Gotta make all you can while you have a chance.

Given his unrepentant lifestyle, it’s probably not surprising that he had the stroke. Still, it dramatically raised the degree of difficulty of his already complicated existence. He has no feeling in his right hand and can’t lift a cup or glass. His speech is slurred, although it’s difficult to know if that’s all health-related or exaggerated because he’s lost his dentures again.

But that’s not the worst part, he said. The worst part is that he’s no longer able to have sex. Although his explanation was far more colorful and colloquial each of the many times he brought the subject up.

I have lived, life in the fast lane... You gotta watch your back... And look both ways

“The Dirt Road” / Sawyer Brown

Knock, knock. No answer. Knock, knock. Finally, Dykstra came to the door. He seemed startled even though the meeting had been prearranged. He had a neatly trimmed beard and seemed to be in decent shape. But he shuffled when he walked, which made him appear at least a decade older than his chronological age.

He asked if I could come back in a half hour.

Full disclosure: I’ve known Lenny since he was traded from the Mets to the Phillies in 1989. I covered his entire career for the Philadelphia Daily News until he retired, and we stayed in touch periodically after that.

We had a good working relationship. He alienated a lot of people in those days, though, people who may well be experiencing a deep sense of schadenfreude now. He could be difficult, dismissive and crude.

At the same time, he had a certain quirky charm — an impish gleam in his eye. A boyish delight at all the world had to offer and an unquenchable desire to gobble up as much of it as he possibly could. He was endlessly interesting. He was great copy.

So when posts began to appear on X (formerly Twitter) this summer asking for someone to donate a full-size bed, to volunteer to give him rides to and from autograph shows, to pay to share a meal with him, it came across as desperate and sad. He now says those pleas were posted without his knowledge by a friend who mistakenly thought he’d appreciate the outreach.

I felt sorry for him despite being acutely aware of the negative headlines that had hovered like a dark cloud over him for years. Unsavory allegations involving a housemaid, a teenage girl, an escort service. Stories about confrontations with an Uber driver that involved a gun and drugs. Late-night orgies so loud the New Jersey neighbors called the police. Reports that he had stolen sheets and pillowcases from a luxury hotel. Again, he denied all wrongdoing.

His support group today is small and eclectic and includes a guy who befriended him and is trying to help him fix up the house and whose wife brings him dinner a few times a week. A local chaplain who stops by regularly to check up on him. A woman in California he’s known for years who tries to help in any way she can. A Los Angeles attorney, Matthew Blitt, who owns the house he lives in and allows him to stay there rent-free. Some of his former Phillies and Mets teammates wonder among themselves what they can do to help.

I called and proposed a story to try to spread the word that he could use some assistance. I also sent $200. But when I walked away after spending a couple hours with him, it was pretty clear he wasn’t yet ready to admit he’s going to need a lot of help to figuratively get back on his feet.

He said he rarely drinks or smokes anymore, although he does vape. He said he hasn’t done any physical therapy since he left the hospital. He claimed he doesn’t take his meds because Viagra doesn’t work for him, so he doesn’t believe the other prescriptions will, either.

So he hasn’t lost his dry sense of humor. At least, his inner circle hopes that’s a joke. That he’s taking the drugs he’s supposed to and staying away from ones the doctor wouldn’t approve of. They hope, in short, that he’s taking at least minimal care of himself. But they have no way of knowing for sure. They’ve been fooled before.

There's bound to be rough waters

And I know I'll take some falls. . .

I'll never reach my destination

If I never try

“The River” / Garth Brooks

During an hour-long conversation, Dykstra occasionally lost his train of thought. But he repeatedly kept finding his way back to a pair of related themes.

First, he may be down, but he’s not out.

“I look at it like, yeah, I had a stroke. But I made it,” he said. “It came out of nowhere. It was weird. You don’t feel any pain, really. But I’ve rebounded well. It could have been worse. I’m lucky. I can still walk. I can still talk. I could have died. Look at people who’ve had strokes. You know what I mean, bro?

“It’s been rough. But I always try to look at things positively. I’m not saying, ‘Oh, poor me.’ I look back and learn from it, but I don’t live there. Most of my life, I’m thinking about the next thing I’m going to accomplish.”

Which leads to his second recurring motif. He’s already plotting his comeback.

“I’m going to do a (variety) show. It’s going to be called ‘Different Strokes for Different Folks.’ Cool name, right? It’s going to be awesome,” he said. “That’s how I roll. When I do things, I do things big.

“I’m going to help people. I never wanted to. Well, I mean, I wanted to help people. But the main person was me. When I was in the hospital, all the patients were miserable. Miserable. They’d had strokes. They have nothing to look forward to. When you’re one of them, they treat you different.”

All the details haven’t been worked out yet, he conceded. But the outline is that entertainers would put on a monthly show that would be offered to stroke survivors only on a subscription basis. It would cost $200 a month. Maybe insurance would cover the cost.

Honestly, it sounds beyond far-fetched. Fantastical. Dykstra was a terrific hitter when behind in the count, but the challenge he’s facing now is much steeper than simply being down 0-2. He’s beaten the odds before, but nothing as daunting as this.

At the same time, he returned over and over to the thought that stroke victims have nothing to look forward to. If nothing else, this gives him something to get up for in the morning.

There’s still at least one more verse to be written in Dykstra’s song of life. For better or worse, for richer or poorer, he’ll be the one to compose it.