As Maria Laborde recounts the necessary steps for her defection from Cuba, it feels as though she’s reading from a John le Carré novel. There’s a definable plot, some humor and a satisfying conclusion. As she relays her journey, her English is wrapped tightly in a thick Cuban accent, and she’s a naturally fast talker, for which she unnecessarily apologizes.

Her story involves deceiving a Cuban security services agent assigned to watch over the national team during an international trip. Then there’s a cab that drives her to meet her first contact, who helps her catch a flight where a second cabbie refuses to get near the border with a Cuban as a passenger. There are four more goose-bump-inducing, harrowing, page-turning chapters in this based-on-a-true-story-because-it-is plot.

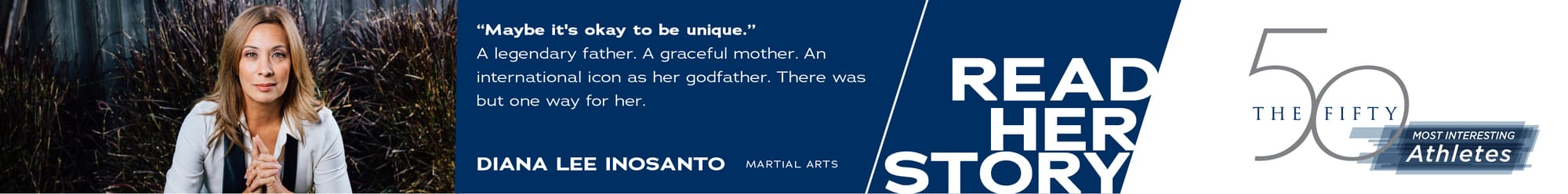

Maria was almost guaranteed a spot in Rio's 2016 Olympic Games representing Cuba. [Courtesy IJF]

But before we get to the spoilers, we need to understand why she was defecting in the first place. At this moment in her personal timeline it’s 2014 and she’s widely viewed from the outside as one of the most successful Judo competitors in the world. Her natural aggression and thirst for physicality put fear in opponents and has been the main driver of her life story.

Where those violent tendencies come from is understandable when you learn about the silent rage she lived with as a young girl, when her mother passed of cancer when Maria was 11. She released that pain and anger on other kids on the playgrounds and streets of Guantanamo City.

Fighting was her means of coping, and it took a savvy grandmother charged with her care to channel that pain into something positive.

“My grandma was tired of me. Literally, I fight every day in school. But this, that's my big deal, okay? You fight every day, that's like okay, you just get in trouble. They call your parents. But it's like finding that normal. No big deal.

“I was angry because my mom passed away. My mom was my biggest supporter. Unfortunately, my mom passed away. I don't see her anymore. I was really angry with life. I'm like, ‘Why?’ And then I had to fight every day to release my anger.”

Fortunately for Maria and her grandmother — her father was involved and served in the Cuban military — communist Cuba operated much like the old Soviet Union. They presented opportunities for kids to identify who was good at what. In elementary school, specialty sport coaches would visit and introduce the kids to their program, and invite them to try it for free. This is how Maria was introduced to judo.

“My grandma say, ‘You cannot keep doing that. I know you have to do something to be able to relieve your anger. You can’t keep going like this.’”

After the demonstration at school, her grandmother took her to the free clinic and saw the potential value in having Maria pummel kids in a controlled environment. Coaches quickly identified her potential. Within a week she was competing in a regional tournament, where she won a gold medal. Two months later she went to nationals, where she won silver.

Judo was now presenting Maria with a path she could see.

“I learned how to take a loss. I learned how to enjoy when I win. I started to get better and I just had to be happy again,” she says.

Success meant she was valuable to the Cuban government. She — and other athletes like her — was proof that the communist system worked. Look at our success in baseball. Watch Maria dominate in judo. The trade-off for Maria was a material loss of control for decisions that involved her life, her future and her mental well-being.

She aspired to be a doctor, and for the first year after high school she attended the “doctor university.” But when the national team called, everything changed.

“They said that my career is for the government, for the institution,” she recalls. “They had to do everything. They changed my career to physical education because in the national gym you cannot be a doctor.”

In this competition timeline, she is approaching the 2016 Rio Olympics. She is the third ranked judo fighter at the time, with recent wins in the 2014 World Championships (bronze), the Pan American Games (gold), and the Grand Slam of Paris (bronze) and she’s a multiple-time national champion of Cuba.

Despite her stature as a world-class athlete, decisions are being made for her. She saw other Cuban athletes with more impressive credentials than hers being poorly compensated, poorly fed and not having the training tools necessary to remain elite. She refers to one Olympic champion who was being paid $300 per month.

Maria was paid $50 per month as a “reward” for being a bronze medalist at Worlds.

“You have a hard time with everything in Cuba,” she says. “You want a better life? I asked myself this and I say, ‘Well, I can. I want to have a better life.’ I don’t want to have this kind of life.

“I was doing well. I liked the pressure but it’s complicated. Your coaches are really demanding and they don’t care about you. Sometimes you feel like you cannot handle any more. In my mind, I didn’t want to be there anymore.”

She spoke of excruciating four-hour workouts that ended with no water to hydrate, to shower. Days when there was a single meal. It wore her down. She kept using the word “complicated” to describe her life as one of Cuba’s best athletes.

And that is how she knew, even with the Olympics in her grasp, there was something better for her out there in a world she hadn’t seen. Until she made the national team, Maria had never left the country.

Ironically, that’s how she found her window to escape.

In 2014, Maria traveled with the Cuban national team to the Central American Championships in Veracruz, Mexico. This would be her final competition for her homeland.

Like boxing, judo has a pre-event weigh-in. Athletes take their passports for identification, get weighed to verify the class they will fight in and then compete. In Cuba, the communist regime sends state police to “look after” the athletes. Often they are using intelligence operatives from the DGI, Cuba’s version of the Central Intelligence Agency. Upon arrival, the agents confiscate passports to avoid exactly what Maria was planning.

Maria says she normally turned in her passport after weigh-ins, but this time she didn’t. And fortunately for her, nobody noticed.

After winning a gold medal in the event, Maria left her hotel. This was the moment she had planned for. If she could get past state security, her chances were good.

“I told my roommate I was going to go,” Maria says. “I told her you cannot tell anybody because I had to do it in secret. Nobody can know.”

As she exits the hotel, the state security agent stopped her and asked where she was going. Her first instinct was to tell him she was going for a run. Thinking on her feet, she pivoted to “I’m going to a competition.”

He bought it, and when he turned his back to Maria, she slipped into a taxi. The most dangerous step was now complete. The taxi took her to a waiting friend.

“My friend was waiting for me and he booked my trip (to the border). It was really, really easy to get there. But what’s hard for me was I made this decision to leave everybody behind.”

Maria wasn’t just leaving the national team, she was defecting from her home country. She was leaving her family behind as well.

“It was tough, especially for my father, my grandma, they are really attached to me.”

In Veracruz she boarded a flight to the border town of Reynosa, across the muddy brown waters of the Rio Grande River from McAllen, Texas. Her friend had made all the arrangements. When she landed, the plan was to take a taxi to the border. This provided her first true test of whether she could make it out.

When she entered the taxi and told the driver where she wanted to go, he quickly identified her as being Cuban and refused to take her, worried for himself about what might happen.

Her only other option was a bus, which she had learned about while talking with some locals on the plane. The bus made her more vulnerable, and she was scared. But this was now her only way to the U.S. border.

“It was really very scary. It was just me and the bus driver alone. If something happens there’s nobody to save me. Nothing happened. The goal was to go for it, I just got to get to the border.

As she stood inline with others waiting to speak with border agents, it all became real. She knew she had to request political asylum — those were the magic words she must say.

When she was second in line, the man in front of her was pleading with border agents to let him in. He wasn’t using the right phrases, she said, and did have a passport. Laughing, she recalls how she and others in line were whispering instructions to the man. This went on for 20 minutes before he was turned away.

WIth nobody between her and the border agents, she meekly approached and identified herself, showing her passport, and spoke the words.

“I want to apply for political asylum.”

U.S. officials interviewed her and detained her nearly five hours. She had arranged for a friend and former Cuban athlete — another defector — to meet her in Texas. And with that, her life in Cuba was behind her, and her athletic career ended without having competed in the world’s biggest showcase — the Olympics.

What came next was even harder.

“I didn’t have family. I didn’t drive. I didn’t know how to use technology. I didn’t speak English. I suppose it’s like being a baby. Now I had to grow up.”

Still in her early 20s, Maria sought to put a life together. It wasn’t easy. She looked into whether she could compete for the U.S., but without citizenship that was a dead end. She found jobs teaching judo, working for different clubs and offering seminars and training camps.

“But I didn’t really want to be doing that.”

After living in Houston for a while and later coaching in Dallas and Fort Worth, she migrated north even though she wasn’t a fan of colder temperatures. There was a stop in Illinois before she arrived where she lives today, in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Years crawled by. She was feeling unfulfilled. Yes, she had all the freedoms Cuba denies its citizens. But teaching only reminded her how much she missed competing. She began work toward gaining citizenship, and as that process moved forward she began competing again. She earned her U.S. citizenship in 2021.

Maria entered some tournaments where she earned $1,000 to compete. “For me it was easy; for others it may have been hard.” But the money, to her, was too easy to turn down. Ironically, this is where her current coach took notice.

Her coach, Jhonny Prado, saw her at events and encouraged her to consider a comeback. Her psychologist, Fanmy Vega, agreed. Fanmy happens to be Prado’s wife.

“She was my psychologist in Cuba on the national team and later they got married,” Maria says. “She talked to me about coming back and I said I didn’t want to, I want to get this $1,000. I don’t want to do it.”

Eventually, the couple persuaded Maria to compete in an event in Tunisia with the ultimate bait: see how you do, then decide.

“So I got a gold medal there and I’m like, ‘Oh, okay!”

She continued to train and compete, paying her own way at first until he was able to earn a spot with USA Judo. Finally, eight years after Rio and ten years since she defected, she qualified for Paris 2024.

Although she didn’t medal, she took great care to enjoy the Games for the spirit in which they are intended. Walking the village, she saw familiar faces like Simone Biles and LeBron James.

“I just tried to relax and enjoy it.”

Now, she is taking time off before resuming training near the end of the year. Her next goal is to qualify for Los Angeles 2028.

As our call comes to a close, she tells me that within days she is heading to Cuba to visit her family. It’s been 10 years. The pitch in her voice gets higher and — if this was even possible — she is speaking faster, the joy is palpable through our wireless connection.

“I am so excited. I’m excited to see my grandma. And she’s so happy. She’s already fixing everything in my room and has all the plans already. My father is so excited. He will pick me up with my uncle.”

I ask Maria if she’s worried about the Cuban regime as she returns home. Defection has become commonplace among Cuban athletes, where more than 800 have not returned from international competitions in the last decade. She let’s out a long “ehhhhhhhhhhh” and she laughs. Cuba enacted a law in 2013 that allows high-profile defectors to return for visits after eight years away.

Still laughing, she adds, “I think I’m good. I’m good. When I get to the airport we’ll see if I get in. If they don’t let me in, then it’s a problem.”