There he stands ever so tall at the front of the room, a commanding presence in the wake of a group of athletes hanging on to his every word. The loud hum of the air-conditioner nearly drowns out his raspy pre-game speech.

“Tonight, it’s all about being disciplined, fellas,” Michael Bishop tells his team. He’s an imposing presence in the room, his linebacker build accentuated by his broad shoulders that give way to his large hands that could crush a football with one tight squeeze. “The most disciplined team is going to win the game.”

This rag-tag up-start charter team he leads has reached the pinnacle of high school sports in his two seasons. They’ve done it without a home stadium. Their football field is a mix of grass and dirt — worsened by the brutal Texas summer — and aluminum stands that seat no more than 70 people.

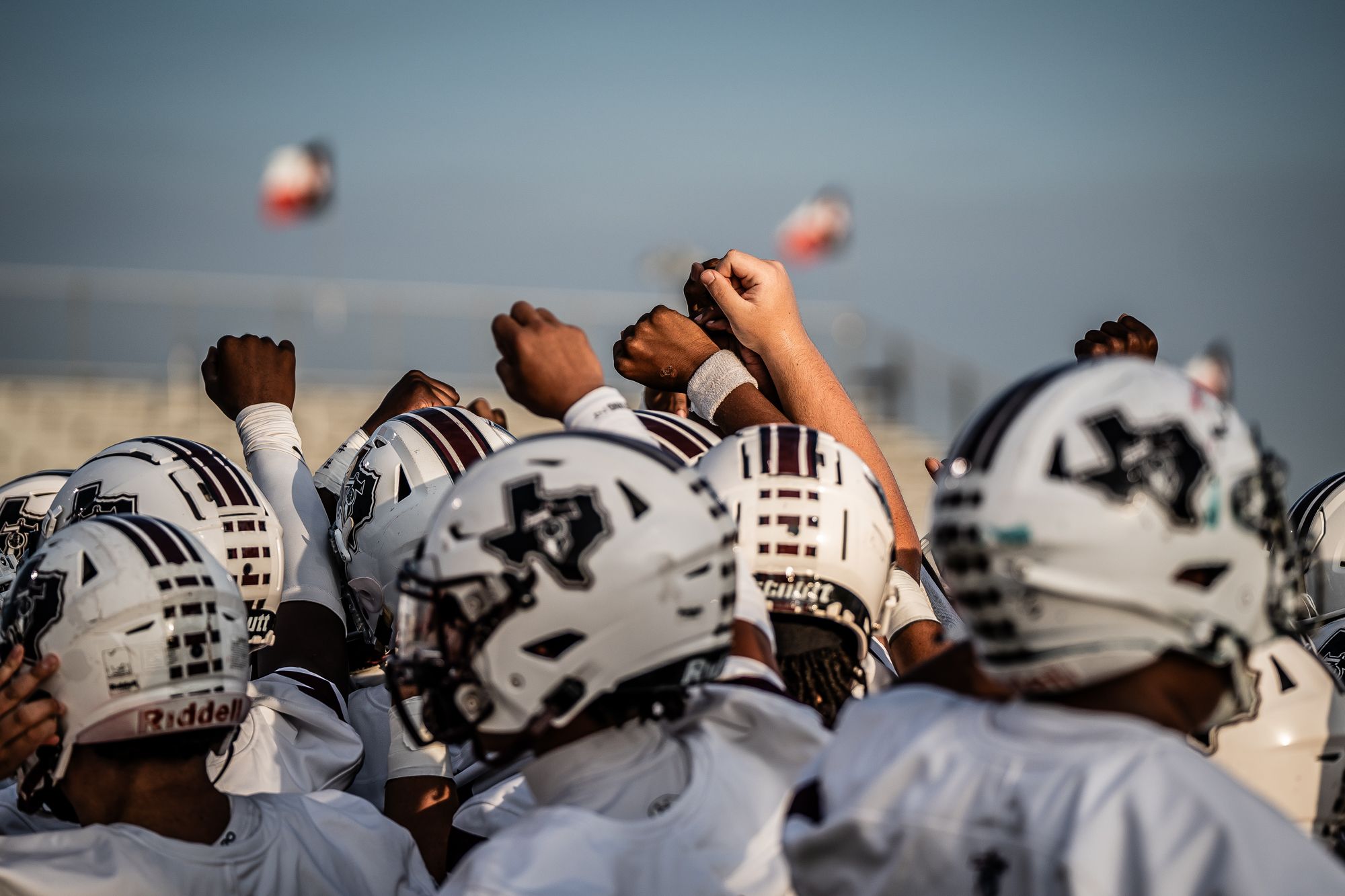

Bishop's Legacy School of Sports Sciences team takes warmups for the first game of the season. [Matthew Fults photos]

They play all their games on the road, in towering high school stadiums that seat thousands — everything is bigger in Texas, after all — with dual locker rooms and three-story press boxes that give total views of the all-turf fields.

None of that matters here at the Legacy School of Sports Sciences, where this group of determined players walk into those big-money schools with their flashy fields and flat-out dominate. The Titan football team has multiple Division I signees. And this year’s team of 14- to 18-year-olds are hoping for a third-straight state championship, cementing themselves as one of the best charter programs ever.

“We’ve got one common goal,” Bishop says. “What’s our goal for tonight?”

“To dominate,” one says.

“To win,” says another.

It’s a Friday night and their season opener against Huffman Hargrave, a large school with one of those decked-out stadiums. They also beat the Titans by one point to open the season last year. Bishop runs through the game plan a final time. The players are focused as he speaks, offering a “yes sir” and “no sir” when warranted. To the seniors, Bishop says, “This is your last first game of your high school career. Make it count. Leave nothing on the field.”

There’s something to be said for having a high school coach with the career and accolades that Bishop carries. He was the best college quarterback of his time, so talented in dismantling defenses with both his arm and legs that he made it look easy. Now, he’s taking his decades of experience to coach high school athletes who one day hope to reach the heights he once ascended.

The football zips through the air at lightning speed, past the 40-yard line … soaring over the purple Wildcat logo that dons midfield at Kansas State University’s football stadium … over the heads of defenders at the 40 … the 30 … the 20 … the 15 … and into the arms of wide receiver Darnell McDonald who snatches it out of the air and runs it into the end zone for a KANSAS STATE TOUCHDOWN!!!

“Unbelievable throw by Michael Bishop!” bellows a TV announcer as the Wildcats quarterback speeds down the field to hug his receiver. “That ball must have gone 70 yards in the air!”

There’s Michael Bishop again, in his purple-and-white Kansas State uniform taking a snap under center. He drops deep, scanning the field for an open receiver, but he sees an opening at the line of scrimmage. Bishop tucks the football and runs for the hole, bounces right past a linebacker and turns on the jets to the 10 … the 5 … past a diving defender and into the end zone for another KANSAS STATE TOUCHDOWN!!!

“K-State will run a lot of quarterback draws out of all different looks, out of all different formations,” says another TV announcer. “They want to utilize the ability of Michael Bishop to be a great running back. And Michael Bishop just showed the speed to get outside after breaking through the line and turns it into a K-State touchdown.”

Now, there’s Michael Bishop in a New England Patriots jersey, swapping the collegiate purple of K-State for the professional blue of New England. There’s three seconds left in the first half, the Patriots trailing the Indianapolis Colts, 10-3, and New England has the ball at the Colts’ 44-yard line. Bishop takes the snap from the shotgun, drops back deep, and catapults a football into the end zone, where receiver Tony Simmons leaps above the defenders for a NEW ENGLAND TOUCHDOWN!!!

“Unbelievable!!!” shouts announcer Vin Scully as Bishop mobs Simmons in the end zone. “What a way to end the half!”

Michael Bishop’s highlight reel is a captivating montage of awe-inspiring, head-scratching, jaw-dropping plays of a quarterback zipping and zagging, juking and jiving, and throwing bombs and making plays in ways that quarterbacks flat-out didn’t make at the time. He was, by all accounts, the best quarterback in college during his time, amassing a 46-3 record in four years and winning two national championships at Blinn College and nearly another at Kansas State.

“That was probably the greatest attribute Michael had,” says Bill Snyder, Bishop’s head coach at Kansas State. “He had the capacity to be both a running and throwing quarterback. He is an extremely talented, gifted athlete who possesses a great deal of confidence.”

For all his success in high school and college, Bishop’s style of play didn’t translate into a National Football League that, at the time, focused heavily on quarterbacks serving as field generals who dissected defenses with their arms and not their legs.

Which begs the question: Was Michael Bishop a pioneer who was too good for his time?

Bishop is a product of Texas. And in Texas, football is king. Across the state, towns big and small shut down early to gather under the Friday night lights. Businesses paint their windows in big, bold letters supporting their local team. Convoys of cars travel to away games, no distance too far. It was no different in Willis, a rural community an hour north of Houston where Bishop called home.

“To be part of a small town is amazing because they all come together for one reason: to watch Friday night football,” he says. “I lived for that moment.”

Bishop grew up in a large household with six siblings who loved to compete. Who can stay up the latest? Who can get up the earliest? Who can be the first in the shower in the morning? But for all the competition, there was a mutual understanding: support one another and push each other to be their very best.

They had a great support system in their parents. Their dad, Artis, left for work every morning at 4:30 so he could be home in time for their games. Their mom, Ethel, worked in education and stressed the importance of good grades. Above all, Artis and Ethel instilled in their kids: “If you’re not a champion, you better be doing everything you can to be a champion.”

Bishop was a two-sport athlete in high school, replacing his fall football pads with a baseball glove in the spring. He had dreams of one day donning the burnt orange for the University of Texas Longhorns and, hell, maybe even one day suiting up for his dad’s favorite team: the Dallas Cowboys.

Even in high school, Bishop’s talent shined. He joined varsity his freshman year and took the reigns as starting quarterback as a junior. David Sine, an assistant coach in charge of quarterbacks, often warmed up with Bishop before games. All these years later, he can still feel his hands stinging from Bishop’s passes.

“I’ll tell you this,” Sine says, “I was so happy when individual warm-ups were over because my hands hurt. That kid had a bazooka.”

Michael Bishop poses at Legacy School of Sports Sciences. [Matthew Fults photos]

During one game, coaches called a quick swing pass to a tight end at the line of scrimmage. But Bishop had his own idea. After taking the snap, he aborted the pass and rolled out as coaches yelled at Sine about the blown play.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh shit! What the hell are you doing, Michael?’” Sine says.

Ever the playmaker, Bishop was never one to let his coach down. He launched a 70-yard bomb to a receiver in the end zone for a WILLIS WILDKATS TOUCHDOWN!!!

Suddenly, the coaches weren’t yelling What are you doing, Mike?!!! They screamed Thattaboy, Mike!!! as the sideline exploded with excitement.

It wasn’t just excitement that permeated throughout the field; Bishop provided a spark that electrified his small town. In his junior year, he led Willis to the playoffs. His senior year, he took the Wildkats to the state quarterfinals — two games shy of a Texas state championship.

“We were kids just playing football and didn't really realize that we lit a spark in the city,” Bishop told a Houston TV station years ago. “We gave the locals something to cheer about and be proud of. We really didn't know how much it meant at the time."

Bishop was heavily recruited by Division I football programs, but nearly every coach asked him to switch positions to either wide receiver or defensive back. Bishop was adamant: No, he was a quarterback.

The 18-year-old had another decision. As talented as he was on the gridiron, his talents equally shined on the baseball diamond. He was a multi-position player with a cannon of an arm who hit .418 for his high school career. The Cleveland Indians drafted him in the 28th round of the 1995 Major League Baseball draft.

Bishop held true to his beliefs. He stuck with football and rather than accepting a Division I offer and a new position, he signed with Blinn College, a two-year junior college in nearby Brenham, as a quarterback.

It was time for collegiate football to learn the name Michael Bishop.

Brenham has a similar vibe to Willis: small Texas town off a major highway — blink and you’ll miss it — that loves its football. The Brenham High School football team is a town favorite, but Blinn College has its own rich athletic history, with 44 national championships since 1987.

The football team owns four of those national championships and features notable alums like Cam Newton, Quincy Morgan, and Khiry Robinson.

On a campus filled with Division I hopefuls, Bishop broke through and became a household name with his run-and-gun style that captivated the town and led Blinn to back-to-back national titles. In his two years with the Buccaneers, Bishop finished a perfect 24-0.

Once again, the Division I offers flooded in. Once again, coaches asked that he switch positions.

But there was something about Kansas State coach Bill Snyder’s approach.

Kansas State was one of the first Division I programs that invested heavily in community college players. When Snyder met with Bishop’s family, he stressed the importance of an education above football — a blessing to Ethel. Admittedly, it drove the young Bishop crazy.

“For three hours, they never mentioned football,” he says. “I’m young. I’m thinking, ‘When are we gonna talk about football.’ But I trust my mom, so I said, ‘I’m going,’ even though I’ve never been to Kansas.”

Snyder took over the Wildcat football program seven years earlier and brought in an offense focused on quarterbacks who can both run and pass. Sound familiar?

“Michael fit that mold perfectly well,” Snyder says, referring to his offensive style as the quarterback run game. “Very few were invested in it. And that’s what prevented Michael from being attractive to other schools.”

Snyder was part of a coaching staff that created the quarterback run game back in the 1970s under head coach Hayden Fry at North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas).

For all the success Snyder had with his offense, Bishop’s speed, elusiveness, and arm strength took it to another level, regularly exploiting the best Big 12’s defenses. Bishop carried the Wildcats to an 11-1 record — the team’s lone loss was Bishop’s first since high school — and a trip to the Fiesta Bowl against the future NFL great Donovan McNabb.

Unlike Bishop, McNabb was a quarterback who fit the mold of a field general for the time: tall and strong enough to stand in the pocket with the accuracy to pick apart defenses with his arm. That made no difference to Bishop, who beat McNabb in a skills competition days before the big game. After the challenge, Bishop says McNabb told him, “You may have won this, but I’m going to win the big game.”

Bishop's squad takes the field, looking for a third-straight state championship season. [Matthew Fults photos]

“I stuck that in my mind the whole week of practice,” Bishop says. “I remember the coin toss. I looked him in the eye and I said, ‘Well, here’s the big game.’”

The result: Kansas State beat Syracuse 35-18.

Bishop threw for 371 yards and four touchdowns while rushing for another. He was named the offensive player of the game.

Kansas State had marginal success in its 86-year history, but with Bishop leading Snyder’s offense, the team’s time at the top had finally arrived. The Wildcats entered the 1998 season ranked sixth in the nation with Manhattan, Kansas, and the Wildcat faithful full of national championship hopes. Don’t tell that to coach Snyder, though, who focused on keeping the hype out of the locker room.

“Do the things that will allow you to be your best and the rest will take care of itself,” Snyder often told his team.

The Wildcats dominated the first nine games of the season, outscoring their opponents 472-69, en route to a perfect record heading into a showdown with their fiercest rival: the Nebraska Cornhuskers.

Kansas State hadn’t beaten Nebraska, one of the top collegiate programs in the country, in 30 years. The Cornhuskers were the defending national champions coming into KSU Stadium, having trounced the Wildcats the previous season, 56-26, a loss that Bishop admits still made him angry. As Bishop’s father, Artis, told Sports Illustrated back then, “It seems like he gets mad and plays better.”

And so, an angry Michael Bishop stormed into KSU Stadium determined to end the team’s dreadful curse against Nebraska and prove that Kansas State was the real damn deal.

Bishop struggled early, losing three fumbles in the first half, one with the game tied and the Wildcats threatening near the goal line. Nebraska held a 17-14 halftime lead. Angrier than ever, Bishop was relentless in the second half, connecting with receiver Darnell McDonald for two KANSAS STATE TOUCHDOWNS!!!

The curse was broken. The Wildcats beat the Cornhuskers, 40-30, as cheering fans rushed the field. Bishop and the team lost in a mob that famously tore down a goal post and carried it through downtown Manhattan.

“That was an amazing feeling for me,” Bishop recalls, “and it was an amazing feeling for the fans of K-State football.”

Bishop plopped onto a couch in Snyder’s office after the game, telling a Sports Illustrated reporter he was “a little sore.”

"I was getting hit on every play, whether it was a pitch or a pass or a run,” he said. “I don't know if they were trying to take me out of the game or intimidate me, but they were hitting me."

With the win, the Wildcats clinched the Big 12 North for the first time in program history and inched one game closer to the national championship.

After handling Missouri to end the regular season, Kansas State entered the Big 12 Championship against Texas A&M with a clear path to the national championship game. All they had to do was win

Bishop is both the head football coach and the director of discipline at the Legacy School of Sports Sciences. As the latter, he focuses more on correcting bad behavior than punishing students. It’s no more apparent than the day after a come-from-behind victory by the junior varsity football team.

What’s the big deal with being one minute late to class or one minute late to practice? A lot can happen in a minute. Without that extra minute on the field, the JV team never would have completed its comeback.

“I get a chance to tell kids the true experience,” Bishop says. “I’m not a high school coach who says watch this film or read this book. I was in the fire. I tell my kids all the time, ‘You can’t tell me how hot the fire is if you’ve never been in it.’ I’ve been in it. I’m right in front of you guys. I’m telling you the right ways.”

Although Bishop is years removed from his playing days, he can still feel the heat. None more so than the Big 12 Championship game against Texas A&M. So close Kansas State was to the national championship game. How quickly giants can fall.

Legacy School of Sports Sciences starts fast against the team that beat it last season. [Matthew Fults photos]

The top-ranked Wildcats entered the game a seventeen-and-a-half-point favorite. And with UCLA’s loss to Miami, Kansas State had a clear path to the national championship game. With a 27-12 lead entering the fourth quarter, it seemed all but certain the Wildcats would secure their spot.

Yet the Aggies, led by future Hall of Fame coach R.C. Slocum, mounted a fierce comeback in the final quarter, capping off a 15-point deficit with a touchdown and two-point conversion with a minute to spare that sent the game to overtime.

There, Texas A&M running back Sirr Parker found the end zone in double overtime, stunning the Wildcats and shattering their national title hopes.

“Man, that still stings,” Bishop says today. “That’s the one thing I didn’t achieve. I wanted to bring a national championship to Kansas State. And we fell one game short.”

Tennessee went on to beat Florida State, 23-16, in the national championship. Given the chance, Bishop says he has no doubt his Wildcats could have beaten either team.

“We had the best team in the country that year,” he says. “We just had a bad game.”

Though the loss hurt, the awards poured in for Bishop. He won the Davey O’Brien Award, reserved for the best quarterback in college football, joining the ranks of Peyton Manning, Troy Aikman, Andre Ware, and Steve Young. Bishop was the runner-up to the Heisman Trophy, second only to University of Texas running back Ricky Williams.

The New England Patriots drafted Bishop in the seventh round after that season. He sat behind famed quarterback Drew Bledsoe, the epitome of what professional coaches wanted in a man leading their offense: a drop-back passer who was prolific in the pocket. Bishop’s run-and-gun style never translated in the NFL and his playing time with New England was limited. Bishop says Patriots offensive coordinator Charlie Weis once told him, “You’re too talented; we don’t know how to use you.”

Bishop played in eight games in the NFL, completing 3 of 9 passes for 80 yards with one touchdown and one interception.

The next year, the Patriots drafted Tom Brady in the sixth round. Bishop says he and Brady became close during the 2000 season. At the time, Bishop was ahead of Brady on the depth chart. The two hung out after practices, sharing stories about how coaches told them neither could play quarterback. They would tell one another, If you get your chance, don’t ever give it back.

Bishop never got his chance in the NFL and was cut by the Patriots after the 2000 season. He spent 10 years in the Canadian Football League with various teams, where he won the 2004 Grey Cup with the Toronto Argonauts.

Brady, meanwhile, took over for an injured Bledsoe during the 2001 season and never relinquished the starting job. Brady went on to become one of the most decorated NFL quarterbacks in history: seven Super Bowls, a five-time Super Bowl most valuable player, a four-time league MVP, the all-time league leader in passing yards and touchdown passes. The accolades go on and on.

Bishop can’t help but wonder: Given the chance, would he have found the same success?

The NFL quarterback landscape is much different today than when Bishop entered the league. Now, his run-and-gun style dominates. Think Patrick Mahomes with the Kansas City Chiefs, a two-time Super Bowl champion. Jalen Hurts with the Philadelphia Eagles. Lamar Jackson with the Baltimore Ravens.

“A lot of people get excited about Mahomes and the throws that he makes. And I’m saying to myself, ‘I can make that throw to this day,’” Bishop says. “So if I could go back and get that opportunity…

“I see myself as a seven-time Super Bowl champion, four or five MVPs. I can see that because I believe in myself. And given the opportunity,” he pauses, “Every time I was getting an opportunity, I took advantage of it.”

On a cold winter’s day this past January, Bishop returned home to receive a package. Little did he know it would be one that would change his life. Bishop sat down on a Zoom call with Snyder, current Kansas State coach Chris Klieman, and athletic director Gene Taylor.

“We have called to visit with you,” Synder begins. “We all want to congratulate you. And we have the distinct honor of being able to share with you … that you have been selected to be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.”

Bishop beams at the news.

“I definitely appreciate it,” Bishop says. “I definitely, definitely am honored. I’m blessed. This is right up there with the Nebraska win, Coach. I’m so excited.”

“The impact you had on Kansas State, the impact you had on college football is being recognized,” Klieman tells him. “It’s so well deserved.”

“Like I said, and I’ll say this a thousand times more, I’m glad I was able to attend K-State and be a part of a great tradition, a great family, a great support staff and everything that came with it,” Bishop says. “I wouldn’t trade it for nothing in the world.”

Bishop will be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame this December in Las Vegas, where he’ll be enshrined with Snyder and three other Kansas State Wildcats among the all-time greats.

The day after the announcement, Bishop was back at the Legacy School of Sports Sciences, serving lunches and coaching players.

“If it was me and I just got inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame,” quipped principal Ralph Butler, “I would have taken a week-long vacation to celebrate.”

That was never a consideration for Bishop, who’s always carried a next-play mentality.

There’s a price to pay for greatness. Years of football are hard enough on a body, but even more for a quarterback who made a career out of running, scrambling, and taking hit after hit after hit.

In 2013, in Bishop’s last year in the CFL, he was healthy, in great shape, eating right. But one day he started sweating, his heart pounding. He started driving home but ended up at his sister’s house nearby, where he collapsed on the driveway. He suffered a stroke due to a blood clot behind his left ear.

At the hospital, he found he couldn’t move his left side. He was one of the youngest on the stroke floor. How could this have happened? Nurses rushed between rooms responding to code blues, an emergency alert that a person requires immediate medical attention or risk dying. Unaware of what it meant, Bishop joked with a nurse, “When am I going to get one of those?”

With two-and-a-half years in rehab, he learned to use his left side again. He still favors it slightly when he walks, but that’s the last inkling of his near-death experience.

He’s since returned to the football field, a leader teaching young men.

It’s a Friday night in Texas, the sun dipping below the grand bleachers underneath a purple-and-pink sky as his Titans storm the field at Falcon Stadium. His team may be from a rag-tag up-start charter school, but on this night, they’re proving why they shouldn’t be underestimated. They score early and fast. And halfway through the first half, the Titans leading 16-0, Bishop picks up on the Falcon quarterback’s cue that signals if they’re going to run or pass. Bishop is quick to relay the sign to his defensive coordinator. The Titans go on to build on their commanding lead and win, 29-0, retribution for last season’s opening loss.

Although much on this night went the Titans’ way, Bishop is quick to teach that life doesn’t always go according to plan—no matter how much you prepare.

“When it doesn’t, how do you respond?” he says. He’s thankful for his parents for these teachable moments, because it wasn’t long ago when he was held up in a hospital unsure of what he had left to give. “I’m still here for a reason, and that’s to be the best Mike I can be. Be the best leader I can be. Be the best competitor I can be. And I’m living my purpose. I’m seeing these kids do some great things here. And I’m proud of that.”

Check out Michael Bishop's segment in our 2023 television show.