Bomb sirens rang as Sanja Tomašević and her friends gathered near Lim River during a warm spring day in 1999. The 19-year-old Tomašević had grown accustomed to the singing sirens — a regular warning of the threats from the ongoing war that embattled Serbia.

In the war’s early days, Tomašević and her family would gather in a bomb shelter with enough food to last for days. Tomašević paid little mind to them on that day near the river, confident that whatever threat they warned of surely wouldn’t strike her small town. She huddled with her younger sister and friends around a broken wooden bench near the bank of the river.

That’s where she watched in “slow-motion” as a missile struck a bridge no more than two football fields away. The blast made her head “feel like it was going to explode” and sent her flying backwards onto the ground. Scraped and bruised, she grabbed her sister and ran home through the shattered glass that lined the streets. There, she hugged her tearful mother and promised to never again be so careless.

It wasn’t just the sirens Tomašević had grown accustomed to. Life in a war-stricken country came with its own perils. The value of the country’s currency was changing daily. Her town had electricity for only six hours each day, which limited her family’s food supply to mostly non-perishable items, such as flour, oil, and water.

She had one constant that kept her grounded, though: volleyball. She began playing at 9 years old at her father’s insistence. Her father ensured both she and her sister always had what they needed, especially when it came to volleyball. Something as little as having new shoes for games was a luxury — one they were always afforded.

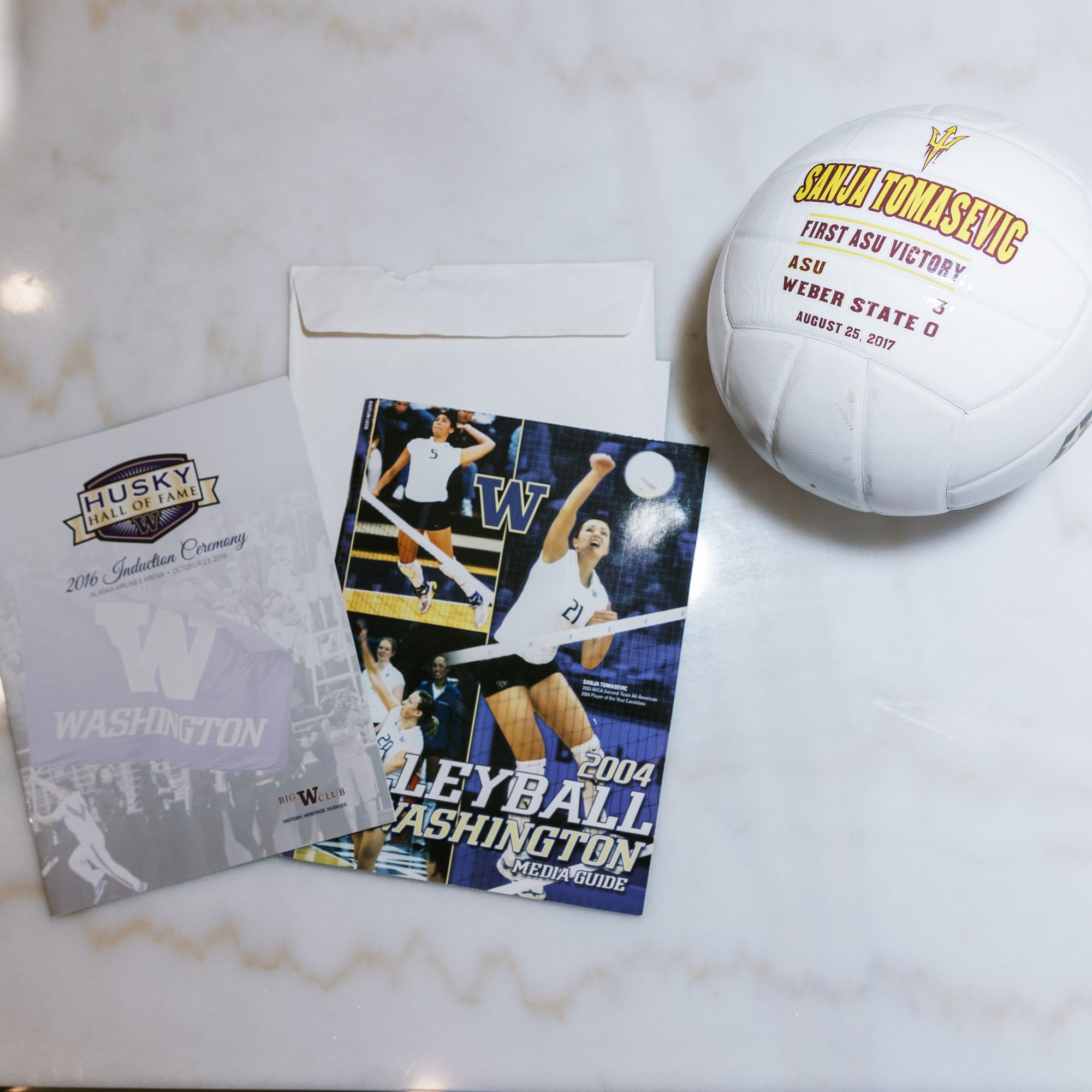

Tomašević was a ferocious outside hitter for the Huskies. [AP photos]

Tomašević fell in love with the game. She recorded videos of older players and obsessed over their every move, at times taping over family memories to her parent’s frustration.

“I watched so much it was almost unhealthy,” she said. “I could tell you what happened during every play in every match.”

By 19, she’d grown tall and lanky — a player who dominated as an outside hitter, but who also had the smarts to methodically dissect her opponents. She was recruited to play for Serbia’s senior national volleyball team, well on her way to becoming a fixture on the country’s Olympic squad.

Tomašević always had larger ambitions, though, that spanned far beyond her country’s borders. In Serbia, athletes must choose between a high-quality education or an elite athletic career. Tomašević wanted both. While recovering from a knee surgery, she sat alone in a hospital room, away from the cheering crowds and media spotlight that surrounded so many of her games. She was lonely and realized she was only as valuable as her body and volleyball skills carried her.

Against her team’s wishes, Tomašević left Serbia in 2002 to join the University of Washington volleyball team. She knew little English and had few friends, but she wanted to prove to herself that she could succeed.

“If she sets her mind to it, she’ll do it,” said Danka Danicic, her close friend and teammate at Washington. “She’s very ambitious and confident in her abilities.”

Before she left, Tomašević had a conversation with her dad, who told her: “With all these obstacles, you have persevered and pushed through to go live your dream,” she recalled. “I wouldn’t be surprised if you end up at the White House.”

At Washington, Tomašević learned the rumors about American volleyball weren’t true — she could play at an elite level while receiving a quality education. During her four years, she helped build the Washington program into a powerhouse — while studying for a degree in communication — culminating in a national championship her senior season.

Jim McLaughlin recruited Tomašević to the University of Washington and watched her develop into one of the best players in the nation.

“She has the characteristics of a champion,” McLaughlin said. “Her commitment level. Her perseverance. Her concentration, focus and energy. She was one of those players when a situation called for her to be her best, she rose to the occasion.”

Three years after college — while playing professionally in Europe — Tomašević was recruited to play for the Serbian national volleyball team. The team had lost its two outside hitters to injury while attempting to qualify for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Tomašević stepped in and helped Serbia beat Poland in a five-set match to secure her country’s first Olympic berth in volleyball.

She was ecstatic, but she was left with a difficult decision. Her coach wouldn’t guarantee her spot on the roster with the team’s injured outside hitters expected back before the Olympics. Tomašević was also applying to get her green card to become a permanent resident of the U.S. She was advised that if she trained with the Olympic team — spending months overseas — her green card application could be put in jeopardy.

“As an athlete, it’s a dream to go to the Olympics. But when you’re put in a position like I was, it’s a tough decision. Do I train for the Olympics and hopefully make the team? What if I don’t?” she said. “And if I’m training, I’m jeopardizing getting my green card. What if I don’t make the Olympic team and then I don’t get my green card? That would be devastating.

“I asked my parents, my friends, my coaches — I asked everybody about it. I wanted someone to make that decision for me.”

Ultimately, she chose her green card.

“I felt like that was the safest route to go,” she said. “I wanted to live in the United States. I wanted to raise a family in the United States.”

Tomašević, with daughter Stella, at home near Phoenix, AZ. [Stephanie Ringleb photos]

Tomašević spent four more years playing professionally. Eventually, the years of constant travel and instability grew too much, but she wasn’t ready to give up the game. She accepted a coaching job with the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Now 42, she recently agreed to part ways from the Arizona State University volleyball team, where she coached for the past six seasons. She’s going to take time away from volleyball, uncertain what that exactly entails after so many years where the sport dominated her every decision. She plans to spend more time with her 5-year-old daughter, Stella, and enjoy weekends with family and friends.

Regardless of the future, she’s thankful for the sport that brought her to America, one that allowed her to travel the world, and for her parents who introduced her to the game that would change her life.

After winning the national championship with the University of Washington, her team traveled to Washington D.C. for a congratulatory meeting with President George W. Bush. Before she stepped inside, she made a quick phone call.

“Guess where I am right now,” she told her dad. “I’m about to walk into the White House.”

From her days with the Serbian national team to the White House as a national champion with the University of Washington Huskies. [Sanja Tomašević photos]