The wheels of the old gray Pontiac moved slowly as Tanard Davis inched his way through traffic. His heart was beating, mind racing, and paranoia settling in as he navigated the back roads of Coconut Grove.

Then a 17-year-old high school senior, Davis needed a quick $1,000 for prom. His job at McDonald’s wasn’t enough, so he turned to a cousin who was a well-known drug dealer in Miami. Would he help him with the money, Davis asked? Only if Davis agreed to deliver a package of marijuana, his cousin told him. Desperate for the cash, Davis agreed.

“I didn’t ask questions,” Davis recalls today. “I just needed to make the money.”

Looking back 22 years later, Davis knows the decision could have changed his life. Had he been caught, gone would be the days of playing college football. There would be no flashy Super Bowl ring emblazoned with the Indianapolis Colts’ blue horseshoe. There never would have been a resurgence of his athletic career as one of the United States’ premier ja alai players.

Davis avoided the traffic-filled interstate and drove slowly through the streets, where it seemed like he passed a police car at every comer. He worried the marijuana smell would seep out of the trunk and raise suspicion. Was the quarter tank of gas enough to get him to his destination? What if he was jumped and beaten once he arrived?

After a 40-minute drive — one that felt like hours — Davis arrived, dropped off the package, and got the money he needed for prom. The experience left him so traumatized that he swore he would never do anything so reckless again.

“It was the scariest moment of my life,” Davis says. “At that moment, I told myself I would never get into that life.”

Davis grew up in the inner city of Miami in the 1980s and ‘90s, where drugs — namely crack — ran rampant in the streets. He grew up in a single-family home, where his mom used drugs. His father wasn’t around. Davis watched as his friends got lost in a life of selling drugs and pulling in quick money.

Davis wanted more out of life. Rather than drugs, he turned to sports — namely football and track. He developed into one of the fastest high school athletes in Miami-Dade County and drew interest from some colleges, but his off-the-field behavior limited his scholarship offers.

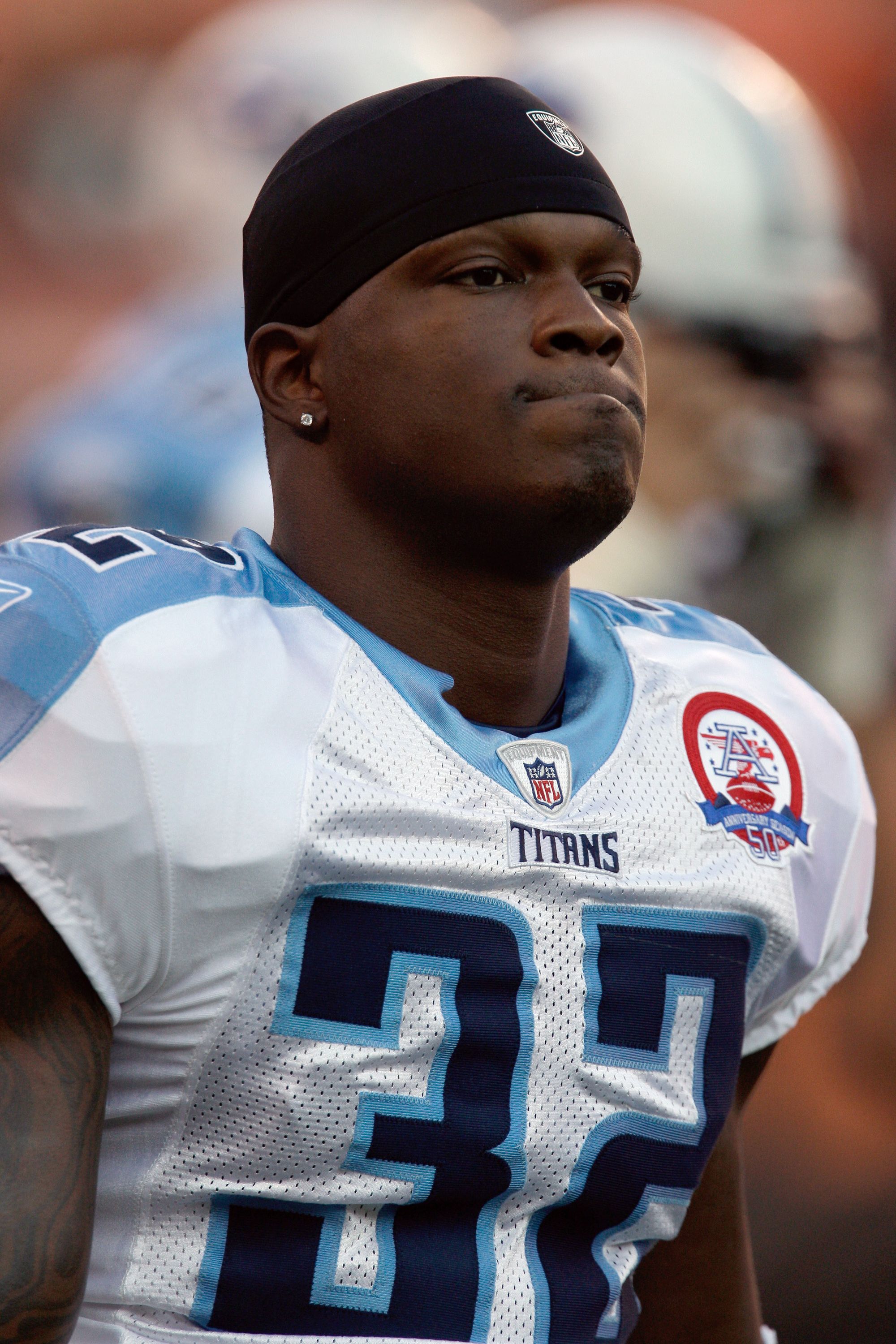

Tanard Davis bounced around the NFL. He found a job in law enforcement before jai alai found him. [AP photos]

“I had an attitude and I was pretty immature at the time,” Davis said. “I got into a lot of fights in high school. I had a lot of insecurities and low self-esteem.”

He accepted a football scholarship to Saint Peter’s University in New Jersey for one season before transferring his sophomore year to the University of Miami on a track scholarship. As a junior, he won the Big East 60-meter championship. Impressed by his speed, then-head football coach Larry Coker gave Davis a spot on the football team as a walk-on. But, Davis said, his immaturity and low self-esteem held him back from regularly starting.

After his senior year, he received some interest from NFL teams, but his name went uncalled on draft day. With $27 left in his bank account, he was left to decide if he wanted to pursue his NFL dream or join the Army. That’s when he received a call from Tony Dungy, head coach of the Indianapolis Colts.

“He said, ‘Tanard, we’re excited to have you. We would love for you to try out for the team, but we want you to make the decision that’s best for your family,’” Davis recalls Dungy telling him. “No other head coaches called me. I felt like Tony Dungy really wanted me there, so I went with the Colts.”

Although Davis didn’t make the Colts’ active roster, he signed with the team’s practice squad the same year they won Super Bowl XLI. Davis said it was surreal walking the streets of Miami — some of the same streets he walked growing up — soaking in the full Super Bowl experience in his hometown.

But Davis had bigger ambitions still. He wanted to be on a team’s active roster and on the field when the Super Bowl clock struck zero. He was cut by the Colts after the season and bounced around the league for the next two years, never achieving that Super Bowl glory.

Tanard Davis has risen to the top for Magic City Casino. [PJ Davis photos]

Davis thought his professional athlete days were over. He decided to pursue his other dream of being a police officer and joined a force in Atlanta.

“I wanted to be a difference-maker in the community. I wanted to be a direct line to kids who are looking for a way out and trying to get advice from somebody who can relate to their situation,” Davis says.

He also dabbled in acting, starring in independent films and TV shows. He made appearances in the movies “Ant Man,” “Selma,” and “All Eyez on Me,” the biopic about iconic rapper Tupac Shakur.

Back home in Florida, Magic City Casino had its sights on Davis. The casino was replacing greyhound racing with jai alai, a fast-action sport that was popular in the U.S. through the 1980s before it fell out of fame because of corruption and drugs.

Jai alai (pronounced HIGH-LIE) is known as the fastest sport in the world. It involves players using a cesta, or curved wicker basket, throwing a hard ball known as a pelota at speeds upwards of 130 mph on a three-walled fronton, or court.

The sport was founded some four centuries ago in Spain before the first fronton in America was opened at the 1904 World Fair in St. Louis. In its heyday in the ‘70s and ‘80s, crowds of 10,000 or more would fill the stands in Miami to watch and bet on matches. But the sport began to fall out of favor in the late 1980s due to corruption, drugs, and the rise of other professional sports like baseball and basketball. Fans also had an easier gambling outlet with the creation of the Florida lottery in 1988, which coincided with a player strike that lasted more than two years. All told, jai alai was pushed to near extinction in the U.S.

That is until 2017 when officials with Magic City Casino set out to revive it.

“We’re pretty confident there’s a future,” says Magic City’s Scott Savin. “At least there’s a present, so that means we have a fighting chance at a future.”

While filming for a TV show, Davis received an email asking if he’d be willing to try out for the team. The owners of Magic City, who are donors to the University of Miami, asked the athletic department to send an email to all former athletes asking if they’d be willing to try out.

“If you have the ‘U’ heart, the drive to compete, the strong legs and arms to excel in the arena, stay on the look-out for the tryout schedule,” the email read. “Upon successful selection, ‘U’ will be trained for six months, with the first competitive games scheduled to play in July 2018. We look forward to ‘U’ joining our ‘family first’ of athletes.”

At first, Davis ignored it. Then he received a personal email from Savin welcoming him back to Miami for a tryout — all expenses paid. What did he have to lose, Davis thought. When he stepped on the fronton and strapped the cesta to his hand, Davis fell in love with the sport.

“Jai alai is a sport where respect is needed,” Davis says. “You put your hand in a basket and your hand is flat. You can’t grab anything. You have to develop your tendons and your muscles and your wrists and your elbow to find a release from the ball, just like you’re throwing a baseball.

“The beauty of the sport is you don’t have to be the strongest or the fastest. You have to be the most technically sound and your posture needs to be polished in order to be an effective player.”

Davis and 17 others signed a contract with Magic City Casino and were given seven months to train from novices who barely knew anything about jai alai to competent players who could star for the casino.

Tanard Davis poses at the Magic City Casino fronton. [PJ Davis photos]

“This is not a game that you start playing in your 30s or 40s,” coach Juan “JR” Arraste says in the movie “Magic City Hustle,” a documentary that followed Magic City’s first jai alai season. “This is a game you start to play as a kid. It’s a difficult game to learn.”

While coaches raved that the players had made great progress in those seven months, Davis said the opening performance was one of the “worst day opener for any sport I’ve seen of any kind in U.S. history.”

Fans jeered and heckled the players as they missed the fast-moving pelota and made errant throws with their cestas.

“A lot of the fans who are diehard jai alai fans were extremely upset,” Davis says.

Davis took it personally and trained harder, ultimately rising to one of the sport’s premier athletes in the U.S. by the season’s end. After leaving the NFL, Davis never thought he’d find himself back as a professional athlete and he’s thankful for all that jai alai has given him these past six years.

He’s unsure how much longer he’ll play. At 40, Davis is more reflective these days, cherishing the memories he’s made throughout his life and all that sports has given him. A Super Bowl ring. A love for jai alai. A life beyond the drug-filled neighborhood where he grew up.

“I’m all about the butterfly effect,” Davis says. “I don’t want anything in the course of my life to change differently. I love the way my life turned out to be.”

He paused.

“If I changed it, I don’t know what kind of person I would be today.”