It’s 3:47 p.m. on a Wednesday in early August and Will Francis is driving from one twin city to the other. The Anaheim Ducks draft pick has a couple of stops before his day is done.

When I asked where he’s headed, he unintentionally left out the first destination. Probably because he’s more excited about the second one.

“I’m just heading over to the other side of town to go muskie fishing with one of my buddies, actually,” he says. In the background, semi trucks grumbled past while the din of traffic and the brown noise of the car cabin provide the soundtrack for our call.

Being a former Minnesota resident, I chime in with, “That’s such a Minnesota thing.”

He laughs in agreement. If you know, you know.

Over the next 45 minutes, as he navigated the concrete veins coursing through Minneapolis and Saint Paul, eventually terminating his journey at Wayzata Bay for an evening angling session on the cold blue waters of stately Lake Minnetonka, he took me through the important chapters in his life that included his dad casually suggesting he could be an NFL punter and his commitment to the University of Minnesota-Duluth as a defenseman.

Either of those would be a good foundation for this story. But to understand Will Francis the athlete, you need to understand what happened to Will Francis the person when he went on a trip in March of 2020 and found himself inside the steel shell of an ambulance on a four-hour journey to a children’s hospital.

Francis was born in the small town of Lino Lakes, just north of Saint Paul. He later immersed himself in every sport and outdoor activity he could fit under the waning daylight of those heavy, moist Minnesota summers and lung-searing, frigid winters.

The athlete gene runs strong in his family. His father, Jeff, played a year of college football at North Dakota State before transferring to the University of Minnesota to focus on a degree in chemical engineering. His grandfather — also named William Francis — played college hockey and baseball, and won a high school state championship in hockey in the 1960s.

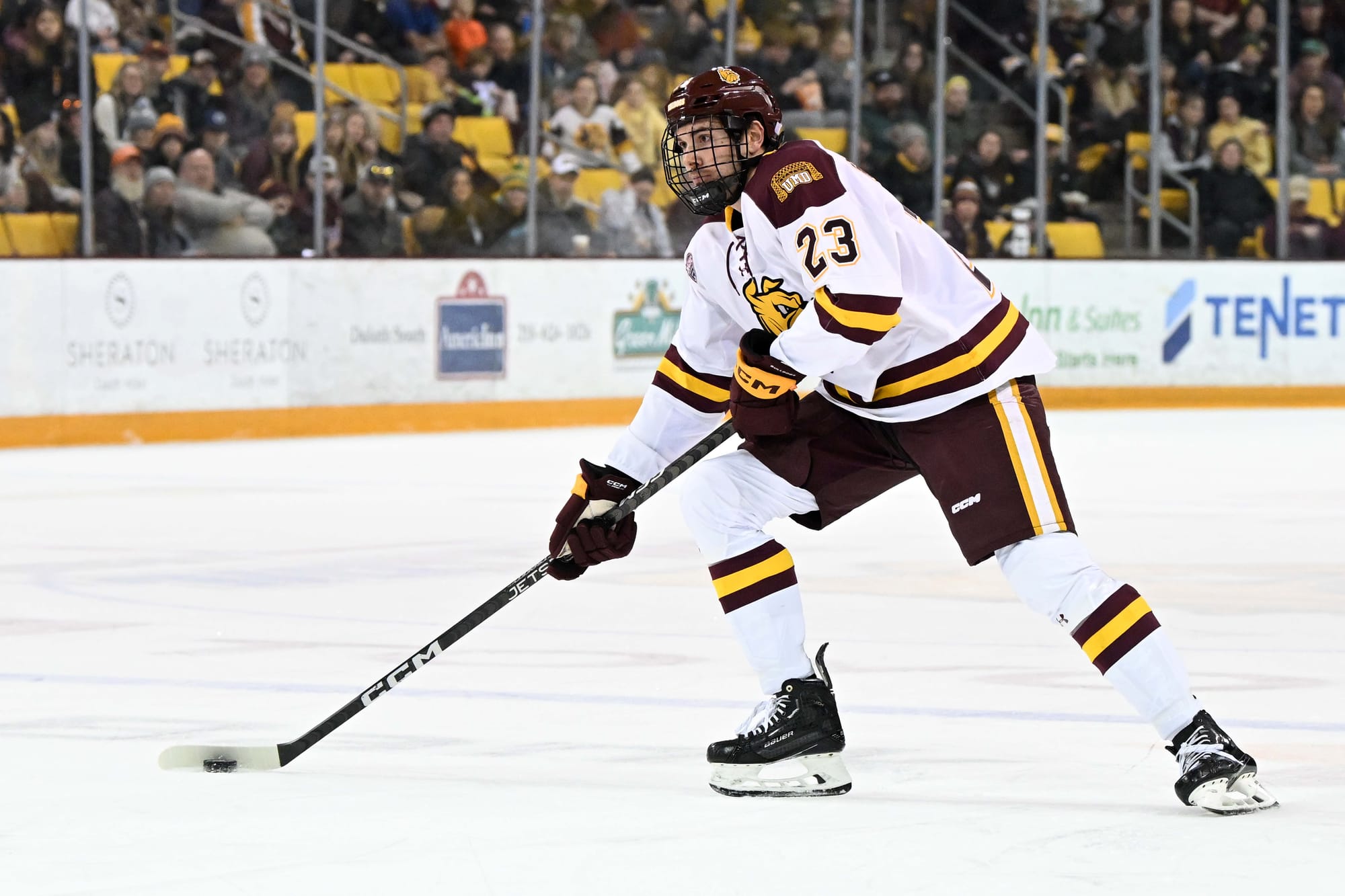

Things were looking up for Francis when he was drafted in the NHL's sixth round by the Anaheim Ducks. [Photos courtesy UMD]

Francis took a liking to football, baseball and hockey. He also discovered a love for the lake life — the natural Minnesota state of mind — where fishing and waterskiing and wakeboarding and ice fishing and snowmobiling across those vast, liquid-turned-frozen playgrounds proved exhilarating and rewarding.

“I was just always on the go. I was playing three sports up until high school, when I dropped baseball and played high school golf.”

Slowing his roll, I inquired about his positional fortitude in each sport. Not surprisingly, the list is long.

In football?

“I was kind of a combo not seen too often with quarterback and defensive end, playing both ways just because of my size. Then, when I got to high school, I played wide receiver and then somehow I was always just good at punting for some reason, ever since I was a little kid.”

He shared a story about a teammate who, in a tight game against a district opponent, dropped the snap in the end zone while attempting a punt. The other team recovered for a touchdown, and Francis quickly found himself assigned the punting duties.

“They threw me in there the same game and we were on our own goal and I had a 75-yard punt from our goal. And somehow, ended up finishing the year (as the punter). I ended up with a school record for punting average, which I had absolutely no idea about.”

Around this same time, he’s getting interest from some Division I colleges for hockey and is exploring options in the USHL when his dad — mostly teasing — wonders, Why are you wasting your time playing hockey? You have a gift, you could be an NFL punter someday.

“So it’s kind of become a running joke,” Francis says, before casually slipping into the conversation he also played some at linebacker.

Eventually, hockey edged its way in front of the other sports he loved. It helped that Francis had a growth spurt in high school — from 5-feet-10 to 6-feet-4.

“The growth spurt jump-started me filling into my frame. Once I got to my junior year, I definitely started to put myself on the map to break out and apart from the rest of the group.”

His junior season at Centennial High School was memorable in that the squad qualified for the famed Minnesota state high school tournament at the Excel Center in Saint Paul. Although they didn’t bring home the championship, Francis was able to appreciate the mega-event in a similar way his grandfather did decades prior.

The team graduated 13 seniors that season, and the following year Francis would be the lone rising senior. The program was reloading, and in that critical final year of high school he needed something more to keep himself on the radar.

“It was going to be a lot tougher year, just from a standpoint of what we had coming back. And I also just wanted to be in a place where everybody had the same goal of playing at the next level.

“My senior year I went down to Cedar Rapids (USHL), which was a great experience for me at 17. It was like — and for the first time — I didn't feel comfortable. It was the right move for me, for what I wanted to accomplish.”

In October of 2018, Francis committed to the University of Minnesota-Duluth. They were one of the first schools to show interest in the young defenseman who was growing into a prototypical NHL-coveted two-way player. While most of his extended family had attended the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, Francis never felt the same lure despite the family having season tickets for football and attending many hockey games on campus.

“It was never somewhere that kind of called my name,” he says.

But Duluth did.

“My parents had a cabin up on the north shore. So I was just familiar with Duluth as a middle ground. I just always wanted the city and then once I got to see everything with the facilities and the rink, and just the town in general … it was kind of a no-brainer for me once they started to put an offer out for me to come there.”

Early in his second season in Cedar Rapids, Francis suffered a knee injury in practice that would end his season. He was on crutches and decided to head home for surgery and rehab. It was November and an early snow storm inched its way across the plains and upper Midwest. Things like this don’t phase those raised in Minnesota.

“I packed my whole car up and drove like six hours through that snowstorm just to get home to have that surgery.

“So I'm rehabbing this injury. I'm not skating, not doing a ton of cardio. And then I'd just notice, like I was still in a straight brace and kind of taking it easy with my knee. But I just noticed whenever I hobbled up the stairs, I always felt lightheaded at the top and sometimes that happens, right?”

This was his first clue that something wasn’t right.

“It was just so consistent. Like every single time, I’d get to the top of these stairs and have a heartbeat in the back of my head, like kind of a slight pulsing there, and I could feel it around the back of my head.”

While he was rehabbing his surgically repaired knee, Francis continued to work on his upper body strength in the weight room. What stood out quickly was the progress he wasn’t making.

“On my bench and pull-ups, like the weights and the reps that were easy to do a month ago now are just really, really hard. And then I was just starting to feel like run down, and I thought it was actually like a conditioning issue. So I ended up by bringing a stationary bike into a sauna one day, thinking I was out of shape and just rolled it inside the sauna and just felt terrible afterwards.

“I was sick, but I had no idea at the time.”

Concerned, Francis went to see a doctor. Twice. The first one said he had a “virus” and it was “nothing to worry about.” Resting at home, his condition wasn’t improving, and now he had a bad sore throat. This time, antibiotics cured his throat, but his general malaise persisted.

“I was tired all the time,” Francis says.

New symptoms crept to the fore, signaling that something more nefarious was lurking inside his body. Deep down, he knew something was … off.

“I ended up going to the state hockey tournament with some of my friends and we had seats close down by the glass and I walked up the stairs and we got to the top and I just blacked out. I was like, ‘Hey, guys, give me a second. I can’t see.”

I can’t see.

Francis regained his vision in short order and said he felt fine the rest of the evening, with no obvious symptoms. Later that week, it was Spring Break and he had plans to vacation at a family cabin near the Canadian border. His dad, a couple of cousins and his uncle were all on the trip.

Early in the trip, they went on a snowmobile adventure. He then slept for almost an entire day.

“That was not like me. I’m always on the go, always energetic. And now I had no energy.”

His dad decided to take him to the local hospital to get some tests done. Francis says the date was March 13, 2020. The day the world shut down from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“And the first thing the doctor says is, ‘Don’t be bringing that Covid stuff in here.’”

After a battery of tests, Covid wasn’t the thing they were worried about. As Francis sat in the room with his dad, the doctor came back in street clothes. This caught his attention.

“I had to get my head right when that happened. I’m like, ‘Either something here is totally fine or something is really wrong.’”

The doctor started giving a long-winded version of the tests they completed and the things they ruled out before an anxious Francis cut him off.

“Just tell me what’s going on straight up.”

He explained that his white blood cell count was 178,000. It should be closer to 10,000. And then, in the paleness and sterility and vulnerability of an exam room, the doctor delivered the blow the Francis family wasn’t expecting.

“You have all these signs pointing toward leukemia.”

Soon, he would be in the back of that ambulance on the four-hour journey to the University of Minnesota Children’s Hospital. His meteoric rise from Centennial High School to Cedar Rapids in the USHL to Anaheim Ducks draft pick in the NHL and soon-to-be freshman at Minnesota-Duluth all took a back seat to this most urgent battle for his health — if not his life.

As Francis put it, “Eight months ago I was drafted to the NHL and now I’m diagnosed with cancer at 19 years old when you just felt like you’re on top of the world.”

Further tests confirmed the diagnosis and within days, he was on chemotherapy. He would undergo five phases of treatment over the next two-and-a-half years.

“The first month was super intense,” he says.

In the fall of 2021, he was enrolled at Minnesota-Duluth. He took classes. He practiced. He took chemo pills. Every day. Through all of it, he managed to play in five games.

“I got better as time went on. I thought I was playing well my freshman year, but I also felt like I was taking three steps forward and one step back through the treatments.”

Eventually, time became his consoler and his friend. In his sophomore season Francis played in 28 games. He was starting to feel like his old self. In the summer of ’23, he declared he was in the best shape of his life. He was working out with college and NHL players at a local training facility, and on merit alone, he was in a group with NHL defenseman Ryan McDonagh, a two-time Stanley Cup champion and former Mr. Hockey of the state of Minnesota. McDonagh is a rugged, two-way player. And Francis saw a future version of himself in the former Wisconsin Badger.

“They had my workout pretty much the same as his. The same weight, same reps, same rest.” All of this was promising and exciting.

At this point, he’s getting his blood work vetted every two months. In early August of ’23 he went in for one of these routine tests on a Friday. On Monday he learned he had relapsed.

His world stopped. He was in shock. He made tearful phone calls to his family, his friends, his coaches, and the player development staff of the Anaheim Ducks. He began treatment right away, choosing to redshirt his junior year at Minnesota-Duluth to focus on getting healthy and kicking leukemia to the curb once and for all.

Francis was receiving treatment on the daily while staying in the hospital from mid-August to mid-September — 29 days, he recalls. He was feeling good, getting some light exercise and going on walks. But he’s itching to return to the ice. This is when he and his dad hatched a plan.

With the University of Minnesota being essentially across the street from the hospital, his dad called a friend who helped reserve an ice rental at Ridder Arena, the women’s rink on campus. For two weeks, Francis would tell hospital staff his dad was picking him up to grab a breakfast sandwich. Instead, they would wheel over to the rink and skate for an hour each morning.

“It put me in a good headspace. It just felt natural and I wasn’t locked up in a hospital room.”

By November, he had beaten back the disease once more. In January of ’24, he played in an exhibition game against the University of St. Thomas. He remembers receiving stick taps from the opposition during warmups, a sign of respect and something he remains grateful for to this day.

There would be more tests, biopsies, bloodwork. Another relapse was a real possibility.

As he recalled his journey with great detail, he offered a new wrinkle and shared something few people knew: On April 19th of this year, he had a bone marrow transplant. His brother Luke was a 100% match and became his donor. Francis recently had a Day 100 bone marrow biopsy, and the report was good. His blood and marrow cells were 100% his brother’s, and there’s no detectable disease.

“So I kind of got back into the gym and skating, the week before the Fourth of July and then just catching up to hopefully be ready in October of this year. It's my goal to be ready game one at UAB (University of Alabama-Birmingham) my senior year.”

As our conversation skidded toward its conclusion, he revealed the first unspoken destination for that evening. He had just pulled into Braemar Arena in the suburb of Edina, where he was about to play in the popular Da’ Beauty League, a summer showcase where professional and college players compete to stay in shape and keep their skills sharp.

Before he bid farewell and slipped out of the car and into the humid summer air, he shared the story of his NHL draft day. His whole family attended the event in Vancouver, British Columbia. He wasn’t sure where he’d land — Francis had no gut feeling on what round or which team. The Ducks took him in the sixth round and an emotional Francis was elated, celebrating with his family that night with a nice dinner before heading to development camp. A dream fulfilled.

So I asked him if his dad — having just seen his son drafted into the world’s best league — let go of the NFL punter dreams.

He laughed and added, “He still jokes about it to this day. He’s like, ‘You should just walk out there with UMD’s football team and see if you can just kick a couple.’ He jokes that it’s my true skill.”